GUTS: The Grand Unified Theory of Striving (or Slacking )

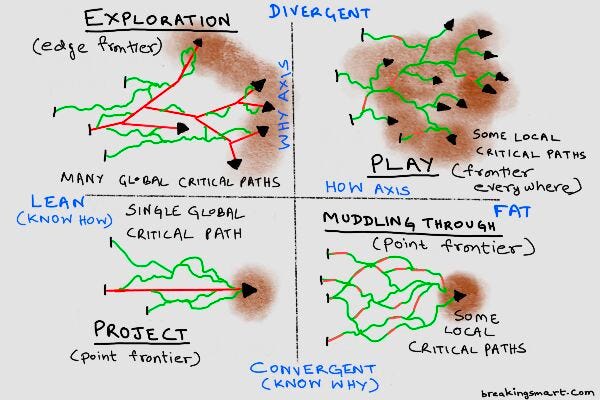

It's always a good day when two good dichotomies collide to create a great new 2x2. This week, two of my favorite dichotomies relating to work, lean vs. fat and divergent vs. convergent came together to produce a most excellent 2x2 I call the How and Why 2x2. Ambitious name, huh? There is a LOT packed into this diagram, and it compactly consolidates a lot of my thinking over the past couple of years, so take a moment to contemplate it and reverentially admire its sheer grandeur before reading on. I like this enough that I might make a larger pretty poster version. I call the associated theory the Grand Unified Theory of Striving (or Slacking), or GUTS. Whether the S stands for striving or slacking depends on which side you're looking at the picture from. If it's striving, it is guts as in guts-and-glory. Maximal, optimal, effort. If it's slacking, it is guts as in sensing subtle things in your guts -- while in relaxed play mode.

The key to this 2x2 is the interplay of critical paths (the straight red bits) and non-critical paths (the wiggly green bits). This interplay creates effort that is both meaningful (you have a good answer to why you're doing something) and efficient (you know how to do it well) under conditions of ambiguity and uncertainty. That's what I call flourishing, or eudaimonia. Takes GUTS.

The How and Why 2x2

1/ You probably think of critical paths as a subset of actions in a plan that determines the overall timeline. This is the view taught in operations research textbooks and lean/agile training.

2/ Delays on the critical path delay the project, speed-ups of the critical path speed up the project. In other words, things you care about depend on how you do critical things.

3/ Generalizing, the critical path is a zone where there exists a sensitive dependence of ends on means. Critical paths capture sensitivity of effort optimality to disturbances.

4/ Activities not on the critical path have slack: some variables, such as start times, or processing rates, are underdetermined. We are formally indifferent to the values they take.

5/ This understanding of critical paths isn't wrong per se, but it is incomplete and unilluminating. Why do critical paths exist at all? Why is there only one? Are we really indifferent to slack on non-critical paths?

6/ Critical paths exist where two conditions hold: you're optimizing a system for a single goal, and have a global model of how to achieve it, ie an overall plan.

7/ In other words, you're in a convergent and lean operating context. The dreaded bottom-left doghouse in the 2x2. You know why you're acting, and you know how to act. This is a project.

8/ Knowing why gives you one half of the information you need to optimize things: the objective function, such as time to market or delivery.

9/ This isn't always time by the way, though that's the one operations research textbooks discuss the most. It can be any global variable or single combination of variables.

10/ If you were optimizing for cost in shipping for instance, the critical path for fuel cost might go through the ocean-shipping leg, and you might practice slow steaming, ie the critical path is about giving up time for money.

11/ The key here is that you have a single answer to why, even though it might result in a very complex formula describing what is to be optimized.

12/ A shipping company aiming to maximize profits from its fleet might optimize a giant, hairy function of time, fuel costs, depreciation, turnaround, and demurrage.

13/ There can be even be uncertainty bands around all of them. Fuel costs can be volatile. The customer may be willing to forgive some delays.

14/ Zooming out, a new backhaul load may be found changing the economics of the round-trip voyage. A new refurbishment process may alter the depreciation curve on the ship.

14/ But it's still a single answer to why. Whether you're maximizing expected profit or a certain profit, the answer to why is still "make money."

15/ What happens when you don't know why you're acting? This is another way of saying you're not sure what is of value in the activity, and what is meaningful to you.

16/ Some people (and companies) react to not knowing why with frozen inaction. They can't act at all unless they know with certainty why they're acting.

18/ Other people (and companies) react with frenzied, overwrought "ROI engineering" turning everything into some sort of portfolio optimization theory.

19/ But the smart response to not knowing the answer to why is to simply pursue many, divergent goals that test different motivations. And this pursuit can be efficient even if its ends are unclear.

20/ You might drill many exploratory oil wells, try many musical instruments on for size, sample many subjects before choosing a major.

21/ You don't even need an abstract goal like "find the most productive oil well" or "find the instrument I'd like to learn to play." Such false clarity can even backfire.

22/ Through exploration, you expose your thinking to novelty, so you might discover entirely unexpected answers to "why" in your peripheral vision.

23/ Like "actually I'm in oil drilling because I like geology and building great drilling equipment" or "I'm really learning a musical instrument to connect with other music lovers."

24/ But as long as the application of the means can be optimized, you don't actually need clarity on the ends. This is pretty much the definition of professionalism.

25/ In the famous fable of the 3 stonecutters (Drucker version), the second stonecutter doesn't care that the goal is building a cathedral.

26/ He is happy being good at stonecutting, and is going to optimize stonecutting whether or not it's on the critical path towards the particular goal.

27/ This can be bad in mission-centric situations, but can actually be a good thing in exploratory contexts.

28/ Neil Armstrong reputedly had ice water in his veins. He was picked because he was a highly skilled test pilot, not because he had a romantic fixation on the moon.

29/ The craziest part of the Apollo 11 lunar landing is the story of how Armstrong handled an unexpected challenge of landing the Eagle.

30/ With fuel low, hovering over an alien world with 1/6 earth gravity, in a weird kind of flying contraption, he had to improvise a landing when the planned one didn't work.

31/ His first words "one small step..." may have been underwhelming as a poetic answer to why, but he was there for the how. The ultimate 2nd stonecutter in an undefined cathedral.

32/ As the picture in the top-left quadrant shows, the result of optimizing around how without knowing (or knowing but not caring) why is a connected, branching web of critical paths, all exploring a frontier edge rather than a single critical path marching to a point.

33/ This is why you can "train" for unprecedented and unknown adventures. You don't always have to know why to get the how right.

34/ This is the reason you have the cliche of selling pickaxes to miners. You can optimally exploit known answers to how without caring about why.

35/ Whether you're pursuing gold, or fool's gold (pyrite) you still need a pickaxe, and those can be efficiently supplied, as can passage on a steamship to the frontier.

36/ Together, the left half quadrants are the lean half of the picture. So long as you know how in some global sense, you can operate lean whether or not you know why you're doing what you're doing.

37/ It's a different story on the right half. Not knowing how kills the possibility of global critical paths. This is running fat. I've written before about fat thinking.

38/ You run fat when you don't know why you're expending effort, or how to expend it efficiently, or both.

39/ When you know why, but the how is too complex (example, "Get to the moon") you can only optimize bits of the system at a time (like "lunar module pilot selection and training"), so you can only have short stretches of locally critical paths.

40/ As the 2 pictures on the right show, tightening the red bits doesn't improve overall system optimality because they're interconnected by wiggly green bits.

41/ Green, remember, is non-critical paths, paths with slack. In fat regimes, the slack exists because you don't know what to optimize for, not because there's a tighter parallel activity.

42/ The picture on the lower right is muddling through (the phrase is from a famous 1959 paper I found via the book Obliquity, ht Taylor Pearson for that reco).

43/ When goals are big and complex, but still defined enough that they can serve as a singular focus, you muddle through, iteratively refining means and ends as you figure it out.

44/ Global critical paths exist when you can optimize all the way through to the end goal. You muddle through when the end goal is too complex.

45/ Think of it as problems that do have a global utility function, but it is some sort of unknowable god utility function that you can only see one clause at a time.

46/ You can at best know it imperfectly and in bits and pieces, so you can only act on that knowledge imperfectly and in bits and pieces.

47/ Finally, we have the top right quadrant, which is always the best quadrant in quadrantology. Here you have no good answers to either why or how.

48/ The result is play. Divergent, fat behavior. You can still have little critical paths, but they're largely aesthetic in significance. They say nothing about efficiency or worth.

49/ There are several different useful ways of reading this 2x2. Let me walk you through 4 such views: a values view, a criticality view, a context view, and a learning view.

49/ The values view of the 2x2 is that the four quadrants represent different distributions of speculative value (as in, "stuff that is worthwhile and meaningful to pursue")

50/ When you know why, value is concentrated at a point, where explicit goals and utility functions may be definable. We usually call this focus. You can define what you care about.

51/ When you know how, but not why, value is spread out over a frontier enveloping the reachable "fringe" of the exploration tree. You can get there efficiently, but not realize the value efficiently.

52/ When you don't know how or why, the value zone is spread out all over. Being too efficient along the way can be counterproductive: your critical path might zoom through the most valuable zone.

53/ The convergent versus divergent distinction (the y/why axis) can be understood in terms of the value zone smearing out from a point to a band or area.

54/ Now for the criticality view. The lean versus fat distinction (x/how axis) is about whether the "lean tree" (the subset of the entire plan that is critical paths) is connected or disconnected.

55/ If you delete all the green bits, the two pictures on the left will still have a connected red path or tree. But the two on the right will become fragmented into a bunch of red bits.

56/ The third way of thinking of this is context: the top right is the biggest kind of big picture, the most zoomed-out, with maximal context. The other three are various sorts of zoom-ins.

57/ This is why projects have to be "carved out" of bigger, messier pictures. There are two dimensions to "carving out" a project. Restricting context in terms of ends, and restricting it in terms of means. Why and how restrictions.

58/ Focus is why-context restriction: zoom in to find a zone of concentrated value (little brown patch) that's not too smeared out, so you can converge on it with some clarity. This draws missionary types like flies to honey.

59/ Criticality is how-context restriction: zoom in enough so that there's a connected single critical path spanning the whole picture, this admits a notion of global efficiency and creates jobs for mercenary lean-six-sigma stonecutter types.

60/ The bottom left is maximally zoomed in: you've restricted both why and how so much that you've got yourself a project. If you hate this state you become an artsy precious-snowflake consultant like me.

61/ Your anxiety tolerance determines how far you go towards this state. This has two elements, ambiguity tolerance and uncertainty tolerance.

62/ Low ambiguity tolerance will drive you towards focus (divergence to convergence) via why-context restriction. You don't mind improvising, but you want to be sure you're getting somewhere meaningful, like Mars.

62/ Low uncertainty tolerance will drive you towards global criticality (fat to lean) via how-context restriction. You don't care where you go, but you want to get there efficiently, and professionally, and possibly win "best stonecutter" along the way.

63/ The top left and bottom right are medium-zoom projects. The activity is either too exploratory, or too complex, to be a clean-edged, carved-out "project."

64/ You need trial and error either on the why (exploration, top left) or on the how (muddling through, bottom right) to realize any sort of value.

65/ And of course, in the top right, you need trial and error on both why and how, and value could be anywhere, and you have to let go anxieties and play. Which brings us to learning.

66/ The fourth view is the learning view. Slack (green bits) represent untapped how-learning potential, forks in the critical path represent why-learning potential.

67/ Critical path bits are places where you're actively learning, and close to exhausting the learning potential. Green is green because you currently don't care to learn, not because there's no learning to be done.

68/ A system is at a local how-optimum if there's no further tweaks possible on the critical paths, and no way to move the criticality to the green parts.

69/ Under such conditions, you usually need a change in the why to create more how-learning potential. This is disruption, and hard to do internally because the how-optimized system has a lot of inertia.

70/ Conversely, if you are unable to reshape ambiguity in why (the brown zone spread) further, you may need a breakthrough in how to change the why equilibrium.

71/ Finally, we can make a distinction between closed and open learning. Normal how and why learning will not shift a problem across the quadrant boundaries.

72/ Normal learnings -- refining the why to lower ambiguity, or refining the how to lower uncertainty -- will typically still keep you in the same quadrant.

73/ In other words, you can't lean the complexity out of a fundamentally fat problem like say "getting to Mars" or "tackling climate change".

74/ Nor can you focus the ambiguity out of a fundamentally divergent problem like "grow the economy" or "discover new science wonders."

75/ Under normal circumstances, the only way to move quadrants is to rein in ambition. Make the problem smaller rather than your striving more powerful. Shrink how/why context boundaries.

76/ But there is one exception. When "breakthroughs" or "revolutions" happen, a problem can jump quadrants without narrowing either why or how context.

77/ When a powerful new means becomes available, like computing, a "muddle through" problem might acquire a global critical path. You might suddenly be able to optimize end-to-end.

78/ More subtly, when a powerful new paradigm becomes available, you may suddenly collapse a lot of why-ambiguity without narrowing the focus of an ambitious exploration.

79/ Shifting to "assume the speed of light is a constant for all observers" suddenly lowered the ambiguity of a lot of seemingly separate problems in physics.

80/ For these kinds of breakthroughs, you need a different kind of learning. The kind that comes from open-ended attentiveness rather than means or ends-focused attention.

81/ This is why play is the top-right quadrant, the One Quadrant that rules them all. It simply pays attention to context without being attached to either means or ends. It simply does without asking why or how too urgently.

82/ Paradigm shifts in perspective might create connections between the local learning contexts of two competing goals: "Hey let's sell pickaxes, then we'll make money no matter where the gold is!"

83/ Breakthroughs in means might create connections between two disconnected segments of local critical path "hey, let's use a computer to optimize time AND fuel costs at the same time!"

84/ To put it all together: before you ask why you're doing what you're doing, or how to do it well, ask yourself where you are. Convergent or divergent? Lean or fat?

85/ If you can answer those two questions, the rest will fall into place.

Feel free to forward this newsletter on email and share it via the social media buttons below. You can check out the archives here. First-timers can subscribe to the newsletter here. More about me at venkateshrao.com

Check out the 20 Breaking Smart Season 1 essays for the deeper context behind this newsletter. You can follow me on Twitter @vgr

Copyright © 2018 Ribbonfarm Consulting, LLC, All rights reserved.

As an approximation, I think it might be fair to say the top-right quadrant is „Fox-land“ (finding direction) whereas the bottom-left is „Hedgehog-land“ (developing momentum)?! And top-left and bottom-right are transition-states where more and more Hedgehogness competes with the Foxyness of play.