Principles for the Permaweird

Chiang's Law, Chor-Pharn's Law, Boyd's Razor

For February, the Contraptions Book club is reading Raiders, Rulers, and Traders: The Horse and the Rise of Empires by David Chaffetz, to be discussed the week of February 24. The chat thread is open for early comments.

I’ve been in Euclidean mode all week, by which I mean in a headspace where I’m constantly looking for candidate theorems, laws, conservation principles, paradoxes, and perhaps even axioms and postulates, for navigating the Permaweird.

We’re deep into a postmodern wilderness and we need to start imposing some authoritah on it. Making up Euclid-like elements for the strange new geometries we find ourselves in is a good place to start in 2025.

The last few years have been confused and chaotic, but I think we’re finally starting to see a good deal of very interesting lawfulness emerging in the contemporary environment. Strange sorts of lawfulness, but not confused chaos. There’s not yet enough for us compile something comparable to Euclid’s Elements, but we’re definitely underway now. The protocols of the future are starting to take shape. We can begin to navigate by coherent principles instead of relying on the mystical pronouncements of self-appointed seers. We can start testing and adopting systematic habits rather than letting heroic mythologies lead us over cliffs.

Let us delve into three of these elements. I’ve decided to become a professional delver for the age of AI.

Chiang’s Law

This week’s newsletter got delayed in part because I was busy writing another ambitious essay built around one such law, which I have named Chiang’s Law, after science fiction writer Ted Chiang who came up with the idea. I tried to reduce it to 12 words:

Science fiction is about strange rules, while fantasy is about special people.

I first came across this sometime last year, and I find it’s turning into an increasingly indispensable law to guide my thinking.

You can read all about it in the inaugural issue of Protocolized, a Substack magazine that I will be editing along with my colleagues Timber and Tim Beiko of the Summer of Protocols project. I wrote the inaugural issue essay, Strange New Rules, which talks about Chiang’s Law and lots of other stuff. The issue also launches a (free!) eBook of essays from our last two years of research, the Protocol Reader (one of my big editing projects last year) that you should load up in your Kindle and read right away. Several people (ht: Jenna D in particular) put a lot of work into this.

If we pull off our cunning plans, this is going to be a very interesting magazine. You should subscribe. Besides helping edit it, I plan to write one piece about protocols there every few weeks.

Related: I’ll be in Austin all next week, and co-hosting a week-long workshop (with pizza sponsored by the Summer of Protocols) devoted to Protocol Fiction. We’ll have bookend in-person coworking sessions on Monday evening and Friday afternoon, with online collaboration through the week. Sachin and Shreeda Segan will be hosting along with me. The goal is to start building up a pipeline of contributions and contributors for the magazine. Subscribe to the Protocolized magazine to stay informed of other such events elsewhere.

Chor-Pharn’s Law

Another law I posted about publicly this week is Chor-Pharn’s Law, named for my friend Chor Pharn (CP) Lee, mover-and-shaker of Singapore. CP shared it with me almost a year ago in a private conversation, and I find myself repeatedly citing it in my own private conversations, and using it as an analytical lens for an increasing number of political questions.

Here I didn’t need to do any compactification because CP’s original version is compact enough:

If you know who you are, you get a civilizational war, if you don’t know who you are, you get a culture war.

The law mostly applies to relatively sensitive matters where you don’t want to show your hand, so it is particularly useful for private cozyweb strategery conversations. But here is an example of me using it in a public conversation, in a note about current affairs in the US:

Chor-Pharn’s Law is a fine example of what we in the fledgling protocols science research community call a tension. It is a construct formulated as a tradeoff curve where different people will favor different positions, resulting in a structured conflict framed by the tradeoff. We call such conflicts engineered arguments, which is also one of the main definitions we use for what a protocol is.

You can delve more into tensions theory in the Protocol Reader. It is one of our research threads for the year in the program.

Boyd’s Razor

The last principle I want to offer you today is one I’m classifying as a razor, as in Occam’s razor. A razor is a decision rubric that has an element of paradox or counter-intuitiveness to it, and as a result is particularly challenging and costly to apply. This one is from one of my favorite thinkers, John Boyd, of OODA loop fame. But I’ll need to set the stage for it a bit.

Unless you’ve been hiding under a rock, you’ve probably noticed that OODA loops and Boydian maneuver warfare have gone mainstream in a bigly way. It’s no longer an obscure idea only military history nerds know about. It’s clearly the playbook Elon Musk deployed at Twitter and is now deploying at DOGE. Trump himself, in a less systematic way, has also been a lifelong Boydian actor. And I know for a fact that many people in (or associated with) the 2.0 administration are familiar with Boydian ideas and competent at formally deploying them. So it’s not an accident that unfolding current events look Boydian.

One sign: Several long-time readers I haven’t heard from in a while have suddenly reached out, wanting to chat about OODA loops and my 14-year-old book Tempo. These are topics I haven’t touched in a few years publicly, but here’s the slide-deck I used to use for workshops about this stuff. Maybe I ought to dust it off and update it for 2025 and offer it again.

Opponents of the Musk-Trump assault on the state capacity and machinery of the US generally seem to have no idea what’s hitting them, and seem to be assuming it’s just an amplified form of the noisy, disorganized, and ineffectual confusion that was Trump 1.0. In Chor-Pharn Law terms, they are approaching a civilizational war as a culture war. This time, the sound and fury do not signify nothing.

But the hapless opposition is beginning to get a clue that this time it’s different. This WaPo article (ht Renee DiResta) features a quote from an “education department official” starting to realize what’s happening:

“It’s an incredible snatch and grab blitzkrieg,” one Education Department official said. “We’re like the French in the Maginot Line on the border with Germany, and they’re like going around us through Belgium. They’re just … they’re so fast.”

I don’t want to delve into OODA/Boyd nerdery here (my quoted note above has a couple of pointers on how to apply it to current affairs), but I do want to point out ONE hugely important, arguably axiomatic, element of Boydian maneuver warfare theory that the Musk-Trump blitzkrieg is not following.

I’ll call this the Boyd Razor:

If your boss asks for loyalty, give him integrity. If your boss asks for integrity, give him loyalty.

This is the ONE element of the Boydian playbook that the Musk-Trump train does not, and ideologically cannot afford to follow. Loyalty-testing (which is the Right-Authoritarian version of doctrinal purity-testing in the Left-Authoritarian sense) is absolutely central to how they operate. It is the biggest shared element of leadership philosophy between Musk and Trump.

In the short term, ignoring Boyd’s razor makes the Boydian playbook radically easier and cheaper to implement. It just degenerates to “operate at a faster tempo” or some such over-simplification. But in the long term, ignoring Boyd’s razor creates a closed-off intellectual monoculture within the entity deploying Boydian strategies.

I’m a mediocre strategist at best, even in domains I know well, and I don’t claim to be great at running the Boydian playbook myself. At best I am able to support others with better warrior intuitions with some coaching. But the one piece I do try to always follow is Boyd’s razor. Even if I’m not doing all the re-orienting and fast-transients and tempo-control particularly well, I try to navigate the Boyd Razor well. Because a sense of your own integrity, once abandoned, is nearly impossible to restore.

Integrity is very easy to kill in a culture. You can simply tag people who dissent as traitors and fire them. You can intimidate people into loyalty. You can rope in the energies of a certain breed of extremely high-energy, high-IQ, but low-orientation grinder who will willingly pull all-nighters, put in 100-hour-weeks for years on end, and even go on suicide missions for you, either because they lack the aptitude for the moral reasoning Boyd’s Razor calls for, or are too young to have cultivated it, since it develops through morally demanding decision-making experience rather than smarts.

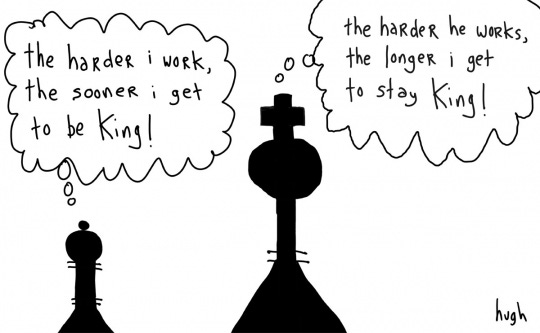

Why do people like Musk and Trump operate this way? It’s King logic, the essence of monarchist tendencies, as illustrated in this classic Gaping Void cartoon:

Boyd’s razor is the moral compass of Boydian theory, and monarchism is mostly about throwing it away by becoming a solipsistic self-certifier of your own truths. So loyalty becomes the same thing as truth, and integrity becomes a meaningless concept, since it can only exist in a pluralist context, where sometimes you give others the benefit of doubt rather than yourself. The pawn in this picture will never ever stop to ponder a loyalty/integrity question because they’ve surrendered that moral agency to the king. That is why they can work mindlessly hard with a “maniacal sense of urgency.”

Without Boyd’s Razor, you may win early battles with Boydian strategy, but you will descend into paranoia and increasingly vicious monocultural extremism and excess as you attempt to consolidate your position.

I’m no fan of what Musk-Trump are doing, so I’m happy they are ignoring Boyd’s Razor (and on a massive scale — their entire supply chain of talent is gated primarily by loyalty testing) and setting themselves up for eventual failure.

Respecting Boyd’s razor from Day 1 slows you down, and is generally costly — Boyd himself respected it absolutely, in how he treated both his own commanding officers and acolytes, and paid a heavy price for it. The better-known Boydian “do something/be somebody” fork is downstream of Boyd’s razor. The do/be choice only ever presents itself if you first navigate the loyalty/integrity moral maze successfully.

But paying the cost of following Boyd’s Razor buys you something. It builds up defensible positions steadily over time because it catalyzes pluralism, dissent, and openness to novel ideas. It fuels truth-seeking instincts rather than truth-manufacturing instincts. It prioritizes outcomes over theaters of appearance. It expands your coalition by learning from others, even adversaries, and co-opting them, rather than shrinking it into a cult. It allows you to keep the complete cycle of creative destruction going.

By contrast, ignoring Boyd’s Razor sends you down an intellectual cul-de-sac. The associated paradigm, no matter how powerful, eventually exhausts itself. Aside: this is why Musk’s “first principles thinking” is a fragile and questionable epistemic posture even when practiced sincerely. In complex systems, especially social ones, to keep things generative, you eventually have to deprecate some existing “first principles” and add new ones. And the main way you do that is by listening to high-integrity people whom you don’t immediately behead for disloyalty if they disagree with you.

Boyd knew this in his bones. That is why there is no canonical version of his ideas — he just kept tweaking his famous briefings till he died, and he expected his followers to continue tweaking them. Which they mostly don’t, resulting in Boydianism turning into an uncritical religion after his death. But Muskism has already turned into a religion — you can find several adoring, sanitized, and stylized documentations of his supposed playbook in formats ranging from Twitter threads to genuflecting biographies. This is not a good thing even for the legacy of a dead and buried thinker like Boyd. It is really damaging for a living thinker to be surrounded by such flattering mirrors.

The book we’re reading in the Contraptions Book Club right now, Raiders, Rulers, and Traders: The Horse and the Rise of Empires by David Chaffetz, explores a very revealing class of examples of how the Boydian playbook can go right and wrong depending on whether or not Boyd’s Razor is respected. While the Musk-Trump campaign in many ways resembles the campaigns of Genghis Khan or Timur, in an important way it does not: the most successful steppe nomad military campaigns appear to have respected Boyd’s razor.

I want to share two ideas isomorphic to Boyd’s Razor, because it is so important, it is crucial to internalize it in multiple forms, and to note that it keeps getting independently rediscovered.

First, in Richard Hamming’s classic, You and Your Research, we find a great metaphor for open-mindedness vs. close-mindedness: Whether or not you keep your office door open while you work.

Another trait [of great scientists], it took me a while to notice. I noticed the following facts about people who work with the door open or the door closed. I notice that if you have the door to your office closed, you get more work done today and tomorrow, and you are more productive than most. But 10 years later somehow you don't know quite know what problems are worth working on; all the hard work you do is sort of tangential in importance. He who works with the door open gets all kinds of interruptions, but he also occasionally gets clues as to what the world is and what might be important. Now I cannot prove the cause and effect sequence because you might say, ``The closed door is symbolic of a closed mind.'' I don't know. But I can say there is a pretty good correlation between those who work with the doors open and those who ultimately do important things, although people who work with doors closed often work harder. Somehow they seem to work on slightly the wrong thing - not much, but enough that they miss fame.

A big tell of whether you are an “open-door” type person is whether you tolerate a high degree of apparent inefficiency, interruption, and refractory periods of reflection that look like idleness. All are signs that your mental doors are open and are taking in new input. Especially dissenting input that can easily be interpreted as disloyal or traitorous by a loyalty-obsessed paranoid mind. Input that forces you to stop acting and switch to reflecting for a while.

Conversely, if you’re all about “efficiency” and a “maniacal sense of urgency” and a desperate belief that your “first principles” are all you need, you will eventually pay the price. A playbook that worked great once will stop working. Even the most powerful set of first principles that might be driving you will leave you with an exhausted paradigm and nowhere to go.

This is starkly visible when you analyze Elon Musk’s career. The “Elon Way” clearly worked brilliantly at Tesla (where I consulted briefly for one of his executives) and SpaceX. But it equally clearly did not work at Twitter. The acquisition is a financial disaster. The so-called “town hall” has degenerated into the court of a petty algorithmic tyrant who treats outbound links as marks of disloyalty. And a hugely valuable and important pluralist cultural institution, a veritable Library of Alexandria, got tagged as a stronghold of a manufactured “woke” adversary and burned down. That Musk subsequently made political lemonade out of the lemons he grew on the corpse of Twitter does not make it a success on its own terms.

Yet, talk to Elon loyalists, and they will refuse to acknowledge this failure and get into desperate contortions trying to paint X/Twitter as being as big a success as Tesla/SpaceX. Even bigger, if they’ve bought into his political ambitions uncritically.

Equally, talk to knee-jerk Elon haters, and they will refuse to acknowledge that despite all his problems, he did something very right at Tesla and SpaceX that is worth taking seriously and learning from. Even if it isn’t whatever his self-mythologizing emphasizes or his hagiographers highlight, he did something right. I have some conjectures about what that is, but I’ll wait till the full Elon arc plays out before theorizing.

Elon himself seems to believe he’s been equally successful at all three (if not in his smaller, more obviously speculative ventures). That his is an infallible Midas touch. One sign: he tweeted a meme image showing the Twitter episode as an obese figure wearing a “Twitter” t-shirt being peremptorily commanded to get on a treadmill, and being transformed into a svelte woman in an “X” t-shirt, with a parallel bit of imagery for what DOGE is up to.

Perhaps it’s just putting on a brave face, but I don’t think so. He appears to have genuinely convinced himself that the X chapter has been as unambiguously successful as Tesla and SpaceX. That it is worth repeating at DOGE. Why would such an obviously smart person develop such an inaccurate perception of himself and his track record? Isn’t it good to know where your behaviors are working vs. not?

He got there because he only asked for loyalty, and fired all those who only offered integrity in return.

This brings me to the second isomorphic idea, having to do with Steve Jobs.

It is useful to contrast Musk with Steve Jobs, whom he is often compared to. Jobs too had an autocratic, bullying personality. But he appears to have respected Boyd’s Razor. One senior executive who was close to him said that the way to succeed at Apple was “do the right thing, and make Steve happy.” In Jobs’ world, there was room for integrity to survive. Room for you to try and do your idea of “the right thing.” In Musk’s world, the razor has apparently degenerated to “Just make Elon happy; he knows what the right thing to do is.” (though it wasn’t always this way).

And it’s not about whether or not people can withstand autocratic, scary bosses who demand a lot and practice a sadistic management style. In many ways, Jobs was worse than Musk, for example in imposing a very secretive need-to-know communication culture instead of an open flow (10 points to Musk on that front). It’s about whether or not you can hold the excruciating moral tension of Boyd’s razor in your head. Jobs could. As far as I can tell, Musk cannot.

What truly burns people out is not that their boss is too demanding, hot-tempered, or even sadistic. What burns people out is not being allowed to exercise their integrity instincts. Being asked to turn off or delegate their moral compass to others. Plenty of people have the courage, the desperation, the ambition, or all three, to deal with demanding and scary bosses. But not many people can indefinitely suspend integrity instincts without being traumatized and burning out.

Another comparison. Jeff Bezos too has a reputation as a scary and demanding boss. I consulted for several years for an Amazon executive as well, and the public picture of what it is like to work there is basically accurate. But like Steve Jobs, and unlike Musk, Bezos too appears to respect Boyd’s razor. An important (in my opinion the most important) management idea at Amazon is “disagree, but commit.” A principle that allows people, especially very powerful and senior people others might be terrified of, to systematically accommodate high-integrity dissent. When you hear an idea from a smart, weaker person that you don’t agree with, but bet on anyway, that’s a disagree-but-commit move. Everybody can occasionally work up the courage to disagree with a scary boss in a fit of healthy-minded integrity, but rarely is it a systematically encouraged tendency. If you reliably call them stupid and fire them while they are quivering before you under the stress of doing what they think is the right thing under hostile conditions, a certain process of elimination of all integrity gets underway.

At Amazon, the disagree, but commit principle is supported by another one: great leaders are right… a lot. It takes the confidence that comes from being right a lot to be able to tolerate and underwrite risks being taken by weaker underlings that you don’t necessarily agree with. That is in fact how you build up courage in others, and make them “right… a lot” in turn. In fact, all of what I saw of Amazon management culture seemed consistent with Boyd’s razor.

This is one reason I never wrote off Blue Origin the way many people did. That company had problems of course, but it did eventually manage to get to orbit with the first try, with a big rocket, which is a truly remarkable thing. I know nothing about the internals of the company, but I love the motto, gradatim ferociter. Step-by-step, ferociously. A motto that says you’re prioritizing thoroughness over efficiency at least some of the time. It’s a playbook that takes much longer to run, more tortoise than hare, but involves fewer things blowing up along the way. The more you deal with human systems, the more important it is to be thorough rather than efficient (it’s called the Hollnagel’s ETTO principle, and an upcoming essay in Protocolized by Timber will tell you all about it).

We’ll never be able to truly test this counterfactual, but I think the Twitter saga would have unfolded better with the gradatim ferociter playbook, because it is a nearly pure people-system. DOGE too would have worked better with a thoroughness-oriented gradatim ferociter playbook, but again we’ll never know. Musk has Trump’s ear, not Bezos.

And finally, to connect all this to my current obsession, steppe nomad culture, the difference between Genghis Khan and Timur, and the reason the former left behind a relatively long-lasting 3-generation empire (even if in multiple shards) while the latter’s empire unraveled immediately, is that Genghis respected Boyd’s Razor and Timur did not.

Boyd’s Razor is going to slit the throat of many otherwise brilliant strategists who don’t think a costly moral compass that prices integrity over loyalty is worth paying for and installing into your operations.

They will deserve it.

One of the few tactics employed by Musk-Trump opponents so far that has had even a whiff of effectiveness has been the effort to turn the two against one another. I'm referring to things like the visa debate and the "President Musk" quips. Both of these have a "Boydian Razor" logic to them because they short circuit the partnership between the two. There is a strong tension between the two megalomaniacs that is currently being managed, but if there is a way to derail the current Trump-Musk train, pushing on their "Boydian Razor" failure points seems to be one approach with potential.

Thought provoking as always Venkatesh. I wonder where time fits into Boyd’s razor? In order to respect Boyd’s razor you have to have the patience to tolerate integrity and wait to see how things play out. Musk also seems to focus on shorter time horizons / rapid gratification over the last few years. I am still processing the ideas here but think time is an element that is critical here too..