Derangements

🟨⬜🟨🟩⬜

The newsletter is back. Paused subscriptions have been unpaused.

A running gag in Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot novels involves the word derangement. Poirot uses it to mean “plans being upset” and his native-English listeners are puzzled because to them it means mental illness in the sense of “Trump Derangement Syndrome.”

For instance, in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, we have this exchange:

“Is there anything else that I can tell you?” inquired Mr Hammond.

“I thank you, no,” said Poirot, rising. “All my excuses for having deranged you.”

“Not at all, not at all”.

“The word derange,” I remarked, when we were outside again, “is applicable to mental disorder only”.

“Ah!” cried Poirot, “never will my English be quite perfect. A curious language. I should then have said disarranged, n’est-ce pas?”

“Disturbed is the word you had in mind”.

“I thank you, my friend. The word exact, you are zealous for it.

And in Dead Man’s Folly, we find this exchange between Poirot and his friend Ariadne Oliver:

“I hope I’m not interrupting you when you’re frightfully busy?”

“No, no, you do not derange me in the least.”

“Good gracious — I’m sure I don’t want to drive you out of your mind. The fact is I need you”

You might think that Poirot’s usage is simply incorrect in English, but it isn’t really. There is a specialized English usage, in combinatorial mathematics, that roughly corresponds to Poirot’s, and sheds light on how he solves mysteries.

What’s more, Poirot’s quasi-mathematical usage and his interlocutors’ folk-psychological usage are in fact related, via a ubiquitous element of the present zeitgeist: vibes.

The connection between the two is hinted at by a famous quote by another famous mystery writer, G. K. Chesterton:

“He may be mad, but there's method in his madness. There nearly always is method in madness. It's what drives men mad, being methodical.”

So let’s talk about method, madness, derangements, derangement syndromes, and vibes.

Derangements in Mathematics

A derangement in the mathematical sense is a permutation of the elements of an ordered set such that no element occurs in its original position. So for example BCA is a derangement of ABC.

We can use the term informally for things being approximately out of place too. So ACB is a partial derangement of ABC.

Poirot’s usage is arguably a loose common-language transposition of this mathematical notion. For example, if I intended to go for a run and then eat lunch, but you show up and suggest lunch right now, I might get lunch earlier with you, and go for a run later (or not at all).

So my plan:

RUN at 11 AM

LUNCH at noon

upon derangement by your inconsiderate behavior, turns into:

LUNCH at 11:30 AM

RUN AT 3 PM (MAYBE)

I suspect Poirot’s repeated idiomatically incorrect usage, despite being frequently corrected, is deliberate. A part of the whole exaggerated foreignness shtick that he uses to disarm adversaries.

But more than that, it also subtly signals his priorities — he approaches murder mysteries as derangement puzzles involving the facts of a case. He tries to exclude irrelevant details, include relevant ones, and then arrange them in the right order so he can see the solution.

Derangement Puzzles

Let’s take a minute to understand derangement puzzles. A basic derangement puzzle is the jumble, where the letters of a word are jumbled up into a full or partial derangement. For example:

LANDIS

This is a full derangement. The solution is ISLAND, and is slightly tricky because the S is silent in the solution, but not in the pronounceable but meaningless derangement. The solution can be hard to see even though it is just two letters moved from the beginning to the end, because you are deaf to the S in ISLAND.

I remember this one particularly, because in college I had a friend who solved it very quickly. He explained that as a kid, before he learned to pronounce it right, he used to pronounce the S, as in IS-LAND!

When it comes to jumbles, spoken English separates LANDIS from ISLAND. You might say the two strings belong in different spoken-English vibe-set: words without and with silent letters. But in the case of my friend, as a non-native speaker, early immunity to the vibes of spoken English actually allowed him to see more clearly.

Wordle (if you don’t know what that is, you’ve been living under a rock, so google it) is a more complex kind of derangement puzzle. You could call it a derangement++ type puzzle, where you have inclusion/exclusion steps in addition to rearrangement steps.

The goal is to guess the 5-letter word of the day using at most 6 guesses, to generate colorful little non-spoilery solution patches that you can share and brag about on Twitter. Dozens of variants of the basic puzzle have appeared.

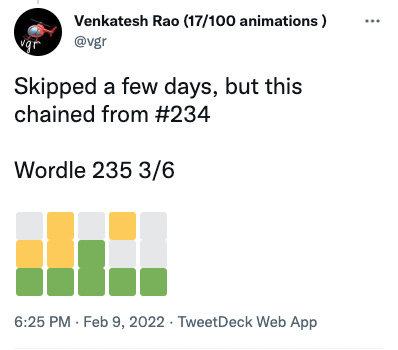

Here’s my 3-step non-spoiler solution to today’s puzzle. 😎

If you haven’t seen these before, a gray is a wrong letter, a yellow is a right letter in the wrong place, and a green is a right letter in the right place. I’ve never hit a perfect derangement while solving a puzzle, but if you did, it might look something like this:

A strip of yellow would indicate you’ve hit a special anagram of the solution where you have all the right letters and none of the wrong ones, but no letter is in the right place. It’s a pattern I’m waiting to hit: the perfect derangement. Aiming for interesting wrongness is one way to play.

These colorful little checkerboards have been instrumental in making Wordle a part of the whole January-2022 vibe. As my buddy Drew Austin remarked, it’s not as satisfying as the sea shanty vibe we were enjoying this time last year, but as I will argue, it is a better fit for 2022, and a sign of genuine progress from “sugar and tea and rum” vibes.

In Wordle, the implied set is the entire alphabet, with repetitions allowed. You have to iteratively work to exclude the letters that don’t belong, include the ones that do (possibly multiple times), and arrange them in the right order.

Every arrangement you try must be a real word. Here for example, is my 4-step solution to yesterday’s Wordle (rather appropriate, given our murder theme). FRAME is the right answer, but BRAVE, EARTH, and AEGIS are also real words, just the wrong ones.

But they do reveal things about the right word — if you pay attention to the colors rather than the meaning of the wrong word.

They also reveal — and this is a crucial point — something about my mood while solving the puzzle. What was I vibing with while solving my Wordle?

So you can’t have nonsense strings as attempts.

This is a significant detail for our broader meditation on derangements.

Allowing nonsense strings would at once make the puzzle easier and more boring, and perhaps even anxiety provoking. You could try letters in strict order of frequency, especially frequency at particular positions (Y for instance, is more common at the end of a word than at the beginning). A computer might brute-force an efficient shortest path via the most information-rich nonsense strings and not care, but it wouldn’t be fun for humans.

It would perhaps even be very stressful to witness. I’m told human Rubik’s cube solvers and Go players are really stressed out by the Eldritch horror solution paths found by AIs.

One common way people try to work with this requirement that each guess be a real word is to begin with strategically chosen words that happen to include the most common letters. AEGIS, SOARE, and AROSE are popular because they include the most common vowels and common consonants.

As you’ve probably noticed, many Wordle players have nerded-out over the perfect information-theoretic approach, to try to “win” with the fewest tries, by identifying the best start words, and letter substitutions to target.

Not me. I’m a vibe-player. Wordle is my daily horoscope.

I treat the game as a divination tool rather than a game of prowess. I recently tweeted my divination key for interpreting my daily Wordle score:

6 tries: you’re going to hell

5 tries: purgatory

4 tries: shot at heaven, keep trying

3 tries: Heaven unless you mess up

2 tries: Heaven guarantee

1 try: gods making you mad with power to destroy you

While I’ve gotten my share of 3s and even a 2, I don’t seriously try to minimize my score. Why mess with the message the gods are trying to send you?

What’s more, I usually play by Wordlechain rules. Rather than trying to use the “best” start word, in Wordlechain you use the solution to the previous day’s puzzle as the start word for today’s puzzle. For example, in the first example I shared, which I solved today, I used yesterday’s solution, FRAME, as the start word. I also enjoy thinking about the astrological significance of the words themselves, under the aegis of a brave Earth.

Astrology is very vibey.

With wordlechain you’re constructing an unbroken chain of legal words, with a solid green word every few rows. That’s your unique, personal wordlechain. It encodes the cosmic destiny the gods have written for you. A whole personal cosmic vibe constructed out of a daily puzzle. The story of your life told through little divination vibe patches.

Wordlechain is an infinite-game version of Wordle. The goal is not to win, but to continue the game. It’s a way of playing that vibes great with the blockchainy world.

James Carse would have approved.

So now that we know what derangements in math are, and how they relate to particular kinds of puzzles, and the various aesthetic sensibilities you might bring to playing them, let’s get back to murder mysteries.

Mysteries as Derangements

Poirot didn’t play Wordle, but he did like “order and method,” and was in fact famous for the extremely orderliness of his daily life.

While solving a case, he would often build card castles to help him concentrate. The task of precisely arranging cards to make a pyramid helped him unconsciously bring order to the deranged facts of the case.

Order-and-method behaviors are a source of both characterization and humor in the Poirot novels. Poirot is constantly rearranging or straightening out elements of his physical environments to his taste, and is visibly upset by unnecessary disorder he cannot control. But it is mostly an aesthetic sensibility for him. It’s not that he cannot tolerate disorder but that he has an unusually strong preference for order.

Where Poirot is merely quirky, detective Adrian Monk (a character obvious inspired by Poirot), of the eponymous show Monk, is severely traumatized by environmental derangements. He is frequently frozen into inaction or driven to psychosis by too much chaos.

Adrian Monk has severe, debilitating, clinical OCD. Not only is he naturally predisposed to it, but a weird upbringing has turned it extreme. And the traumatizing loss of his wife Trudy to a car-bombing has made it nearly as extreme as that of his brother Ambrose Monk (who is a pathologically OCD version of Mycroft Holmes).

Keep that relationship between trauma and quirky vs. debilitating levels of desire for orderliness in mind. It’s at the heart of the method-madness link.

In the Poirot tradition of “cozy” mystery solving, murder mysteries are derangement puzzles, and the solution process is roughly analogous to the rational solution process for puzzles like Wordle: you try to exclude irrelevant details, include relevant ones, and then arrange them in the right order so you can see the solution.

The subgenre name cozy is revealing — there is a whole Wordle/crossword-puzzle solving vibe to both the stories themselves (body in a locked library in a mansion with a fixed number of suspects) and the aspirational ideal experience of reading them (curled up on a couch with a warm blanket and hot chocolate on a cold night).

If you’re Poirot, you try to start with the best start word and race to the solution in the fewest attempts. There is of course a good reason for speed, and for trying to minimize the number of false hypotheses tried along the way to the solution. The murderer might get away or kill again if Poirot is not quick enough to the 🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩 .

One of Poirot’s “start words” is that the most likely suspect in a murder is the spouse, the E of murder mysteries. That’s like the SOARE hypothesis in a murder mystery. Poirot, like efficient Wordle solvers, is not just a rationalist, but a proper Bayesian.

Usually, but not always, Poirot’s approach also leads to the simplest, most elegant solution, even though human crimes don’t necessarily conform to the Occam’s razor principle. Both Poirot and Monk have dealt with their share of cases where the simplest answer was not the right answer.

The murderer of course, usually tries to do the exact opposite thing: Arrange the facts in the most misleading way possible, to throw detectives off the trail. For Poirot and the murderer, the facts of a case are a dynamic adversarial puzzle.

Amusingly enough, there’s an adversarial version of Wordle called Absurdle, where the computer tries to dynamically thwart your solution attempts.

Both these patterns of exclusions/inclusions/arrangements of facts are rational. The detective attempts to reveal the the truth and see justice served, the murderer attempts to obscure the truth and escape.

But it is not these rational solutions that make murder mysteries interesting, it’s all the non-rational (but as we will see, not irrational) solutions that litter the story, thanks to the sense-making strivings of characters who are neither the detective, nor the murderer.

Solutions that plausibly hang together at first glance, and temporarily satisfy those who offer them, but don’t actually work. Solutions that are generally distracting annoyances, which Poirot has to clear away so he can see the real solution. Solutions that present as narratives, but upon inspection do not cohere well enough to function as narratives.

Solutions that are not quite random jumbles, and not quite coherent narratives, let alone ones that work and point to the truth of what actually happened.

Solutions that are not explanations but vibes.

We need a little explainer on vibes here, before we can get back to mysteries.

Explanations versus Vibes

Vibes are popular right now, and have supplanted memes as the currency of internet culture.

I’ve decided I hate them the way Poirot hates silly theories of a murder, and for much the same reasons.

Kyle Chayka wrote a great feature about them last year. Here’s a good bit:

In the social-media era, though, “vibe” has come to mean something more like a moment of audiovisual eloquence, a “sympathetic resonance” between a person and her environment, as Robin James, a professor of philosophy at U.N.C. Charlotte wrote in a recent newsletter. What a haiku is to language, a vibe is to sensory perception: a concise assemblage of image, sound, and movement. (#Aesthetic is sometimes used to mark vibes, but that term is predominantly visual.) A vibe can be positive, negative, beautiful, ugly, or just unique. It can even become a quality in itself: if something is vibey, it gives off an intense vibe or is particularly amenable to vibes.

On social media, a vibe is most commonly shared in the form of a mood board image of an assortment of items. Much of the work in communicating the vibe is done by what you choose to include or exclude, and the arrangement doesn’t really matter much. There is no “right answer” to the question of how to convey a vibe. There are only aesthetically superior and inferior choices.

For example, a set of objects — say a hoodie, a gaming laptop, heavy boots, a case of Red Bull, and a stack of Japanese comic books — labeled “type of guy.” That’s a mood board conveying a gamer vibe. Type of guy is in fact a popular genre of vibes.

I have my own definition of a vibe in the context of derangement puzzles ranging from Wordle to murder mysteries to the Great Weirding.

A vibe is the feel of the least unsatisfying wrong resolution of a mystery

Or if you prefer pithy, vibe-y, aphoristic definitions, a vibe is an emotion pretending to be an explanation.

It is no accident that a vibe collection is similar to the collection of clues you might be presented with early in a stylized murder mystery (the game pieces and cards of the popular board game Clue are pure cozy vibe). The difference is, you use them to feel good about the state of the mystery rather than to solve it.

A vibe is not like a random jumbled-up string of letters. It is like a guess in Wordle that is a real word, but not the right word, and has enough green and yellow in it to serve up a pleasing dopamine hit.

A vibe that works does so in a specific way: It demystifies a mystifying situation long enough that your anxiety at things not making sense subsides, and you can stop paying investigative attention to it.

But as I once wrote, a decade ago, in ancient pre-Weirding times, demystification is not the same thing as understanding. Satisfying curiosity, or alleviating anxiety, are both easier tasks than uncovering the truth. Replacing an undesirable emotion with a desirable one is easy. Getting at truths is hard.

How long does it take for a vibe that works to work? Not very long at all. We’re talking seconds, not minutes or hours. Emotions work fast. That’s why the creation and curation of vibes on TikTok and elsewhere is an impressionistic art form. Things don’t have to have the logic and coherence of a story. They don’t have to satisfy your intelligence for 2 hours like a movie does. They only have to satisfy your emotions for 5 seconds.

A vibe that works as a vibe, however, is unlikely to work as an explanation. It might contain clues to an actual solution, but unless you’re motivated by the truth rather than by the replacement of unpleasant emotions with pleasant ones, they won’t lead you to the solution.

Imagine you’re playing Wordle, but neither trying to win efficiently, nor in an aesthetically pleasing and inefficient, but still correct way like my Wordlechain approach.

Instead, you just try to create an interesting pattern of green, yellow, and gray, indifferent to whether or not you ever hit a row of solid green, a “right answer.” A beautiful evolving tapestry of wrongness.

This is the puzzle-solving equivalent of bullshit — you’re indifferent to the truth or falsity of a solution. You only care about the vibe induced by the pattern of colors.

A couple of greens, a couple of yellows, and a grey, arranged in a pleasantly symmetric way, might be good enough. You don’t have to get to all greens. The four yellows and a green of AROSE might be vibey enough for you, “green enough,” even though it doesn’t mean the same thing as SOARE (a young hawk).

Note that the wrongness of a vibe is not the same thing as the rgouh egeds of a mreely imricpsee or iancuctrae aswenr. It is generally an actually wrong answer. One that is not even in the neighborhood of the right one, despite containing several of its elements.

Because a vibe is meant to soothe, not explain.

So vibes that work do not explain things, and are not expected to; they merely aestheticize them in an emotionally satisfying way that drains motivation to seek actual solutions.

What about a vibe that does not work even as a vibe? We’ll get to that. But let’s return to Poirot and murder mysteries once again.

Vibes and Mysteries

The great pleasure of a well-crafted murder mystery is that you get to see a precise and accurate explanation dissipating the FUD of a dozen vibey non-explanations clouding your perception of events.

In the context of murder mysteries, a vibey non-solution is an arrangement of facts to evoke a type of (murderer) guy, or absent a suitable murderer guy, a type of explanation that is temporarily emotionally satisfying without actually being correct.

In a Poirot mystery, the air is ripe with vibey non-solutions pointing to types of guys or types of explanations without actually nailing a guy or an explanation. Mood boards of clues selected and arranged to evoke the feel of a preferred kind of story.

They envelop the mystery like a cloud of farts. And Poirot holds his nose and tries to clear them away.

Some common ones you’ll find in Poirot novels (and most cozy mysteries):

The “respectability vibe” solution: A character tries to arrange the facts in the most comforting way possible, while also hiding or drawing attention away from facts that are personally embarrassing or threatening to them, even if they have nothing to do with the case.

The “prejudice vibe” solution: Morally compromised participants have already decided who is good and who is evil (often a predictable outgroup, like servants, foreigners, or gipsies), and try to arrange the facts in a way that leads to the evil being guilty and the good being innocent.

The “conviction-friendly vibe” solution: The overworked police try to arrange the facts in a way that makes for the most convenient and low-effort closing of the case. While they don’t actively want to let the murderer escape or convict an innocent person, they hope that the easy and obvious solution turns out to be the correct one.

The “sensationalist vibe” solution: A character with a weakness for drama will often offer solutions involving intrigue, spies, romantic figures, secret societies, and so on. Poirot’s companion Captain Hastings often went for these solutions, as such companions often do.

The “tropey vibe” solution: Murders are a self-referential genre, and characters in them seem to only read the worst sort of pulp tier. So they offer up tropey “butler did it” type solutions.

What is common to all these approaches to accounting for the facts is that they don’t aim to definitively establish what actually happened. Instead, they aim to alleviate sense-making anxiety, and make the person offering the solution feel comforted and unthreatened. They aim to generate the right vibe from the disturbing (and deranged) circumstances.

Poirot of course, listens to these explanations, usually without contradicting them, looking for the patches of green and yellow in the stories he’s told by other characters, seeking to collect and arrange them into a solid green solution.

But sometimes none of these kinds of satisfying vibey solutions can be constructed, in which case the characters typically offer up the most interesting kind of non-rational solution of all: it must have been a passing madman.

It is of course never a passing madman. It is always a principal character, and they always have a sane motive.

Derangement Syndromes

The appeal (to the characters in the story) of the “passing madman” solution is that it lets you off the hook entirely.

You don’t have to explain anything because the arrangement of facts doesn’t have to make sense. You don’t have to act against any of the principals in the story because the culprit is not just mad, but an unknown stranger in whom the principal characters have no stake at all.

The problem with the “passing madman” solution though, is that if that’s the “least unsatisfying wrong resolution” to the mystery you can conjure up, not only is it not going to work as an explanation, it is not even going to work as a vibe.

A “passing madman” is a very unsatisfying “type of guy.”

“Events don’t need to make sense” is a very unsatisfying “type of explanation.”

So unsatisfying in fact, that if you’re the sensitive type, like Adrian Monk, it might even drive you into a frenzy of looking for better solutions.

Which brings us to the connection between (mathematical) derangement puzzles, madness, and derangement syndromes.

Trump Derangement Syndrome is one of several derangement syndromes that have gone endemic through the Great Weirding. In fact, you could argue that the Great Weirding is a collection of derangement syndromes. Another good name for it would be the Great Derangement.

I tweeted this inventory, but there are many more.

So what’s a derangement syndrome? Here’s a definition:

A derangement syndrome is a failed vibe

In other words, it does not even work as a vibe, let alone as an explanation. It does not replace a disturbing emotion with a comforting one. It does not alleviate anxiety for long enough for you to look away. It does not demystify the mystery enough for you to lose obsessive interest in resolving it.

The characteristic symptom of a derangement syndrome is that emotional responses to it are not stable. You go from manic exhilaration at temporarily “owning” an adversary to utter despair at a turn for the worse.

And between those two extremes, you engage in frenzied bursts of effort to try and actually figure things out. That’s how you get things like that early exhibition of Trump Derangement Syndrome, the infamous “time for some game theory thread” by a Democrat strategist.

That’s the method in the madness — and madness that arises from being methodical. Frenzied psychotic reasoning that makes you crazier and crazier.

Being methodical doesn’t work while you’re in the grips of a derangement syndrome. Every arrangement of elements you try to make sense of things fails. The gods are against you. It’s day after day of 6-try or failed Wordles. You’re drowning in vibes that don’t work, losing your grip on reality — and on your ability to actually solve puzzles.

Fictional detectives are not immune to derangement syndromes. They are in fact more sensitive to them. It’s just that they’re also better at reasoning their way out of them.

But not always.

In an episode of Monk, the mystery has caused a garbage collection strike and garbage is piling up in San Francisco (the show is set in an ancient time when this wasn’t actual policy).

Adrian Monk has a psychotic break.

He goes into a manic frenzy, spinning crazy theories while trying to single-handedly clean up the garbage, until his cop buddy Captain Stottlemeyer takes him to an electronics clean room.

There, he finally calms down enough to get over his Garbage Derangement Syndrome and solve the mystery.

And reason — and garbage collection — return to San Francisco.

Yes, that’s fiction, but there’s hope in the tale there.

The Return of Reason

The ubiquity of derangement syndromes is good news — it is a good thing when vibes don’t work.

It means you are forced to work for the return of reason (but not a retvrn to reason — that’s a whole other toxic vibe). Mere aesthetics will no longer do.

If you settle for the least unsatisfying wrong resolution to a mystery because you are too emotionally drained to seek the right resolution, that is not a good thing.

Those suffering from derangement syndromes, unlike those lost in soothing vibes that work, are motivated to move on from suffering derangement to actually solving mysteries. When vibes fail you, you have to seek actual explanations. You have to do the work.

This perhaps, more than anything else, is why the vibe of early 2022 is the Wordle vibe, where the vibe of early 2021 was the sea shanty vibe. Then, we were hurting so badly, even the nonsense words (what’s a Wellerman? What does it mean for the “tonguing to be done”) that produced good sugar-and-tea-and-rum vibes were preferable to trying to “solve” the pandemic and invasions of Congress by QAnon shamans.

Now, a year later, in a small way, we are beginning to tentatively prepare the ground for the return of reason, by gravitating towards a vibe that might help us exit this era of seeking solace and refuge in vibes.

In a small, safe, cozy way, Wordle gives us a means to experience once again the pleasures of accurate and precise reasoning in pursuit of truths, and look past mere vibes that feel good to worlds that make sense.

But learning to trust “order and method,” and like Hercule Poirot, gently setting aside the comforting and vibey non-solutions after extracting whatever clues they offer, is hard.

Patiently collecting the right pieces, dropping the wrong pieces, and carefully arranging them so that you can step back and say, that’s the way the world actually is, is hard.

Resisting the temptations of vibes and mood boards is hard.

Getting through the manic-depressive addictive pleasures of derangement syndromes is hard.

But with Wordle, we’ve made a small start in a safe place. A start that suggests that we are no longer satisfied with vibing our way through life, as we have been for half a decade now. That we are ready to begin thinking again.

And then maybe the master vibe that is the Great Weirding will begin to retreat, and the Great Derangement will start to yield to order and method, one yellow or green square at a time.

Very well crafted piece, Venkat! Very satisfying ;)

As I read through your breakdown of the concept of a vibe, interestingly, the one example that kept popping up in my head was Michael winning the China debate with Oscar. He marauds home purely fueled by vibe, but not a shred of reason.

He only soothes the audience's anxiety and worries about China becoming #1 and "merely aestheticizes them in an emotionally satisfying way that drains motivation to seek actual solutions."

Excellent!

A very optimistic take on Wordle. I like it! Now I fear for what happens to Wordle when the NYT, vibe monetizers, decide to change things up..