Is it okay to sit out the culture war? The question nags like a guilty conscience. We live in an age where silence is read as cowardice and every hesitation is counted against you in the ledger of loyalty. To step aside, to resist joining battle in the name of values, feels like a moral failure. Yet here, in the tension between action and restraint, the meaning of courage begins to fray. What is courage, if it can be summoned equally by the soldier in a just cause and the zealot in a senseless one?

Sloptraptions is an AI-assisted opt-in section of the Contraptions Newsletter. Recipe at end. If you only want my hand-crafted writing, you can unsubscribe from this section.

We’re reading Montaigne’s essays this month in the Contraptions book club.

The ancients were never of one mind. Aristotle placed courage on the battlefield, a mean between cowardice and recklessness. To die bravely was the highest proof of manhood, though the Stoics later reminded us that enduring illness or facing death with calm equanimity was no less courageous. Aquinas, with a Christian inflection, called this fortitude: not only meeting enemies in combat but bearing long suffering, illness, and martyrdom. In Confucian thought, courage (yǒng) was inseparable from righteousness (yì); bravery without justice was folly. Buddhism held up abhaya, fearlessness rooted not in fury but in compassion and detachment from self. Hindu texts offered both Arjuna, reluctant on the battlefield and exhorted to take up arms for dharma, and the ascetic saint, enduring hunger and time itself with unyielding calm. The samurai made courage (yūki) the fearless acceptance of death, shaped by loyalty and honor. Across these traditions runs a thread: courage is not only the clash of steel but the endurance of suffering and mortality, not only the willingness to act but the strength to restrain.

Montaigne, writing in a later century, sharpened the point. In On Cruelty he warns that “those natures that are sanguinary toward beasts discover a natural proneness to cruelty,” and that cruelty often “arises from a cowardice that flatters itself with the guise of force.” Cruelty, he insists, is fear disguised as valor. To torment another creature is to manufacture counterfeit courage, to mask hesitation with domination. The hesitant are told their fear will be forgiven if only they prove themselves by silencing an opponent—aggression recast as bravery when it is nothing more than noise hiding dread.

Leaders have long known how to turn this trick. It is how Europe marched into the trenches in 1914, where honor rhetoric transformed caution into cowardice. It is how America invaded Iraq in 2003, told that decisive action was bravery and prudence timidity. It is how Mussolini persuaded Italians that war itself was the proof of manhood. To sit out, to resist, to question—each was branded weakness. In such moments populations are gaslit into mistaking cruelty for courage.

Yet not all wars are of this kind. There are times when cruelty must be confronted head-on, when restraint would mean complicity. When the Nazis advanced, when slavery split the United States, when empires refused to loosen their grip, there was no peaceable path. Here courage had to be martial, had to be public, had to risk life. The difficulty lies in knowing which kind of moment one inhabits: the avoidable folly or the unavoidable reckoning.

Between these poles courage is constantly distorted. Antisocial personalities thrive in the confusion: the psychopath whose lack of fear masquerades as bravery, the sadist who endures discomfort to inflict pain, the manipulative leader who brands hesitation cowardice and aggression valor. What was once a virtue becomes a trap. Populations are goaded into battles they might otherwise avoid, urged to hide their fear behind cruelty rather than admit it and endure it.

Commerce has its own theater of courage, though it is rarely honored with the language of epics. Merchants are expected to be prudent, to preserve capital, to bend with power, and if they survive they are praised as shrewd rather than brave. Yet history shows that business too can be tested in the same crucible as soldiers and martyrs. Sometimes the trial is whether to align with authority for profit, sometimes whether to risk ruin for principle. The cowardly response is common: German firms that supplied the Nazi regime with chemicals and armaments, American companies that profited quietly from apartheid South Africa, countless trading houses that grew fat on slavery while calling themselves respectable. These are not merely cases of greed; they are also forms of cowardice—fear of losing position, of standing apart, of being ruined. Montaigne would have recognized them as cruelty wearing the mask of valor.

There are other stories, quieter, where courage lay in restraint. The Quaker merchants of England and Pennsylvania, for instance, who refused to invest in the slave trade when it was the richest vein of commerce. They chose the slower, harder path of transparent dealing, and in time their reputation for honesty became a form of capital that outlasted empires. In Japan, the shinise—old family firms still operating after centuries—endured famines, wars, and regime changes by holding fast to practices rather than chasing every political wind. Their courage was patience: surviving hard times without moral collapse or reckless gambles. In South Africa, a handful of companies resisted the full logic of apartheid, refusing to enforce certain hiring codes despite pressure. They did not always proclaim it loudly, but they endured, and when the system fell their reputations allowed them to rebuild in good conscience.

The absence of this kind of courage is conspicuous in our own time. In the United States, in the thick of the culture war, corporations have mostly chosen the coward’s path. They puff themselves up with slogans of virtue when it is safe, retreat the moment they face pressure, and flatter themselves that prudence is courage. In truth it is complicity. Worse still, some have gone beyond silence, actively and enthusiastically rallying behind illegitimate abuses of power in the name of corporatized nationalism—trading integrity for favor, mistaking obsequiousness for strength. To refuse both reckless posturing and craven surrender, to endure lean years without selling out principle—this would be commercial courage. Yet in the current landscape, it is vanishingly rare.

This inheritance is ours. The culture wars of the past decade are not wars of survival or liberation but wars of performance. They grow from real grievances—inequality, migration, failing institutions—but blossom into spectacle: militias training in the woods, lone actors with rifles, mobs storming capitols, digital swarms conducting harassment campaigns. These are cultivations of cruelty, stoked by figures who know how to sell aggression as courage. Influencers and politicians deploy the same trick as past demagogues: hesitation is weakness, refusal betrayal, restraint timidity.

If cruelty is cowardice in disguise, then much of what passes for courage in today’s culture wars is cowardice writ large. The online warrior, the street brawler, the partisan agitator—each appears fearless, but their bravado often conceals a deeper fear: fear of irrelevance, of change, of mortality, of loneliness. Their violence is not strength but an attempt to mask fragility.

So the opening question returns: Is it okay to sit out the culture war? To sit out as apathy is one thing; to sit out as resistance is another. It may be the highest form of courage available to us now. To refuse the summons to cruelty, to endure being called weak, to resist being manipulated into battles staged for someone else’s gain—this is courage of a quieter, sterner kind. It is the courage of the patient enduring treatment, of the dissenter who refuses the mob, of the merchant who endures hardship without surrendering to corruption, of the one who faces mortality without disguise.

Courage does not always raise a sword; often it lies more in restraint than in action, in lowering the hand clenched for battle rather than striking with it. To sit out the culture war in this sense is not cowardice but clarity, a clarity braver than any banner waved in anger.

Recipe

Summarize the writing protocol in brief

Here’s a brief summary of the writing protocol we just followed:

Provocation First — Open with a sharp, questioning provocation that frames the essay (Montaignean mode: start from lived doubt, not thesis).

Meditative Flow — Write in continuous prose, no hard sections, but with implicit breakpoints where topics shift.

Layer Traditions — Begin with a survey of courage across antiquity (Western + Asian), then carry forward through Christian, civic, medical, and modern psychology.

Montaigne Anchor — Weave in Montaigne’s essay on cruelty with direct quotation, using it as a moral hinge: cruelty = cowardice disguised.

Historical Dialectic — Present thesis/antithesis through historical cases (avoidable vs. unavoidable conflicts), using narrative illustration instead of bullet points.

Modern Application — Apply to the culture wars, treating them as performative, manipulated conflicts closer to WWI/Iraq than WWII.

Commerce as Test — Add a meditation on commercial courage, with positive and negative historical exemplars, sparing theory references (MacIntyre, Knight).

Return to Question — Circle back to the provocation: sitting out as cowardice or courage. Resolve by reframing restraint as a higher form of courage.

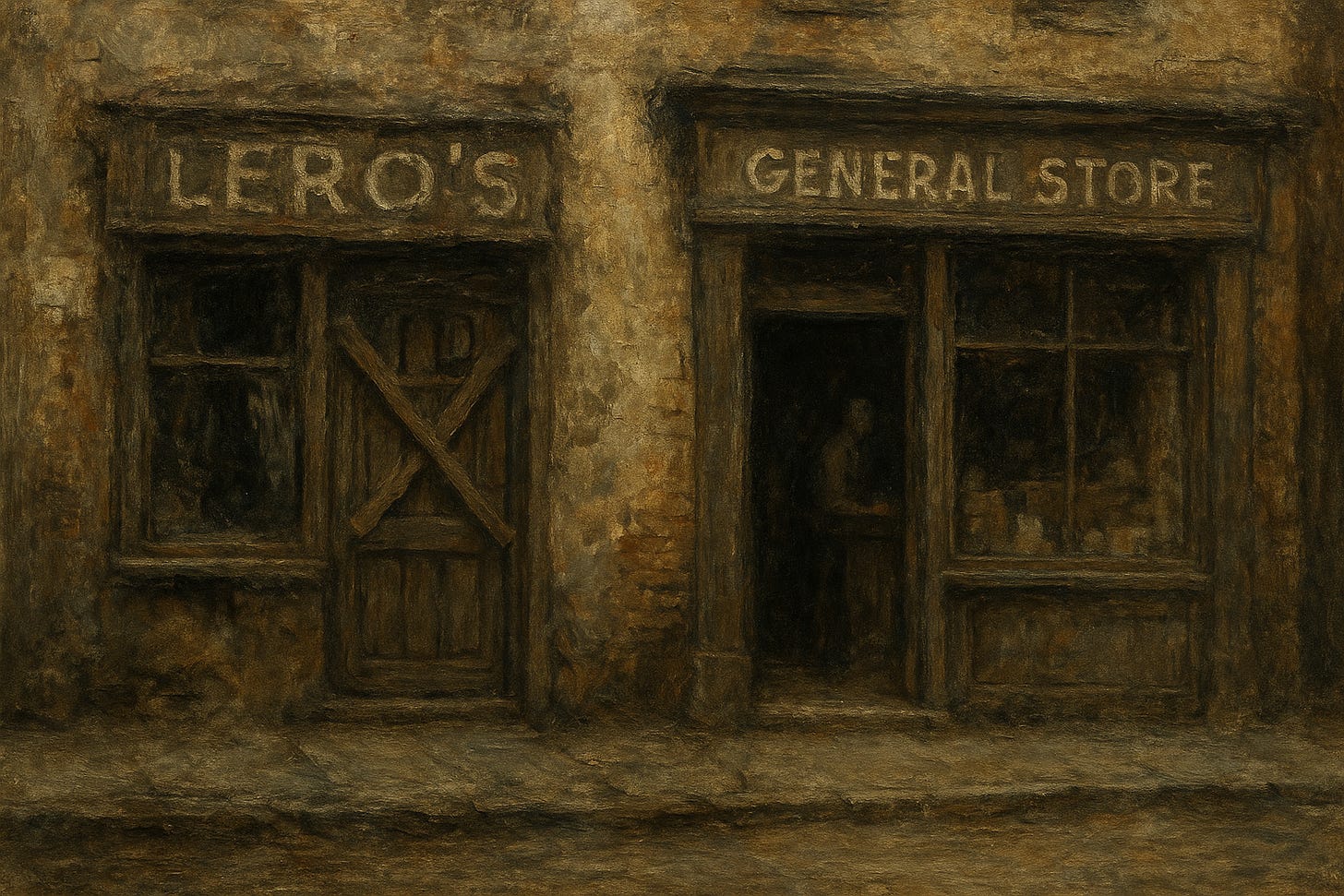

Images as Meditative Pauses — Use painterly, grainy images (battlefield, hospital corridor, storefronts) as visual echoes of thematic pivots.

there's also a "pace-layering" frame -- there's simply much more to be done for the maintenance and growth of culture than participating in the loudest, fastest, most conflict-rich layer of activity. just because there's a war going on doesn't mean teachers, cooks, gardeners, mothers, librarians should leave their posts. if we collectively lose sight of that then we're well-&-truly f'ed

The second half of this was really good.