Superman’s cinematic design has mirrored shifting cultural moods: Reeve’s bright sincerity, Routh’s nostalgic sepia, Cavill’s armored pessimism, and Gunn’s saturated reconstruction. Each iteration retools color, texture, and sound to test how much hope audiences can bear. This brief traces these design choices against their historical and artistic contexts.

Superman on film has always functioned less as a single character than as a recurring design problem: how to render an archetype that is, at once, too simple to be modern and too important to abandon. Each cinematic era has addressed the problem by adjusting its palette of color, texture, and sound in response to the prevailing cultural mood. What emerges over the decades is not merely a sequence of costume changes and score revisions, but a conversation between America’s collective emotional register and the representational apparatuses of blockbuster cinema.

Sloptraptions is an AI-assisted opt-in section of the Contraptions Newsletter. Recipe at end. If you only want my hand-crafted writing, you can unsubscribe from this section.

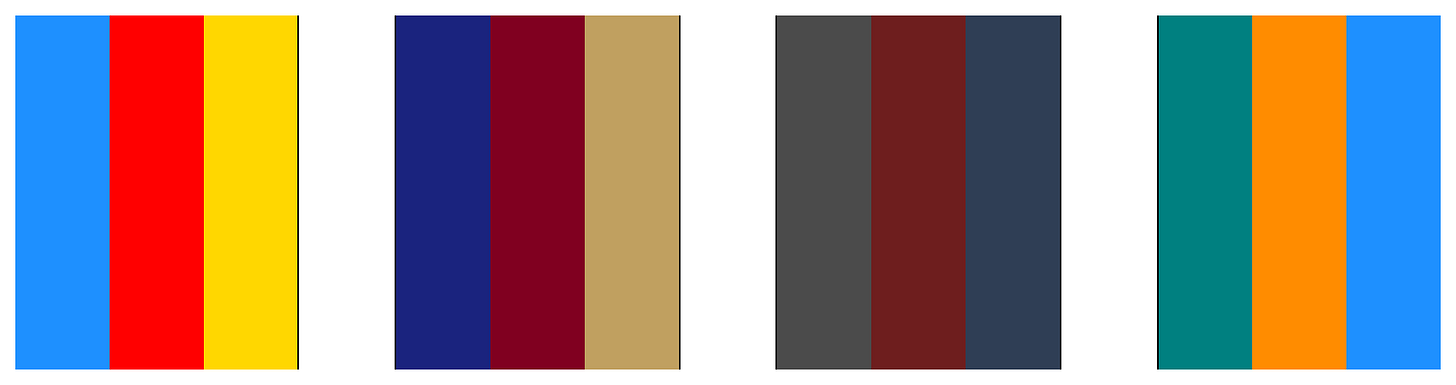

The Reeve era began in 1978 with Richard Donner and John Williams, and it carried the scent of an exhausted decade searching for sincerity. The visual design was strikingly literal: spandex primary colors that matched the newsstand comic book without apology, filmed in bright natural light. Williams’ orchestral fanfare—the definition of a melodic hook—soared above it, making sincerity feel not childish but mythic. In an era marked by post-Watergate distrust and economic stagnation, this Superman worked because it contrasted with the zeitgeist. The design stood as a tonic, offering a reassuring fantasy of incorruptible virtue staged in earnest rather than with irony.

Bryan Singer’s Superman Returns in 2006 tried to sustain that aura by way of homage. The design strategy was sepia-toned nostalgia: colors muted into burgundy and navy, the texture rubberized to suggest seriousness without actually innovating, and John Ottman’s score carefully re-orchestrating Williams’ themes. The mood it constructed was elegiac, more a shrine to the memory of hope than a new articulation of it. This was an odd fit for the moment. The mid-2000s cinematic audience was drifting toward reinvention and grit, carried along by Nolan’s recalibration of Batman and by Marvel’s imminent tonal confidence. Singer’s Superman, then, read as backward-looking. Artistically, it achieved a certain reverent competence, but it failed to resonate because it staged the icon as artifact rather than as living myth.

Zack Snyder’s reimagining with Henry Cavill in Man of Steel (2013) pivoted hard away from nostalgia. Here the design strategy was deconstructive. The suit became alien chain-mail, darker and embossed, stripping away softness in favor of power. The cinematography drained color, leaving a palette of gray-greens and leaden skies. Hans Zimmer’s score abandoned melody in favor of rhythmic ostinatos and heavy percussion, trading Williams’ brass fanfares for something primal and forceful. This design language reflected the early 2010s mood: a world of financial crisis hangover, wars without end, and growing political fracture. Superman was recast not as a bright savior but as an alien god whose very presence was unsettling. It worked as a work of auteurist worldbuilding, but it remained divisive. The heaviness fit the pessimistic zeitgeist but sat uneasily with a character whose essence is brightness. It produced awe but little warmth, resonance for some but estrangement for others.

James Gunn’s Superman pushes back toward brightness, though not naively. The film leans into saturated color and a cleaner suit design, deliberately rejecting Snyder’s desaturated gravitas. John Murphy and David Fleming’s score quotes Williams while layering in Gunn’s familiar pop-inflected orchestral idiom. Critics have called the result colorful, heartfelt, and occasionally chaotic, praising its energy while noting its clutter. Artistically it largely succeeds as a reconstruction: sincere without being innocent, designed to reassert Superman’s relevance by restaging hope for a weary, irony-saturated audience.

Across these eras the character is less a fixed icon than a cultural barometer. He has been staged as tonic, relic, alien burden, and reconstruction—each time a different answer to the same design brief: how much sincerity can the moment bear, and in what form will it be believed?

Recipe

Here is the chat transcript

We followed a layered design-review protocol. First, we built descriptive scaffolding by comparing palettes, textures, and soundtracks across the four Superman eras. Next, we reframed those observations as cultural interpretations, aligning each aesthetic with its zeitgeist and assessing artistic effectiveness. We then compressed this analysis into abstract and summary forms, iteratively refining tone and density. Finally, we produced companion visuals—2×2 diagrams and color swatches—to anchor the argument, and packaged the whole into a markdown brief with a unifying title. The process balanced descriptive detail, interpretive synthesis, and visual accompaniment in successive passes, moving from raw analysis toward a polished, self-contained artifact.