Beyond Szabo Scaling

Miniaturization and orchestration of human capabilities with AI and protocols

A question has been nagging at me over the last week or two, as I’ve been heads down preparing to run the week-long Protocol Symposium: What exactly is the problem we’re trying to solve? (where we is the several-hundred-strong emerging protocols scene the event is for).

While I’m more willing than most to spend multiple years nerding out over an idea for its own sake (and protocols present endlessly interesting nerd-out dimensions), I’m not enough of a philosopher to ignore real-world relevance indefinitely. Plus the Summer of Protocols is not just a self-indulgent idea startup (which is how I view my writing life for instance), but a program that runs on Other People’s Money™ that comes with expectations of broader societal value eventually emerging.

I’ve been running the program for 3 years now, and it’s achieved a certain precarious maturity and research-zeitgeist fit (RZF). So it’s time to ask the question: What exactly is the problem we’re trying to solve?

And since it’s an open, public-interest program, I want to try and work out the answer in public. I’ve gestured vaguely in recent posts about “cosmopolitanism” having something to do with it, but what exactly?

A good pointer to the answer, if not the answer itself, is the phrase social scalability.

Trust-Minimizing Scaling

In the crypto world, which both funds and philosophically inspires the Summer of Protocols program, the phrase points to the first (and in some ways, only) answer, articulated by Nick Szabo: social scaling being effectively reducible to trust-minimized scaling.

While there are other answers (or views that can be cast as answers) in the social sciences and humanities (Pierre Bourdieu’s sociological theories among them), they don’t directly grapple with social scalability as a normative rather than descriptive concern, with an eye to imagining and engineering novel approaches to scaling based on new technologies.

Trust-minimized scaling can be described as the following strategy: Solve every problem, at every scale, with the minimal mutual trust required among participants for success.

Early in the crypto story, circa 2009-13, there was a lot of talk of trustless architectures, but there has since been a growing appreciation that that’s too strong a term, and not even imaginable in principle, let alone practice. So phrases like “trust-minimizing” and “sufficiently decentralized” are the staples of crypto discourse in 2025. But though the views have gotten more nuanced, the fundamental tendency is still towards designing for a default assumption of not just low trust, but active distrust. The crypto world is built on red-team thinking. The “Dark Forest” metaphor is popular.

If you lack intuitions around this conversation, here is a simple way to appreciate the posture. The “crypto way” is to try and solve every problem with the least expressive computer (loosely construed, comprising both human and machine elements, and encompassing embodiments like markets and bureaucracies) that will do the job.

Examples of such minimally expressive “computers” include traditional markets mediated by token-based prices, and Bitcoin itself, which deliberately eschews a Turing-complete design based on trust-minimization. One of the spiritual conflicts between Bitcoin and Ethereum is that the latter has chosen to embrace Turing completeness in the vision of a “world computer.” It is, for trust-minimizing social scalers, too expressive. Bitcoin maximalists are trust minimalists. Ethereum partisans are willing to trade off some trust minimality for… other things.

While trust is certainly an important variable, Szabo’s account of social scaling feels at once too broad and too narrow. Trust is just one element, but it also an extraordinarily profound and foundational element, making it possible to reduce every other consideration to trust if you’re inclined to do so. And sometimes this is the right thing to do. One of the short courses in our upcoming symposium is on trust-experience design.

Trust is like time in that sense; what statisticians call a “fertile” variable that can be made the independent variable for almost everything else. Talk of “trust” in 2025 spans a range from speculation about quantum-resistant cryptography to how nation states can create more legitimate forms of voting.

Szabo’s account also focuses on blockchains in part because they offer a great deal of expressivity when it comes to modeling and synthesizing trust experiences, without requiring opening up too much expressivity along other dimensions of experience. It is honestly quite amazing that you don’t need Turing-completeness to construct a machine as weird as Bitcoin.

When you’ve got a hammer blockchain in your hand everything looks like a nail trust problem. Especially if that blockchain is the Bitcoin blockchain.

Today, 16 years after the invention of Bitcoin, the crypto world is guardedly exploring a range of positions on the spectrum between trust-minimizing and more expressive social scaling architectures. Ethereum occupies something of a middling position. Solana explores greater expressivity, not by increasing computational leverage (you can’t do much more after going Turing-complete) but by loosening the sociopolitical architecture constraints around the blockchain (around where physical computers validating the blockchain can live for example).

Most recently, the booming world of stablecoins loosens constraints around social trust minimization even further. To use a stablecoin, you must bring back the dreaded nemesis of Szabo, the “trusted third party,” in the form of entities like the US government (for dollar-pegged stablecoins) or Stripe (the corporation behind the new Tempo blockchain, no relation). As more state-sponsored stablecoins (so-called central-bank digital currencies, CBDCs) come online, the picture will only get more complex.

While all this fleshing out of the positions on the spectrum is good, and I’m glad the blockchain world (and the adjacent architectural spaces that use many of the building blocks of blockchains without being blockchains) is going beyond trust-minimizing scaling, the larger problem is seeing everything through the lens of trust (and therefore, blockchain-like or blockchain-adjacent infrastructures), even if you don’t seek to minimize trust.

Social scalability is about more than trust-experience engineering.

The focus on trust minimization (which, to repeat, is an important consideration, but far from the only consideration or even the most important consideration in every case) in what I’ll call Szabo scaling reflects a fundamentally pessimistic view of human sociality itself.

Expressivity-Maximizing Scaling

So while I do think social scalability is the pointer to the answer to “what problem are we trying to solve here?” Szabo’s answer leaves me more than a little underwhelmed. I don’t want to live in a bleak future where everything above a libertarian threshold of trust is reduced to a tokenized matrix of trust-minimizing protocols, and Ayn Randian heroes bestride the world like little Dunbar-scale collossi.

Can we do better? To explore the question, we must first decide what it is we’re scaling, and more precisely, what legible figure of merit we are maximizing or minimizing. Libertarians are typically terrified that the only alternative answer is some version of Borg-like communism, which is about scaling “equality” in some sense. But there are a great many more possibilities.

I propose societal expressivity as the right quantity to try and maximize. Loosely, for every problem at every level, build the most capable global computer (human + machines) we reasonably can, leaving a lot of surplus expressivity and power to work with. What’s more: This is in fact what we’ve actually been doing for 200 years, overbuilding societal “computers.”

What do we do with that surplus? We fuck around and find out. Sometimes that causes trouble, but on net, expressivity maximization has in fact been the historical story of social scaling, and the source of a great deal of thriving. Because the volume of things that actually get expressed seems to be a function of the expressivity of the system in principle, and the possibilities only become obvious once the system is actually available to fuck around with.

We say more with more expressive technologies. But they have to first exist in embodiments that exceed the needs of known problems. We don’t let the expressivity surplus sit around gathering dust, but we’re also not able to imagine possibilities without the surplus existing first. Creating the surplus is a leap of faith. A different kind of trust — in the ability of humans to figure out good uses for interesting things.

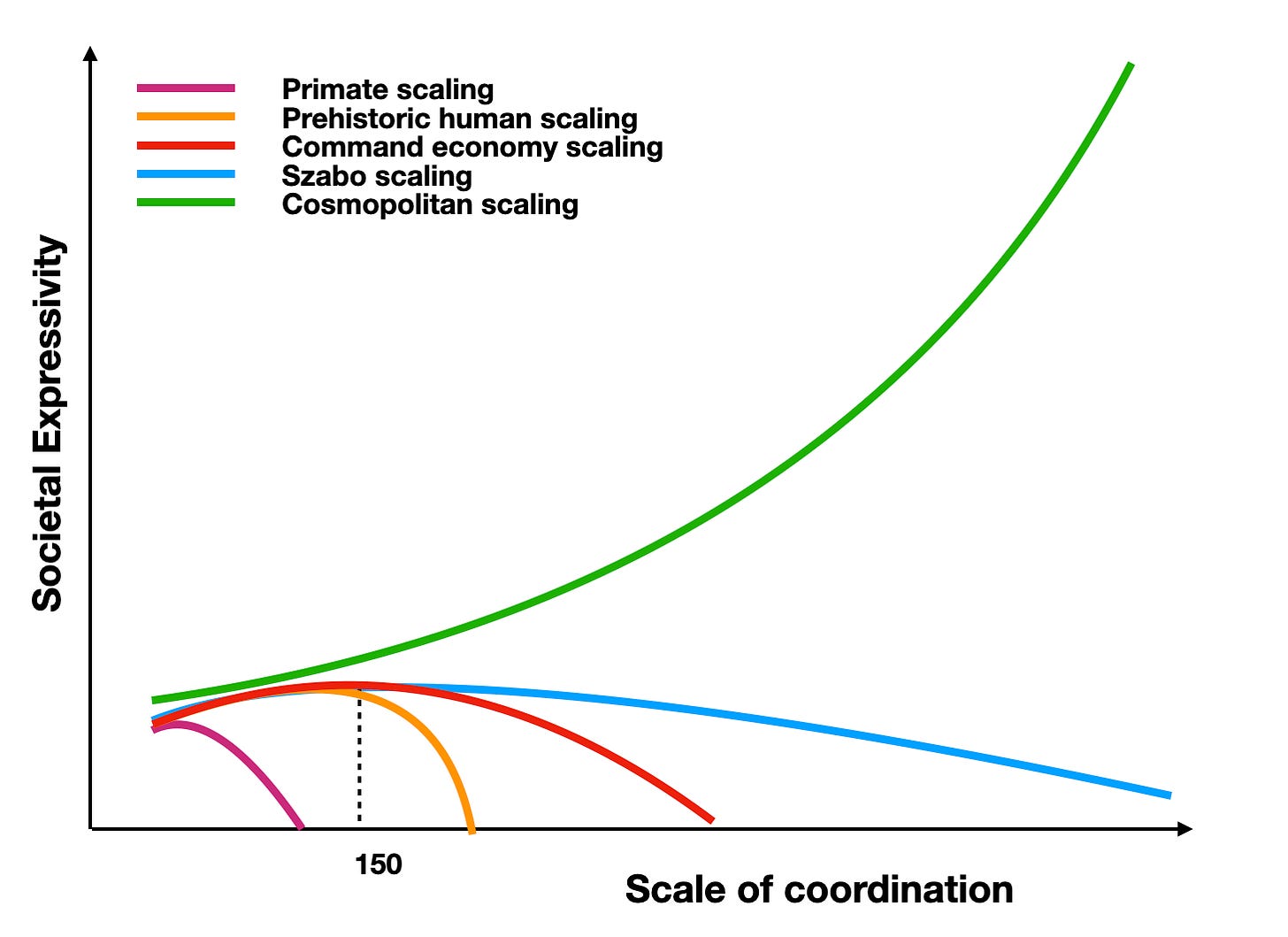

Here’s one way to visualize this historical proposition. It is a speculative graph of the value of scaling architectures in terms of expressivity, versus scale of coordination. Expressivity is roughly the range of things that can be done by applying a scaling architecture (like say command economy, platform economy like AWS, traditional market economy, sumptuary chivalric culture, religious culture, or Korean chaebols) at a particular scale. I’ve illustrated five cases of interest in a speculative, notional way.

Assumptions about how expressivity scales tend to be pessimistic not just because most people default to viewing it through the lens of trust, but also due to more general pessimism about human sociality at larger scales.

Douglas Hofstadter, for example, offered the dismal idea that “apathy at the scale of individuals is insanity at the scale of civilizations,” an epigram that is pessimistic about the quality of collective cognition and care at scale rather than trust, which makes it an epigram that we must skeptically reconsider in light of AI advances and its potential for addressing insanity at scale (so far, we’ve only been clutching pearls about how AI causes insanity in lonely, atomized individuals).

Economics is generally a dismal science, because it allows us to schematize all our pessimism within a single elegant framework. You can express any attitude about the nature of humanity in economics terms, so long as that attitude is a broadly pessimistic and distrusting one. As it says in invisible Masonic ink on US dollar bills after In God we trust, “everybody else pays cash.”

If you want to express optimism about humanity, Szabo scaling is actually as good as it gets in theory. Which is a very depressing state of theorizing. We don’t even have more optimistic theories of social scaling, even though arguably the phenomenology of history justifies it. The history of social scaling is more cheery than our theories of it.

So it’s not surprising that Szabo’s account suggests a rather dismal view of expressivity scaling. His visions of blockchains and their potential only look grand in relation to the very dismal baseline assumptions, and the awfulness of (theorized) architectures in the comparison set, like command economics or Islamic economic philosophy (based on anti-usury commitments). As a result, Szabo scaling is often presented by libertarians as something like the democracy of scaling architectures: The worst one except for all the others.

In the graph of notional scaling curves, broadly libertarian thinkers are very impressed that there is theoretically so much more area under the blue curve (technological humans using trust-minimizing architectures like small sub-Dunbar groups in market-like matrices) than under the red curve (command economy). But I think what I’d call cosmopolitan scaling (the green curve) already delivers better scaling than you’d get if Szabo scaling (blue) were the best we could do. We just haven’t properly theorized how that happens yet.

I’m not an economic historian, but I think the world actually approximated something like Szabo scaling during early modernity, when it was globalizing in a trust-minimizing, ethnocentric/mercantilist mode, without much cultural cosmopolitanism or what Joel Mokyr calls Schumpeterian growth. Arguably, the marginal dividends of cosmopolitanism over that condition, which began to accrue perhaps around the mid 19th century (represented by the area between the blue and green curves), were much higher.

I have made the arguments for this elsewhere (Welcome to the Cosmopolis, Cosmopolis, Metropolis, Nation-State (talk), Towards the Cosmopolitan Supergrid), as have others, like Yuk Hui. I wouldn’t say the theorizing going on is at any sort of satisfactory level, but it’s there, in early forms.

Perhaps you’d sketch the notional graphs differently, but it’s hard for me to seriously entertain the dismal view that everything good in the last few centuries has been the result of libertarian-approved Szabo-scaling mechanisms, and everything else is either some sort of “inefficiency” or cosmetic epiphenomenon.

We’re smarter than that as a species. Even if we don’t know exactly how yet.

Designing Beyond Distrust

I want to reconsider what the phrase social scalability means in more general terms (especially in terms of accommodating AI), but also narrower terms: restricting our attention to human organizational forms. Specifically ones that aren’t based on abstractions like impersonal markets, whose design reflects a trust-minimization overarching design principle.

What is the current state of the art?

Clearly, we are better at coordinating 1000 humans doing simple, non-creative things than 10 humans doing creative things, and we mostly do it by suppressing and constraining the most valuable dimensions of human capability.

One way to react to this (and Szabo essentially does this) is to shrug your shoulders and say “Dunbar’s number.”

Treat it as an inviolable primate-brain constraint to design around, basically. Create scaffoldings out of technological prosthetics to fit our supposedly 150-slot-limited ape social brains. Deploy Great Man types where possible, where they appear, to sustain idiosyncratically higher leverage in the scaffolding.

Libertarians actually prefer this of course. They prefer direct human sociality to remain small-scale, enduring and intimate, leaving social scaling beyond the Dunbar limit to more indirect and impersonal mechanisms ranging from public-key cryptography to markets to voting. Rather paradoxically, as we’ve come to realize in the last decade, they are also actively eager to find end enthrone putative “Great Man” types in unique positions as scalability hacks. Libertarianism in actual practice appears to be a combination of trust-minimization and demigod-construction.

This is not a bad position to take. It’s just… rather conservative? Especially given that the underlying idea of Dunbar’s number appears to be pretty shaky, and its significance overstated? And the even worse shakiness of Great Man theories of history?

Keeping creative human interaction sub-Dunbar, and treating social scaling beyond that as a kind of horizontal “scale out” rather than “scale up” still creates a ton of expressivity headroom for human potential to express itself, with every new technology. To take even a simple example, the Gutenberg Press created an explosion of creative production by means of relatively simple scale-out levers (reproduction and distribution of texts with improving fixity and quality control). Why bother with more?

Well, why leave unused social scalability potential on the table?

I think it’s worth bothering with more because there are qualitatively more interesting dimensions to expressivity. Scale-ups can deliver the kinds of things (moonshots come to mind) that mere scale-outs cannot. Scale-ups add expressivity, while scale-outs typically merely add bandwidth, lower costs, and perhaps increase gross yield from certain valuable statistical phenomena, like the number of outlier geniuses empowered to act.

We can build more kinds of societies than the ones libertarians seem to want — up-to-150-humans units assembled into flat and trust-minimized market-like structures. That’s a tiny fraction of design space. And one based on highly defensive assumptions.

Weakly Positive Trust

To explore the rest of the design space of social scaling futures, we need to work more creatively with weakly positive trust forces.

Just because someone isn’t in my circle of 150 intimates, and just because I wouldn’t give them my passwords and private keys, doesn’t mean they’re socially dead to me, or marks to be game-theoretically outmaneuvered with sketchy market gamesmanship in a Dark Forest milieu. There’s a whole spectrum between full trust and trustless ghosting mediated only by prophylactic market dynamics. The induced design space of weakly positive trust assumptions is not only worth exploring, it contains the most desirable futures for people other than hardcore libertarians.

So how do you do social scaling better with weak trust fields? What if you meet a stranger, and it turns out you both enjoy the same song. Maybe you don’t want to make that person your new best friend and make them part of your social recovery wallet circle. Maybe there’s nobody you can bump from your Dunbar 150 to make room for them. But what can you do together creatively based merely on “likes the same song” as the trust basis? Maybe you can just dance together for one evening, with no need for market mediation? Where does the value of that get accounted for? What sort of socially scaled expressivity does it utilize? Is this sort of thing to be treated as worthless cultural ephemera?

What can you do, in other words, with people whose Dunbar ranks are 151 or higher for you, that trading and markets don’t enable for you? Is the answer really as depressingly limited as “trade with them on markets, or inside transaction-cost optimal organizations, on the assumption they’re out to cheat you”?

Of course not! We already do much better than that!

Coasean economics already points the way to more complex beyond-market coordination. Libertarians often treat even supra-Dunbar Coasean organizations as a sign of distortionary “market inefficiencies” that only exist because transaction costs are too high.

This attitude, I’m convinced, is wrong. Larger-than-Dunbar weak-trust entities exist because we want them to, not because we’re forced to live with them. We like coordinating on scales larger than Dunbar-scale, with mechanisms more expressive than markets and traditional organizations, and with non-minimal trust assumptions. We just haven’t figured out much about how we manage to do so in pre-theoretical ways, and how much more we might be able to, if we properly theorized weakly positive trust regimes.

We’re just really bad at thinking about human behaviors orchestrated at scales above 150 (in a 2014 article I called this the Veil of Scale, in the spirit of the Rawlsian veil of ignorance), so we conservatively choose very limited modes of orchestration at those scales.

But things don’t have to stay that way. The veil of scale can be lifted with technology. And it doesn’t have to be “trust” technology.

Miniaturization and Orchestration

What happens if we try to design for expressivity directly? A good way to explore the question is to evaluate human societal forms in computational terms.

Social scaling for expressivity maximization comprises two practical dimensions, just like compute scaling. Miniaturization and orchestration.

Miniaturization: Shrinking the smallest useful and composable coordination units (vacuum tubes —> ever smaller transistors, now down to a few nanometers). In the case of humans, the “transistor” is the smallest team of humans that can achieve an arbitrary “0 to 1” switch beyond the ability of any single human. Call it a successful collaboration event. Not 0-1 in the heroic Thiel sense, but anything at all. This scale tends to be 2-50 complete humans depending on domain, dedicated 100% to an activity for a period of time. “Startup” is one kind of human transistor. Even “part-time” (or “partial human” in other senses) capability is hard to use effectively.

Orchestration: Scaling at the slowest rate of expressivity loss of that 0-1 switch, with emergent compositional effects being sufficiently faster that the overall scaling is towards accelerating expressivity, as in the green curve in the picture. In the case of computers, that means putting more transistors and capacitors on chips (compute and memory), more chips on boards, more boards in computers, and more computers in datacenters, and using it all at the largest scale you can build software and memory management structures for. In the case of humans, orchestration is organizational operations. Putting workgroups into departments, departments into divisions, divisions into large organizations. And attaching the best possible corporate memory to it all

Aside: I’m emphasizing memory because the scale of the memory architecture you can deploy determines, among other things, how closely you can approximate true “infinite tape” Universal Turing Machines. Memory scalability is likely the most important constraint for all social scaling architectures, including trust-minimizing ones, which is one reason it has emerged as a core research theme for the Summer of Protocols.

A “computer” is a particularly good reference point, since we can ask whether any computer from a tiny Arduino to a global distributed cloud retains Turing completeness in a practically useful way at its maximal scale. What’s the largest number of computers you can orchestrate to solve a non-trivial single distributed computing problem? Right now “train an AI model” is among them (though not the only one — simulating weather or nuclear explosions with supercomputers are problems in roughly the same scale regime).

What are similar orchestration high-water marks for human organizations? Building computer chips, jet engines, and space rockets definitely contend for top spot. Notably, none of these high water marks would likely have been achieved if history had been pure Szabo social scaling. These accomplishments required a good deal of trusting of third parties, betrayals, violence, and bloodshed. And I’m Hobbesian enough in my imagination to hold that the optimal quantities of all those things in society is not zero.

Of course, merely putting enough computers to burn a gigawatt into a data center doesn’t mean you can actually orchestrate a full gigawatt of computing capacity. That merely puts a ceiling on the orchestration potential. I’d guess the upper limit these days is ~100,000 chips (CPUs/GPUs) working on a single problem from within a limited class we know how to wrangle at that scale, with the current state of the art in distributed computing.

With humans, the “miniaturization” side is very primitive. The “startup” is like a vacuum tube or perhaps a single 1950s-era transistor. We don’t even really have ICs (maybe rock music bands of 3-4 musicians that really gel as a tight unit?). As a result, on the orchestration side, fully expressed human creativity (analogous to Turing-complete computing capabilities) basically falls to near zero beyond about 12 people. If computers scaled like this, we would be unable to make reliable circuits with more than a handful of transistors.

Seemingly “big” orgs are really like data centers that might burn a gigawatt at peak utilization, across the aggregate of problems they’re solving at any given time, but don’t actually orchestrate gigawatt-scale problem solving processes. The social scaling going on is much more modest than the height of the compute ceiling suggests. By that analogy, a big Fortune 100 company with 100k employees probably has a maximal creative scale, with say 90% “expressivity loss” of human creativity, (past which point you can’t call it a creativity unit) of about a 100 (ie still sub-Dunbar). Any apparent scaling that happens above that, say a VP running a division of 10,000 people, is put together in mostly sublinear ways limited by the idiosyncratic auteur imagination of 1-2 people designing the org chart. It’s not one creative org of 10k people, but at best 100 black box units of 100 people that are superlinearly creative “inside” but assembled into the 10k unit more like bricks.

The “assembly” level is restricted to relatively simple interactions and interfaces, and relatively uncreative compositional grammars, with only modest (but not zero) emergent creativity. Traditional organizations are architected to maximize manageability rather than expressivity.

Think about that. The most expressive socially scaled entities today are designed around the management bandwidth of the people who can be found to lead them. The most capable of such companies typically turn into idiosyncratic expressions of the management styles of their leaders rather than the collective creativity of all their members. Amazon was once described as being set up like multiple parallel chess games for Jeff Bezos to play. Jensen Huang reportedly does not believe in 1:1 meetings and has 60+ direct reports. While these leaders have proved to have particularly effective styles in comparative terms, it seems weird to assume (for instance) that the most expressive configuration of all the people currently working at Nvidia is the one that happens to fit like a glove around Jensen Huang’s brain.

There’s got to be better ways to miniaturize and orchestrate human coordination.

We’ve barely scratched the surface of social scaling potential of putting humans together. In the computing analogy, we’re at the mainframe era of human social scaling.

AI as Miniaturization

In this view, the big reason for optimism is the emergence of AI. The thing about AI is that it reduces the minimal size of a coordination unit to a pair comprising a partial slice (in both time and function) of a single human and an aggregate snapshot of all of humanity at a given time, delivered through a metered pipeline.

When I chat with ChatGPT, what’s going on is that a fine-grained part of my brain, for example that part that knows stuff about airplanes, is talking to the artificially embodied aggregate of all symbolically expressed human knowledge about airplanes circa August 2025.

How “big” is this entity on the scale of a human brain? It is whatever tokens/second/user capacity OpenAI has allotted your session, depending on what you’re paying, but “competent grad student with weird blindspots” seems to be a good approximation.

So the “transistor” here is perhaps 15 minutes of collaboration where I use perhaps a few hundred training hours worth of my brain’s capabilities. That’s enough to produce (say) a decent essay.

This is an epochal event. Comparable to the invention of the solid-state transistor. Vacuum tubes are fragile and fail easily, like human-human relationships. Human-AI relationships are relatively robust.

Compare this entity with the smallest “transistor” of past eras — a 2-3 person startup team in 2007. An American rural household of 5-8 in 1880. A hundred draughtsmen making engineering drawings on paper in a 1950s firm.

The minimal human-ChatGPT centaur is already tiny by historical standards. And as we get better at unbundling and rebundling ourselves in entanglement with AI, and creating AI itself in less anthropomorphic form factors, the “transistors” of human-machine computation will only get smaller.

And the multi-human scale components will also shrink. Two people with an AI between them will be able to collaborate and coordinate for much lower stakes in the future, with far lower allocation of time and brain cycles together. Chances are, even human relationships might end up being more robust once we introduce AI into relationships (a premise that’s cashed out in somewhat gloomy ways in this short story we just published in Protocolized, but clearly has positive, if less storyworthy potentialities too).

Protocols as Orchestration

While blockchains are a powerful class of protocols, I think Szabo’s view was too narrowly confined to their possibilities due to the fixation on trust minimization. Ironically, the Ethereum world itself showcases some of the most interesting orchestration protocols that owe very little to blockchains, such as managing the entire ecosystem through a mix of purely virtual routine operations and periodic intense collaboration at Ethereum events. This is an orchestration model that relies more on videoconferencing, direct messaging, and software version-control protocols than blockchains.

When you survey the modern technological landscape more broadly, there are vast numbers of modern protocols that deploy humans and technologies in a bewildering array of creative configurations. There is a veritable wilderness of orchestration capabilities out there an orchestration ecology. Yet our theories of organizations and management are weirdly limited to the two antipodes of corporate entities (public, private, or nonprofit) and markets. To the twin media of contracted relationships and tokenized transactions.

The wilderness contains a vast array of poorly theorized forms and collective behaviors — ecosystems, scenes, raiding parties on discords, cozyweb enclaves, DM chats — that rest on “wild” protocols that we are learning to use, but haven’t yet learned to theorize. My theory about the marginal dividends of cosmopolitanism is that it has historically accrued in such pre-theoretical wilderness zones (as we theorize it better, we should be careful not to domesticate these zones in ways that destroy their generativity).

Inject the Moore’s-Law-like miniaturization of coordination capabilities being driven by AI — another ecology with complementary properties, and suddenly vast new design spaces open up in the collision of the two ecologies. Earlier this year, in our distributed AI x protocols workshop in Bangkok, we barely managed to scratch the surface of the potential over the space of a week.

We are only just beginning to understand and work with protocols as media for orchestration, and going beyond the limited orchestral imagination induced by corporate entities and markets (or impoverished and ill-posed topological dichotomies like “hierarchies vs. networks”). Blockchains broke open the conversation by introducing a legible “third way” to orchestrate humans and computers around immutability and time that could not be reduced to either corporate entities or markets. But that was just the beginning.

We are now beginning to see that there are in fact an infinite number of viable orchestration modes, and the more miniaturization by AI progresses, the greater the number of these modes become available for practical design.

We are still at the beginning of the story of non-dismal social scalability, not at the end of it as libertarians seem to imagine. And that’s the cosmopolitan social scaling curve we used to be on for over a century, and I’m interested in getting back on. This time, with AI and protocols serving as accelerants.

Seems implicit in your analysis but friend of a friend also seems likely to add to value above 150. How many friend of friends might there be with levels of Dunbar overlap that are (mostly?) below direct trust levels but add more expressive than just what I might give a stranger? I think a lot. Thanks for this!

Awesome essay! You're in a rich vein here.