Software development exhibits a deep asymmetry in time. There is almost always a lower bound on how long it takes to implement an idea: a duration set by its legible complexity—the visible work of design, coding, integration, and testing that competent practitioners can anticipate. But there is no corresponding upper bound. The same idea may ship in days, or consume months, or fail to converge at all. This asymmetry is not an accident of poor planning or individual error. It arises because implementation unfolds within a distinct region of possibility where uncertainty compounds, feedback degrades, and effort no longer maps cleanly to progress.

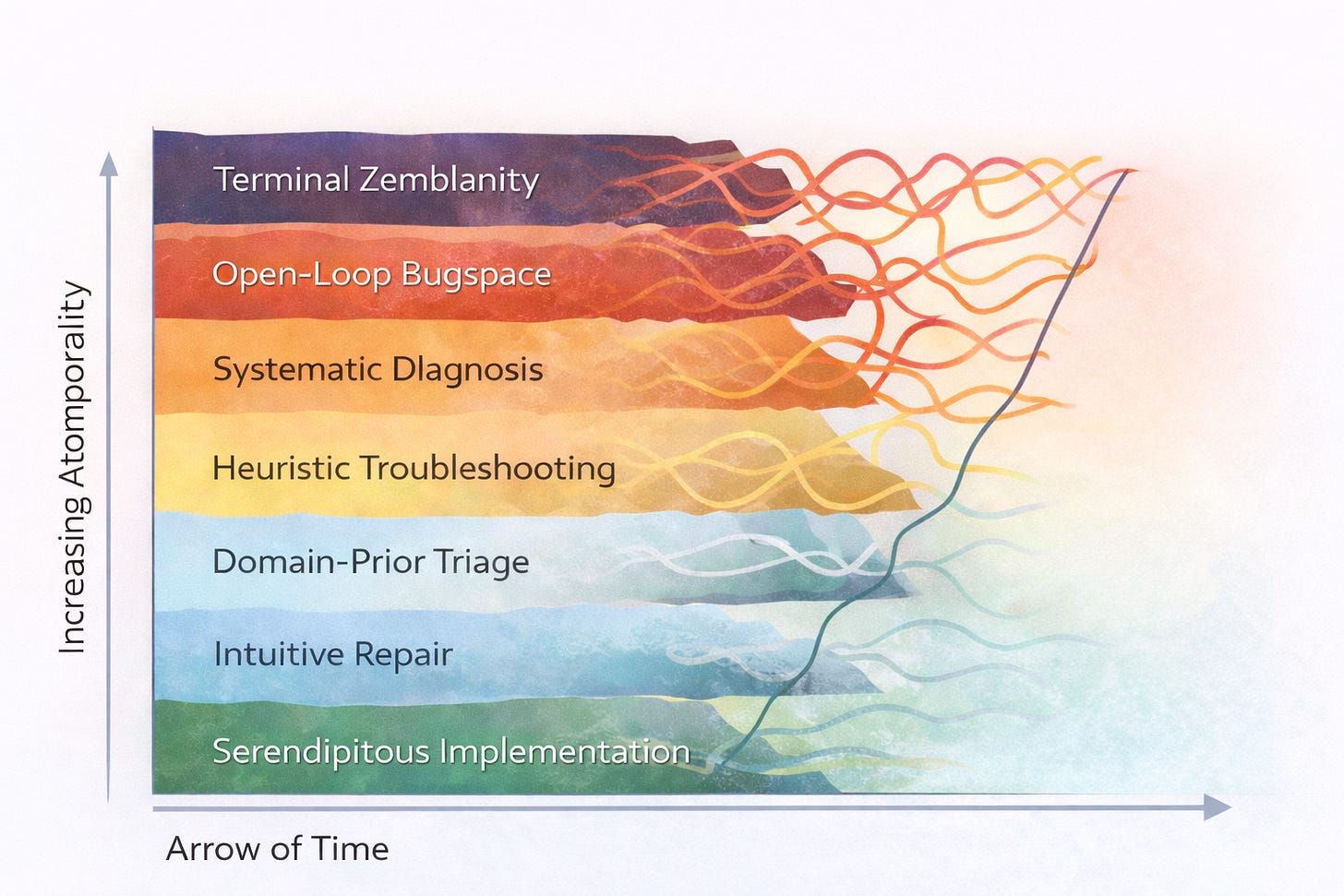

At the bottom of this region lies the Serendipitous Implementation layer: the surprisingly lucky case where code works more or less as intended on the first pass. This regime is real, if rare, and forms the psychological baseline against which all other experiences are judged. Above it lie increasingly unlucky regimes of zemblanity: the unsurprising, grinding bad luck of things going wrong in predictable but hard-to-escape ways. As projects derail from serendipity into zemblanity, they enter what we can call bugspace: a layered landscape in which time flows differently, sometimes stretching, sometimes looping, and in the worst cases failing to progress measurably towards completion at all.

We refer to the temporality of bugspace as a dilated temporality, in both an objective sense (the project end-date stretches in potentially unbounded ways) and a subjective sense (the experience of time distorts, as the correlation between effort and progress weakens, causing immersive derealization in bugspace). The former is the primary sense of the term in what follows; the latter is a frequent consequence that creates the sense of being lost.

Bugspace is stratified a stratified space. Intuitive local fixes give way to probabilistic triage, then to systematic troubleshooting, and finally to open-loop states where neither effort nor ingenuity reliably reduces uncertainty. What drives project drift up these layers is not any single problem, but the accumulating activation of independent but non-exclusive dimensions of uncertainty. Each additional activated dimension stretches time, weakens feedback, erodes the expectation of convergence, and amplifies the sense of being lost in bugspace.

Sloptraptions is an AI-assisted opt-in section of the Contraptions Newsletter. If you only want my hand-crafted writing, you can unsubscribe from this section.

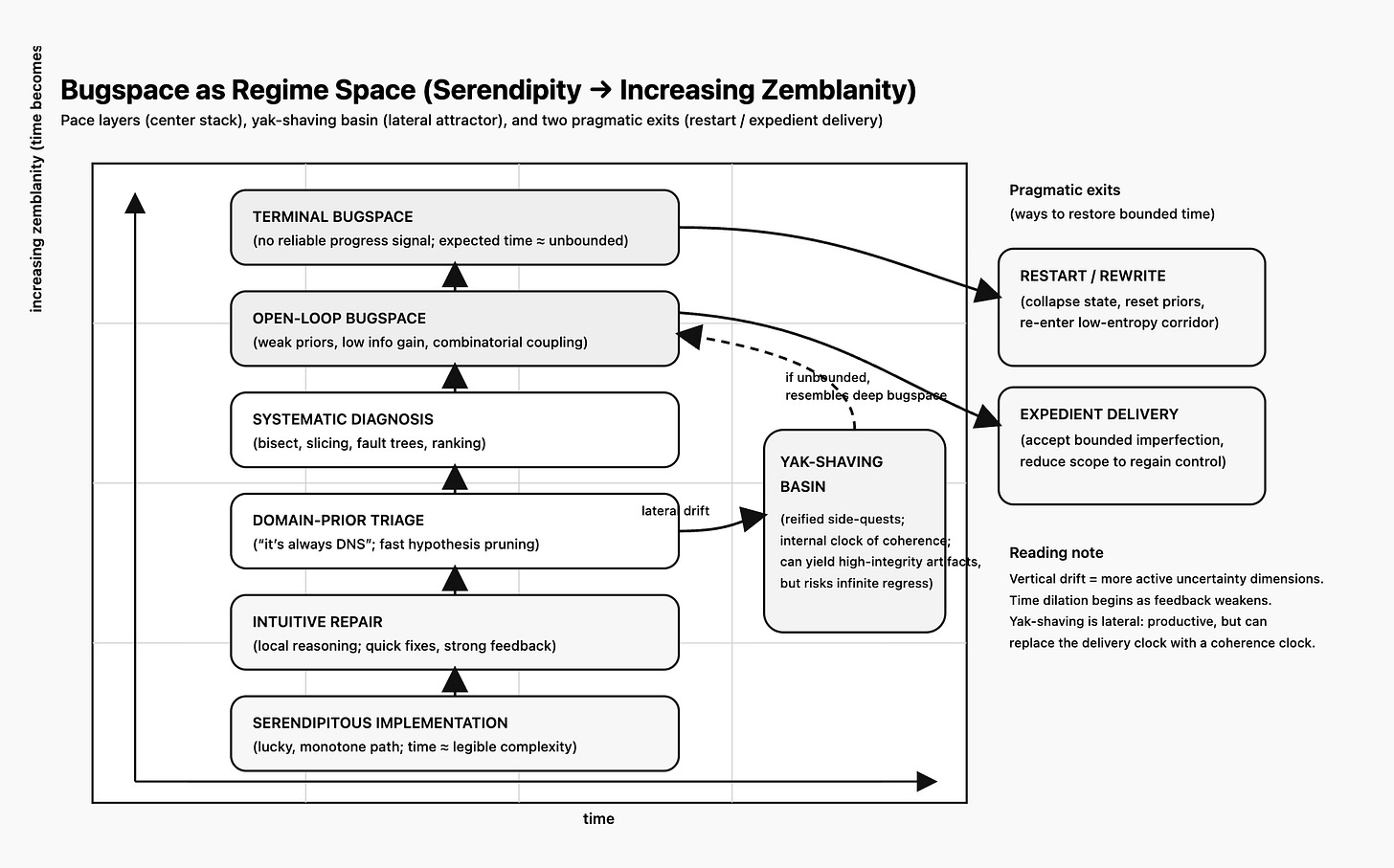

Before examining those dimensions, it is useful to name the strata explicitly, and adopt a loose pace-layered mental model of bugspace. At the bottom is Serendipitous Implementation, where progress is monotone and time is well-behaved. Above it lies Intuitive Repair, where small bugs are resolved by local reasoning. Next comes Domain-Prior Triage, where experience-driven heuristics dominate. Higher still are Heuristic Troubleshooting and Systematic Diagnosis, where divide-and-conquer, slicing, and fault trees are required. At the top lie Open-Loop Bugspace and finally Terminal Zemblanity, where progress becomes indistinguishable from random walk and abandonment or rewrite becomes rational.

As we go up the stack, the number of activated dimensions of uncertainty increases. The flow of the project implementation changes from smooth and steady laminar flow near the bottom, to viscous and tangled high-vorticity non-Newtonian flows near the top. The experienced temporality changes from banal and chronological to surreal and atemporal.

Dimensions of Implementation Uncertainty

1. Statistical Structure of Bugs

Software defects are not uniformly distributed. Empirical studies consistently show heavy-tailed behavior: a small fraction of modules account for a large fraction of defects, and a small fraction of bugs consume a disproportionate share of debugging effort. This skew persists across languages, domains, and decades.

The implication is that average-case reasoning is misleading. Most fixes are cheap; a few are catastrophically expensive. Bugspace is defined by these tail events. When a project encounters one, time dilates abruptly—not because effort decreases, but because variance of rewards explodes.

2. Estimation Failure and Fat Tails

The folklore of software estimation—Hofstadter’s Law, the ninety–ninety rule, and Brooks’ Law—encodes a real statistical phenomenon rather than mere pessimism. Empirical syntheses show that while median overruns may be moderate, variance is extreme and tail risk dominates outcomes.

Software is not unique in underestimation, but it is distinctive in how defect-driven rework interacts with evolving requirements and partial observability. Time estimates fail because they assume bounded variance. Bugspace violates that assumption.

3. Graph Structure of Implementation Space

Implementation can be modeled as navigation through a graph of partial artifacts, where nodes represent program states and edges represent edits or decisions. For many problems, there exists a narrow corridor of low-cost paths from idea to working system.

Derailing from serendipity means leaving this corridor. At that point, the task ceases to be navigation and becomes diagnosis. The topology changes from directed motion toward a goal to search over explanations for inconsistency, and the time dynamics change with it.

4. Computational Hardness of Debugging

Formal models make this shift precise. In model-based diagnosis, debugging reduces to identifying a minimal set of faulty components that explains observed failures—a minimal hitting-set problem, which is NP-hard in general. Related formulations using minimal unsatisfiable subsets and minimal correction subsets exhibit the same hardness.

The significance is experiential rather than theoretical. Bug-free implementation feels easy because it stays in a tractable region. Debugging in deep zemblanity feels qualitatively different because it is qualitatively different.

5. Troubleshooting Techniques as Complexity Containment

Developers respond to this hardness by imposing structure. Binary search over history, delta debugging, program slicing, and spectrum-based fault localization all attempt to restore tractability by exploiting constraints.

Each technique works by temporarily reducing dimensionality. Each fails when its assumptions break. This explains why debugging progress often comes in bursts followed by long stalls.

6. Bayesian Priors and Domain Lore

Much practical debugging relies on sharply peaked Bayesian priors. In distributed systems, “it’s always DNS” persists because DNS failures explain many symptoms with high probability. Similar priors exist for time bugs, cache invalidation, and off-by-one errors.

These priors are rational responses to skewed distributions. When evidence aligns, triage is fast. When it does not, zemblanity deepens.

7. Human Cognitive Limits

Debugging is a cognitive task. Developers must generate, maintain, and revise hypotheses under uncertainty. Success correlates strongly with forming a correct hypothesis early.

As you venture deeper into bugspace, hypothesis space grows faster than human working memory can manage. Time stretches not only because the problem is hard, but because the solver is human.

8. Information Bottlenecks and Observability

Debugging is an information-gathering process under noise. Failures are indirect, delayed, and context-dependent. Logs may be missing; tests may be flaky; instrumentation may perturb behavior.

As information gain per experiment shrinks, time dilates. Observability tooling collapses bugspace by increasing signal; opacity amplifies zemblanity.

9. Socio-Technical Amplification

Bugs live in organizations, not just codebases. Ownership boundaries, communication delays, and incentive misalignments lengthen diagnostic loops.

Adding people to a late project increases not only communication overhead but diagnostic fragmentation. Bugspace expands to fill organizational cracks.

10. Epistemic Drift and Moving Targets

Many bugs are not violations of a fixed specification but artifacts of evolving or inconsistent expectations. Debugging becomes negotiation. Fixing one interpretation breaks another.

Time becomes unbounded because the target itself is unstable.

Yak-Shaving

There is a distinctive response to bugspace that is neither abandonment nor expedient compromise: yak-shaving. Yak-shaving is the deliberate decision to treat a local defect, awkward dependency, or janky subsystem as a first-class problem, worthy of its own standards of correctness and time horizon.

Yak-shaving is the reifying of bugspace into an unbounded set of side-quests.

Yak-shaving preserves local integrity by expanding scope. It is attractive to high-integrity developers because it aligns with professional identity. Unlike restarting, it retains accumulated constraints. Unlike expedient repair, it refuses bounded imperfection.

Its danger is infinite regress. Each improvement justifies the next. Time ceases to be measured against delivery and is indexed instead to internal coherence. Yak-shaving occupies a stable basin between productive debugging and terminal zemblanity: capable of producing high-quality artifacts, yet indistinguishable from failure if allowed to become unbounded.

The Topology of Bugspace

The ten dimensions are independent but not mutually exclusive. Each debugging episode occupies a point in a high-dimensional regime space. In principle this yields a combinatorial explosion of regimes each with its own temporality and dilation character; in practice they collapse into a small number of bands of distinct temporalities.

Here is a more practical diagram/map of the pace-layer mental model described earlier, with the yak-shaving basin and typical exit pathways illustrated.

Low-dimensional regions correspond to serendipity or mild zemblanity, where time is bounded. Mid-dimensional regions produce fragile, punctuated progress. High-dimensional regions are open-loop, where time ceases to be meaningfully bounded.

From deep bugspace, there are three exits. Restarting collapses dimensionality by discarding history. Expedient delivery regains control by accepting imperfection. Yak-shaving inhabits bugspace by redefining the clock in solipsistic ways. Each exit resets time differently.

Bugspace is therefore not merely where projects slow down. It is where the governing clock changes.

The Codebase Remembers

Software systems remember how they were made. Decisions taken under uncertainty, stress, or open-loop time leave lasting structural imprints. Codebases carry something like trauma: not necessarily damage, but memory.

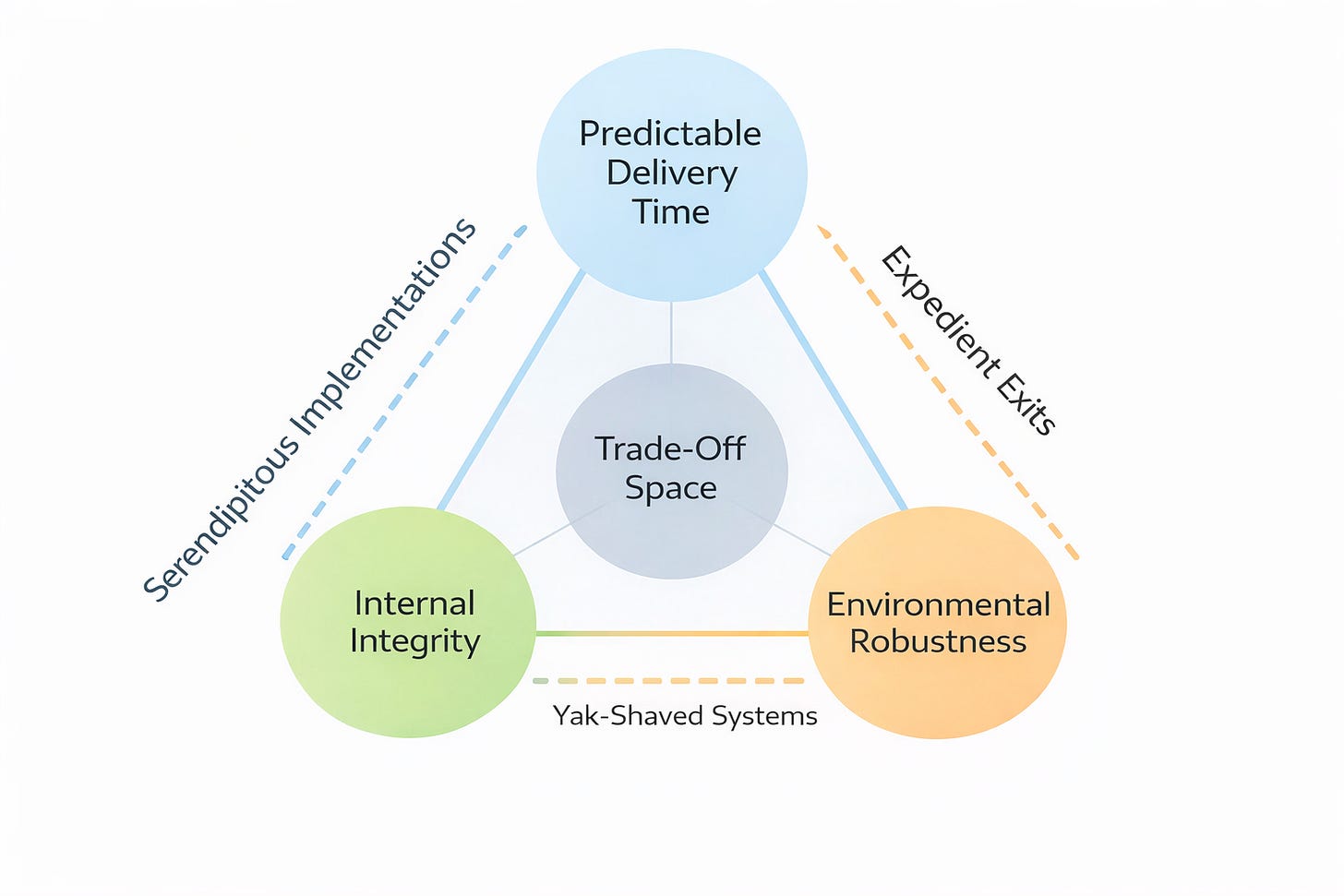

Serendipitous implementations tend to embody strong, coherent worldviews—elegant but brittle outside their assumed context. Systems that pass partway through bugspace often become tougher, if less pure. Bugspace acts as a selective environment.

Longevity offers a unifying metric. By longevity we mean the time a system remains useful, adaptable, and non-fragile under change without heroic maintenance. By this measure, some exposure to bugspace can be beneficial, acting like annealing in materials science: relieving internal stresses, redistributing flaws, and increasing toughness.

Too much exposure, however, overworks the material. Complexity accumulates without corresponding strength. Systems become exhausted rather than robust.

A practical rule-of-thumb resembles a familiar triangle. At most two of the following can be strongly optimized: predictable delivery time, internal integrity, and environmental robustness. Serendipitous implementations favor delivery and integrity. Expedient exits favor delivery and partial robustness. Yak-shaved systems favor integrity and robustness while abandoning delivery guarantees.

There is no universally correct choice. The mistake is choosing implicitly. Software development mastery consists not in avoiding bugspace, but in recognizing which temporal regime one inhabits, which exit one is taking, and what kind of artifact one is willing to leave behind.

Bibliography

Statistical Structure of Bugs and Debugging Effort

Ostrand, Weyuker, Bell (2005). “Predicting the Location and Number of Faults in Large Software Systems.”

A canonical empirical study showing that defects are heavily skewed toward a small fraction of modules. Supports the claim that bug-fixing time is dominated by tail events rather than averages.

Zeller, Hildebrandt (2002). “Simplifying and Isolating Failure-Inducing Input.”

Introduces delta debugging and demonstrates experimentally that some failures require exponentially many steps to isolate without structural constraints, reinforcing the “time dilation” aspect of bugspace.

Chilimbi et al. (2009). “Holmes: Effective Statistical Debugging via Efficient Path Profiling.”

Shows that statistical fault localization can dramatically reduce debugging effort when assumptions hold, but degrades sharply otherwise—an empirical illustration of regime shifts.

Estimation Failure, Time Overruns, and Software Lore

Moløkken-Østvold, Jørgensen (2003). “A Review of Software Surveys on Software Effort Estimation.”

A meta-analysis showing systematic underestimation and high variance in software schedules. Supports the claim that software estimation fails structurally, not incidentally.

Flyvbjerg, Budzier (2011). “Why Your IT Project May Be Riskier Than You Think.”

Introduces the idea of “fat-tailed” project risk in IT, aligning closely with the essay’s lower-bound / unbounded-upper-bound framing.

Fred Brooks (1975). The Mythical Man-Month.

Source of Brooks’ Law and foundational lore about non-linear time behavior in software projects; still relevant because the underlying dynamics have not changed.

Formal Models of Debugging and Computational Hardness

Reiter (1987). “A Theory of Diagnosis from First Principles.”

Formalizes diagnosis as a minimal hitting-set problem, establishing NP-hardness. This is the strongest formal support for the claim that deep bugspace is computationally hard.

Marques-Silva et al. (2013). “Minimal Unsatisfiable Subsets: Theory and Practice.”

Shows that isolating minimal causes of inconsistency in logical systems is intractable in general, directly analogous to debugging inconsistent program states.

Zeller (2009). Why Programs Fail.

A practitioner-facing synthesis that connects formal diagnosis theory with real debugging practice. Useful bridge between theory and lived experience.

Troubleshooting Techniques and Their Limits

Ball, Eick (1996). “Software Visualization in the Large.”

Early evidence that visualization can compress debugging time by improving observability—but only up to a point.

Agrawal et al. (1993). “Debugging with Dynamic Slicing and Backtracking.”

Classic paper on program slicing as a complexity-reduction technique, reinforcing the idea that debugging tools work by temporarily collapsing dimensionality.

Bayesian Priors, Debugging Lore, and Heuristics

Murphy-Hill et al. (2015). “How We Refactor, and How We Know It.”

Shows how expert developers rely heavily on pattern recognition and prior expectations when diagnosing code problems.

“It’s Always DNS” (various SRE talks and blog posts)

An example of operational lore encoding rational Bayesian priors in complex systems—useful for grounding the essay’s discussion of heuristic triage.

Human Factors and Cognitive Limits

DeMarco, Lister (1987). Peopleware.

Foundational text on human and organizational limits in software work; supports the claim that bugspace is socio-cognitive, not purely technical.

Reason, J. (1990). Human Error.

Introduces models of error accumulation and latent failure that map cleanly onto multi-layer bugspace dynamics.

Socio-Technical Systems and Drift

Leveson (2011). Engineering a Safer World.

Explains how complex systems fail through interaction effects and organizational drift—highly relevant to epistemic drift and moving targets.

Allspaw, Hammond (2009). “10+ Deploys Per Day.”

SRE perspective on how feedback compression reduces bugspace by changing time regimes, reinforcing the observability and iteration arguments.

Yak-Shaving, Perfectionism, and Infinite Regress

Defines the phenomenon and provides the cultural backdrop for the essay’s more formal treatment.

Knuth, D. “Premature Optimization.”

Often misquoted, but relevant as an early articulation of how local perfection can derail global progress.

Nice, and accurate if a bit overtechnicalized.

Yak shaving has to me a dimension of having to find esoteric components to make a solution work - eye of newt, hair of yak beard - but it isn’t something one really wants to do. One does it because backing away means you have to climb way down the solution. Like, “Let’s use this new database because it is so fast!” And then after you’ve built code in dev, you realize it needs some oddball file system type on an obscure OS. You would have avoided the whole thing and just used Postgres if you realized this in the beginning, but maybe it just is worth it to get a razor, put on your boots and go find a yak. Maybe you are thinking of Bikeshedding?

“It works on my machine” might fit in here, where bugs are created / become evident when you try to deploy elsewhere. Cloud native dev goes a long way in solving this - the paradigm being, I can trust nothing so for every build I will start at the barest possible abstraction and build everything, every time.

The Linux “all bugs are shallow given enough eyeballs” is contra the principle of limiting debugging team size to retain context, although it seems to rely on the serendipity of finding the exact one person out of millions who actually has intimate experience with the thing.

Does one of the fancy-named debug techniques map to the old, delete all the code you wrote since last known good and add it back line by line until it breaks, technique?

i feel the first chart is missing "enemy action" or at least "nature intervening"