The History and Future of Memeing Things Into Reality

Introducing Slotraptions, AI-assisted textual contraptions

Opt-in section of the Contraptions Newsletter devoted to backgrounders, notes, and experiments cooked up with AI assistance. Serving up elevated slop 1-2 times a week. Recipe at end. If you only want my hand-crafted writing, you can unsubscribe from this section.

In early 2021, a ragtag group of Reddit users sent Wall Street into a frenzy by memeing a struggling video game retailer’s stock to unimaginable heights. What started as an inside joke about GameStop shares suddenly became very real: the stock’s price skyrocketed 1,700% in weeks, toppling hedge funds and minting overnight millionaires. It felt as if an internet meme had escaped cyberspace and manifested in reality – a triumph of collective belief over financial “fundamentals.” This wasn’t the first time, or the last, that belief and imagination have bled into the real world. From ancient myths to modern marketing, humans have long tried to “meme things into existence,” willing ideas to jump from our heads into the tangible world.

This feature explores the curious history – and uncertain future – of this phenomenon. How have propaganda, occult thoughtforms, and sci-fi concepts blurred the line between fiction and reality? Can collective belief truly reshape the world, or are there hard limits to wishing something into being? We’ll tour a rogue’s gallery of reality-bending concepts – from egregores to hyperstitions – and see how they map onto today’s meme-driven culture. Then we’ll examine the sobering truth behind the magic: why some fantasies crash into the brick wall of reality.

Many Names for the Power of Belief

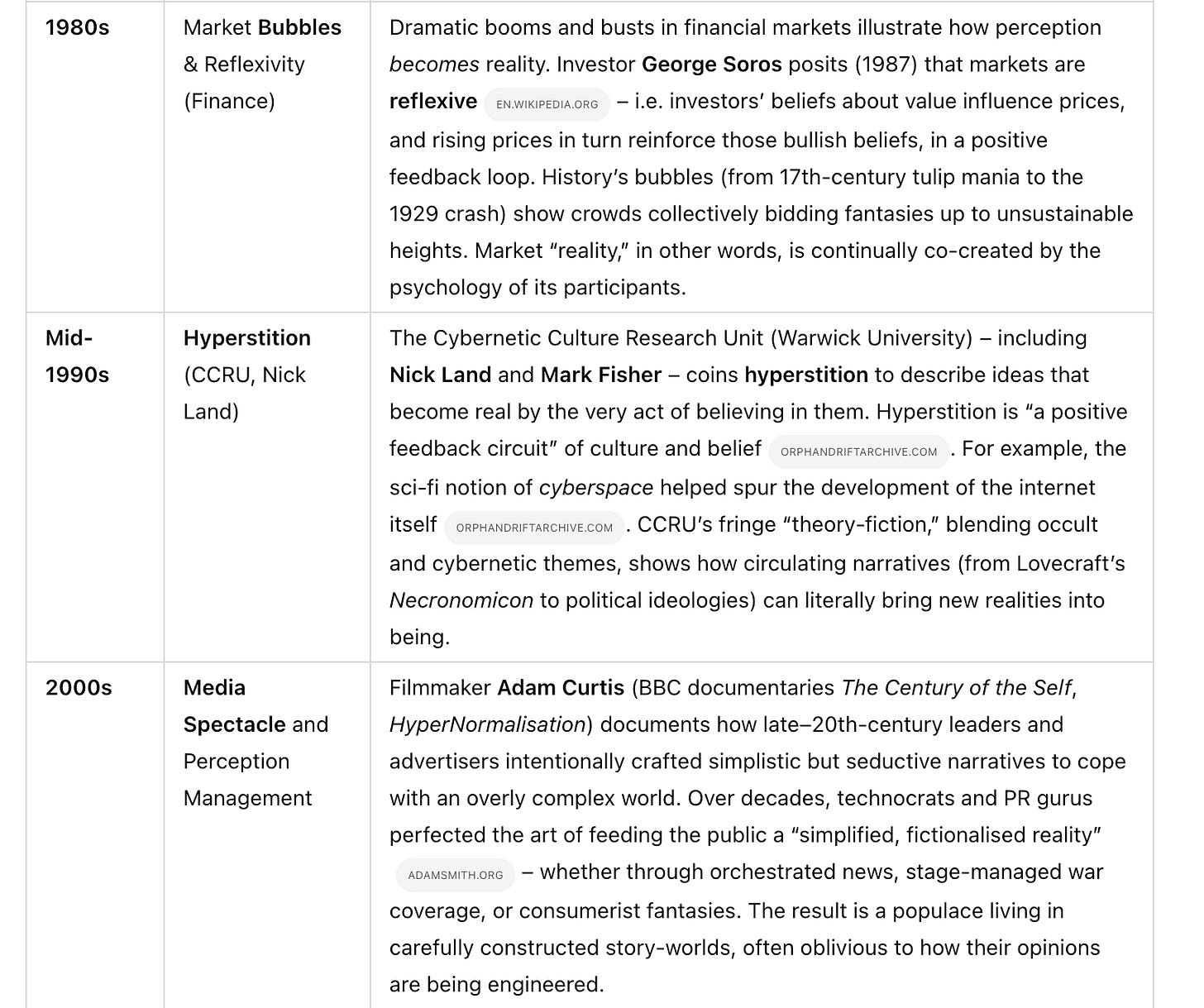

Across cultures and eras, people have given names to the idea that imagination can become real. To ground our discussion, here’s a quick tour of key concepts and terms related to reality-making by belief (and where they come from):

Notably, Philip K. Dick serves as a patron saint of this topic. Though not an occultist or social scientist, his science fiction anticipated a world of synthetic realities. In a 1978 essay, Dick observed how modern society is bombarded with “pseudo realities manufactured by very sophisticated people using very sophisticated electronic mechanisms” (brainyquote.com, brainyquote.com)

Decades before deepfakes and algorithmic filter bubbles, he was warning that the fake can become indistinguishable from the real. His influence echoes in contemporary discussions of simulated worlds and information warfare – whenever we talk about “living in a simulation” or “post-truth reality,” we’re walking in Dick’s footsteps. It’s fitting that his definition of reality – the part that doesn’t go away when belief does – serves as a reality check for all these grand ideas of meme magic.

From Propaganda to Tulpa: A Brief History of Willed Reality

The urge to manifest ideas isn’t new. Long before we had image macros and Reddit forums to pump stocks, we had rituals, rumors, and rallies – ancient and analog methods of memeing things into existence.

Propaganda, for instance, can be seen as an early 20th-century “reality distortion field.” In World War I, governments learned that controlling the narrative could rally entire nations. By World War II, propaganda had grown so powerful that it fueled everything from the Nazi myth of an Aryan utopia to the Allied spirit of democracy. When Bernays wrote in 1928 about “minds molded” and “ideas suggested” by unseen manipulators (commonsenseethics.com), he was pulling back the curtain on this very magic trick: convince people that X is true (through posters, radio, film), and lo – eventually X becomes true in the sense that people act on it en masse. A populace convinced that “the enemy is monstrous” will fight all the harder; consumers convinced “this product will make you happy” will hand over cash. The idea moves from propaganda office to public mind to physical reality.

Older still is the mystical route to reality-making. In many spiritual traditions, belief itself is a force. Take the Tibetan Buddhist concept of the tulpa, a spiritual entity or “imaginary friend” conjured entirely from disciplined thought. Monks believed that with enough focus, a mental image could attain temporary reality – at least in the mind of the creator. Western occultists adopted and adapted this idea in the 19th century, blending it with notions of group magic to birth the concept of the egregore. If one holy man’s thoughts could summon a phantom, imagine what hundreds of people believing together might do. Occult circles in the early 1900s treated egregores as serious business: think of them as DIY gods or guardian spirits assembled out of collective will. While skeptics scoffed, even skeptics must admit that less mystical versions of this happen all the time. Consider national identity: a nation is in a sense an egregore – an invisible entity (the “nation-state” or its spirit) that’s very real in its effects only because millions believe in it. Money, too, is arguably an egregore: those colored pieces of paper have power because we all agree they do. In these ways, society has been play-acting reality into existence for ages.

Modern pop culture has its own breed of collective conjurations. Fan communities sometimes joke about “manifesting” something into reality – say, willing a cancelled TV show back on air by sheer hashtag power. This sounds fanciful, but it occasionally works. When enough fans make noise (a concentrated belief that “this show deserves to live”), studios take notice and – poof – the show returns, as if the collective wish incarnated it. In darker fashion, conspiracy theories can act like memetic viruses that create real chaos. The more people believed the QAnon conspiracy online, the more real-world impact it had – culminating in actual crowds showing up at rallies and even the U.S. Capitol, driven by what began as an internet “fiction.” A completely false narrative can yield tangible consequences if enough people devote themselves to it. These are egregores of the digital age: crowdsourced fantasies that step off the message board and into the streets.

Hyperstition: When Fiction Hacks Reality

If occultists use the language of magic for collective belief, modern theorists use the language of coding and feedback loops. Hyperstition is a key idea here – essentially the art of making reality behave like a writable program. Coined in the 1990s by a renegade philosophy collective, the term hyperstition means a self-fulfilling prophecy that deliberately makes itself real. Unlike a superstition (passive false belief), a hyperstition is an active cultural hack: spread the idea far and confidently enough, and the idea pulls itself into being.

One oft-cited example is cyberspace. In 1984, author William Gibson coined “cyberspace” in a sci-fi story, envisioning a vivid digital world. The term caught on, inspiring researchers and entrepreneurs. Money and talent poured into making networking tech cooler – more like Gibson’s vision. Within a decade or two, we had something eerily akin to true cyberspace: the internet and VR worlds millions now inhabit. The fiction became fact, guided by people who, consciously or not, chased the fiction (orphandriftarchive.com). Nick Land describes this as “culture as a component in a positive feedback circuit” (orphandriftarchive.com) – a loop where imagined futures inspire actions that create those futures. Science fiction authors have inadvertently (or intentionally) been hyperstition engineers: from Star Trek inspiring cell phones to Isaac Asimov’s robots inspiring real robotics research.

Finance is another arena extremely sensitive to hyperstition (orphandriftarchive.com). Markets often run less on hard reality and more on perception (stories, expectations, memes!). If enough investors believe “X stock will go up,” their buying can make it go up – the belief becomes true. We saw this with the GameStop saga: the narrative of a “meme stock” rally brought in real buyers in droves, which drove the price up and validated the narrative. It’s a reflexive loop: believing makes it so. Startups in Silicon Valley similarly thrive on hyperstition—“fake it till you make it” is practically a creed. Entrepreneurs pitch grand visions (sometimes vaporware), garner investment through hype, then use the funds to turn the hype into reality. As long as everyone acts as if the dream is real, it edges closer to becoming real. This is hyperstitional alchemy at work in everyday business.

Even politics has flirted with hyperstition. Some commentators described the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign as powered by “meme magic,” where online communities earnestly believed they could influence outcomes through memetic warfare (think of the cult of KeK and the frog meme). It sounds bonkers – magical thinking at its finest – yet those communities did generate viral messaging that arguably shaped perceptions. The election result itself (to them) felt like conjuring a frog-faced chaos god into the White House via shitposts. At the very least, it proved that in the age of social media, the line between joking about reality and changing the reality is thin and weird.

However, as potent as hyperstition and memetic manifesting can be, there’s always that Philip K. Dick quote lurking in the background: “Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.” After riding high on the power of belief, one eventually asks – what doesn’t go away? What is the bedrock that stubbornly resists all our wishing? This brings us to a much-needed reality check on meme-made worlds.

The Limits of Memed Reality

Belief can be powerful – but it is not omnipotent. Philip K. Dick’s definition of reality reminds us that there’s an objective world still humming along regardless of our memes and dreams (brainyquote.com). In contrast to hyperstition’s success stories, many attempts to meme a new reality run headlong into an immovable truth: wishing doesn’t make it so, not always. This section looks at those cautionary cases – where collective belief failed to reshape reality, or created only a fleeting illusion that eventually crashed.

Dick’s maxim could be the tagline for every financial bubble in history. In a bubble, everyone believes an asset is worth ridiculous sums, and for a while that shared delusion makes it seem true – prices skyrocket. But when confidence cracks, reality reasserts itself with a vengeance. The Dutch Tulip Mania of 1637 is the classic example: at its peak, speculators paid fortunes for a single tulip bulb, convinced the value would only go up. It was a hyperstition in action – until the bubble burst and rare tulips turned back into…just flowers. Belief alone couldn’t suspend economic gravity. Modern markets have seen similar frenzies: the dot-com boom, the housing bubble, Bitcoin’s wild swings. Each time, a narrative catches fire (“this will go up forever!”) and enough people believe it that it temporarily becomes reality in pricing. Yet eventually, most of these assets come crashing back to Earth when hard fundamentals (profits, supply and demand, physical utility) don’t justify the faith (investopedia.com. As one investment columnist quipped, “stocks returned to Earth once the moonshot stories ran out of fuel”. The 2021 meme stocks exemplified this: GameStop, AMC, and others soared on pure memetic enthusiasm, but many latecomers who held on to the dream ended up nursing heavy losses when those shares plunged back to realistic levels (studocu.com). Reality, in the form of cold math and economics, doesn’t go away just because a Reddit thread fervently believes otherwise.

Likewise, social or political movements driven by memes can find that belief isn’t enough to overcome material and structural forces. The Occupy Wall Street protests of 2011 brimmed with genuine passion and the belief that a new social order was imminent. The slogan “We are the 99%” spread like wildfire (a meme of economic justice), and for a moment it felt like the sheer moral force of that idea would rewrite laws and topple plutocrats. But in the end, Occupy fizzled without achieving its concrete aims – a poignant case of a memetic high encountering the inertia of political reality. It’s not that the idea died; it influenced discourse for years to come. Yet the actual structures of finance and government proved far less malleable than a trending hashtag. Memes can raise awareness and shift culture, but turning that into lasting policy change is a tougher alchemy.

Physical reality is the hardest limit of all. No meme can make gravity disappear. A million people chanting that the Earth is flat will not flatten the Earth. We can create communities who act as if a lie is true (flat-earthers exist), but their belief doesn’t alter the planet’s shape one inch. This seems obvious, but it’s worth stating: material facts have a way of being stubborn. During the COVID-19 pandemic, various factions fiercely believed conflicting realities – some thought the virus was a hoax, others treated it with extreme seriousness. Unfortunately, the virus didn’t care what anyone believed; it infected and killed based on epidemiology, not ideology. In a clash between meme and molecule, the molecule wins eventually. Similarly, a conspiracy theory might convince followers that “drinking bleach will heal you” – and tragically, if they try to live in that memed reality, the actual chemistry of poison prevails.

Even our cleverest new reality-bending tools encounter limits. Advanced AI language models like ChatGPT can produce shockingly realistic text, often blurring fact and fiction. They sometimes “hallucinate” – confidently stating false information as fact (ibm.com). For a moment, the reader might believe the AI’s fiction. But outside the AI’s synthetic reality, the real facts remain unchanged. An AI can insist, say, that Alexander the Great won the Battle of Waterloo – a completely made-up claim – yet no history book will update to match the AI’s story. AI hallucinations highlight how convincing an invented reality can look, and yet how quickly it falls apart against actual evidence. The internet is littered with such mirages that vanished on closer inspection.

Modern finance and tech gave us perhaps the perfect parable: cryptocurrency. For a while, the fervent belief in certain crypto projects was their reality. Tokens with no tangible product reached multibillion-dollar valuations purely on memetic buzz (remember Dogecoin’s rally to the moon?). But when the enthusiasm evaporated, many of those coins crashed to earth, some near-zero, as investors realized there was little of substance underneath (kirrmar.com). The most dramatic example was the collapse of the FTX crypto exchange and its associated token in 2022 – a high-flying venture fueled by hype and star power that imploded virtually overnight, wiping out billions. The crypto world learned that while “we’re all gonna make it” was a fun meme, math and fraud eventually caught up with them. In Dick’s terms, blockchain reality was that which didn’t go away when the promotional tweets stopped.

All these cases drive home a simple truth: belief needs reality as a partner, not a victim. Memes and collective enthusiasm can nudge reality – sometimes impressively far – but if they venture too far from factual grounding, reality snaps back. The stock must eventually reflect the company’s earnings (or lack thereof). The movement must contend with laws and institutions. The body politic, the laws of physics, the supply chains – those continue when the hashtag campaign ends or the bubble pops.

None of this is to pour cold water on imagination. Rather, it’s a reminder that the alchemy of memed reality is tricky. As much as ideas can shape the world, the world also shapes which ideas survive. We can bend reality with memes, but we can’t fully break it. And knowing those limits is part of mastering the art.

Conclusion: Reality, Remixed but Not Replaced

So, can we meme things into existence? Yes – but not effortlessly, not permanently, and not always in the way intended. History is full of instances where collective belief moved mountains (sometimes literally: the building of pyramids and cathedrals surely required a shared fervor, an egregore of purpose). Our digital age has supercharged this ancient magic, letting memes spread faster and farther than ever. A joke on a forum can spawn a global movement; a fantasy from a novel can become an everyday technology. In a very real sense, reality is part construction – made by our agreements, stories, and perceptions.

Yet for every triumphant hyperstition, there’s a crash to reality that follows. It turns out the universe has a sense of irony: the more we chase our fictions, the more we eventually appreciate the non-fictional ground under our feet. Perhaps the sweet spot lies in between – a future where we consciously harness collective imagination to improve the world, while staying humble about the facts of that world. We might not be able to wish away gravity or conjure free money, but we can rally people around powerful ideas and even birth new entities (communities, innovations, cultural shifts) through belief and persistence.

In the end, memeing things into existence is less like casting a spell and more like telling a really persuasive story – one so compelling that people act as if it were true, until it becomes true. We are the storytelling animal, and those stories can indeed walk off the page. The caveat is that reality is the editor who gets the final cut. As we venture forward, dreaming up the next big meme to change the world, it’s wise to keep Philip K. Dick’s razor in mind. Build castles in the air, yes – but remember to check if there’s ground beneath them. Reality will always have the last word, and oddly enough, that’s what makes the game of memeing reality so fascinating. After all, if it were easy to bend the real world to our will, where would the fun (or the challenge) be in that?

Recipe: Initial high-level ChatGPT 4o brainstorm around lighthouse concepts and history I already knew about, followed by a few Deep Research iterations. Deep Research had an issue where each iteration was like a new first draft rather than an incrementally improved nth draft. It would lose stuff I wanted to keep in the process of adding stuff I wanted added. So this version I’m sharing is a cut-and-paste Frankenstein monster from multiple iterations. Had to screenshot the core table since there was no easy way to cut and paste it cleanly. Final text has some cosmetic formatting edits, but is otherwise untouched, and unchecked beyond basic high-level scan.

Acknowledgement: A lot of my prompting and massaging here was shaped by what I’ve learned from Renee DiResta (author of Invisible Rulers) and Sarah Perry (who introduced me to egregores and various related concepts). Both were frequent contributors on these topics on my old Ribbonfarm blog.

Very cool

Share a prompt or two?

Did you seed with your corpus (or whatever we’re calling that now)?