The Societal Machine

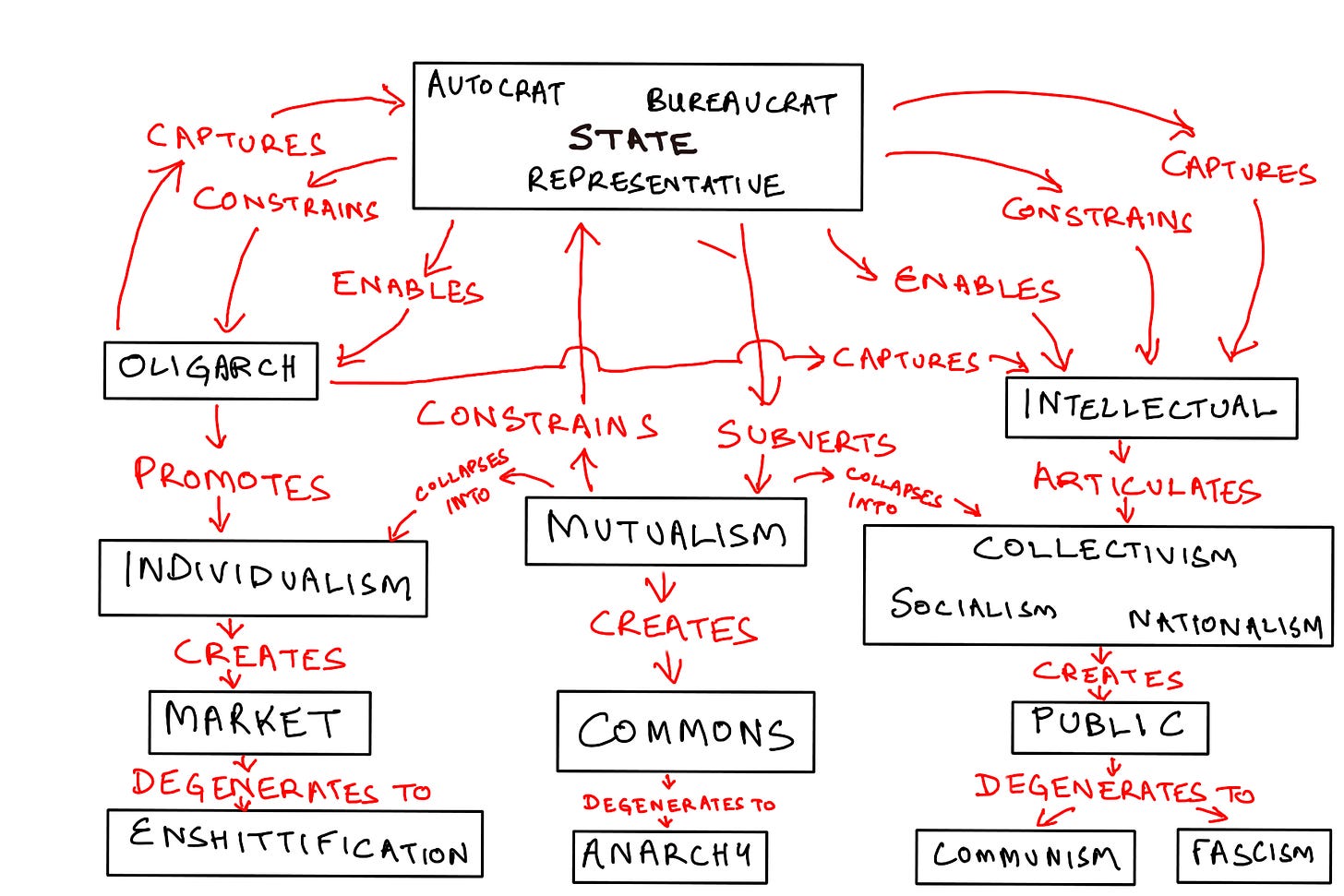

A diagram that explains everything

This research note is part of the After Westphalia series.

I’ve been in an engineering mood lately, spending more time building Lego Technic models and robots than writing. Which makes me predisposed to treat the topics I’m thinking about as machines to assemble and analyze rather than essays to write. One such topic is the nature of a (the?) commons, and its relation to mutualism as a human condition. I made this diagram to capture how I think these work within a larger “societal machine.” It’s not particularly innovative; just a cleaned-up and merged version of models implicit in various extant political theories from all four corners of the political compass.

From an engineering perspective, this is not a very good machine. But it is the one we have. It is not capable of sustained, stable operation. Instead, it is liable to degenerate to one of the four bad states at the bottom as it winds down. At which point you get a revolutionary, often violent reset to different initial conditions (but not a different machine). I used to think democracies lower or eliminate the need for revolutionary resets but now I suspect they mostly just reshape the frequency/amplitude spectrum.

The natural and preferred but unstable human condition is mutualism, which is liable to collapse into either individualism or collectivism (which has two major flavors) through the catalytic effects of two kinds of actors who are simultaneously enabled and constrained by the state: Oligarchs and intellectuals. Along with the human constituents of the state itself — autocrats, bureaucrats, and elected representatives — they form a subset of humanity that sees itself as irreversibly alienated from the main body politic, and inclined to drive it away from the threatening mutualism condition. These five actors (autocrats, bureaucrats, representatives, oligarchs, intellectuals) typically constitute the “classes” as opposed to the “masses.” All five actors are present in every real society, whether or not they’re formally acknowledged or legitimated. This is why the Selectorate Theory model (in Dictator’s Handbook) works fine whatever the nominal image the society holds of itself. The classes can be mapped to the interchangeables, influentials, and essentials in that model whether it calls itself a communist state, a liberal democracy, a theocracy, or a monarchy.

The masses can be in one of three states: individualism, collectivism, or mutualism (which is an unstable entanglement of the other two). In these states, they constitute markets, commons, and publics respectively (these are notionally pure states that usually actually exist as a mix). Here I’m using all three terms to refer both to human conditions, and to the constructions humans in those conditions place upon resources in their environment. So resources can be in market (“capital”), commons, or public states, and can be exploited/stewarded/regenerated in corresponding distinct ways. The difference between the latter two is that public resources need a state to govern, while commons resources can self-sustain to a significant degree so long as they’re not the target of active capture attempts (ie, they have a certain amount of natural hardness that makes them somewhat resistant to the tragedy of the commons in the face of low-intensity free-riding etc). Formal distinctions between of private and public property in a legal sense is not particularly important in my model. If it’s not a commons, the logic of the Dictator’s Handbook dictates how resources are managed.

The masses only have real agency in the mutualism condition. In the individualist condition, oligarchs shape their behaviors through economic incentives to constitute legible and well-governed markets, and in the collectivist condition, intellectuals shape their behaviors through ideologies to constitute legible and well-governed publics. In both these conditions, the illusion of agency is stronger than actual agency, and therefore “awakening” of a political consciousness (via “pills” to use the modern metaphor) to this reality is possible (but not necessarily consequential).

A pill is a trigger that creates a realization of the degree to which our behaviors, in particular shared, habitual behaviors, are a result of the covert actions of other actors we haven’t been paying much attention to. The habitual aspect provides predictable leverage, while the shared aspect allows for economies of scale. The threat of administering pills is the main weapon intellectuals have against the other four kinds of actors that constitute the classes.

The classes can be described as actors who achieve their ends by shaping other people’s habits en masse (hence the common sheeple metaphor). Those who allow their habits to be so shaped constitute the masses. Membership of the “classes” is partly a matter of ascriptive status markers, privileges, and inheritances, but mostly a matter of resistance to having one’s behavior shaped covertly by others (political “awakening” of any sort, however, is neither necessary, nor sufficient for this). Mutualism exists when such resistance is both widespread and effective, rendering the formally designated classes weak or irrelevant. In contrast to revolutionary action, mutualism ephemeralizes rather than dismantles the classes, as a side effect of the masses simply exercising relatively higher agency over their own behaviors. This results in any habits being less stable and predictable, and shared to a lower degree. This makes mutualism less friendly to en masse exploitation with economies of scale, through either markets or publics.

A fragile, artificial sort of mutualism can arise as the result of political awakenings triggered by conflict within the classes, but can also arise from factors such as the inhospitability and instability in the environment, or the hyperlocal variety and temporal variability in adaptive survival knowledge. The latter varieties of mutualism tend to be more robust and sustainable, and tend to have a “punk” disposition. Artificially induced mutualism tends to be fragile because it lacks a natural source of variety and temporal variability to draw upon to sustain itself. So as homogeneity — across individuals and across time — reasserts itself through mimesis and intellectual activities, so does covert control. To use OODA loop terminology, mutualism is individuals in entangled, frequently re-orienting OODA loops that are hard (in the sense of computationally costly) to get “inside” of en masse. Political influence can still be exercised by the classes in strong mutualist conditions, but it is just much costlier, and does not scale well.

The mutualist condition is not a “public” in the modern sense. A public is a degenerate, collapsed state of a mutualist condition marked by the presence of stable, widespread habitual behaviors. Publics have a certain predictability and homogeneity that is partly consciously constructed, partly a result of degeneracies and homogeneity in the environment.

Here I am using Corey Robin’s definition of a public as something an intellectual creates through the force of ideas. In my current thinking, both public and market are degenerate collapse states of mutualism, and neither is particularly preferable to the other. They reduce full humans to citizens and consumer-producers respectively, which are both degenerate conditions. See my earlier essays The Descent of the Public and Reimagining Publics for the evolution of my thinking about publics. This essay is a non-trivial update to my thinking there.

A disambiguation note — Hannah Arendt’s notion of a public corresponds to a putatively stabilizable version of what I’m calling mutualism, as opposed to the more common modern understanding of a public, which is much closer to Robin’s notion. Arendtian publics are a nice idea but I don’t think they’ve ever actually existed historically. The examples in her writing (such as Ancient Greece) seem idealized to the point of romanticism. Robinian publics on the other hand, seem realistic enough. They are an artifact of modern mass media and clientelistic representative democracy, which allowed for the authoritarian high-modernist legibilization of the masses through the force of ideas. This mechanism did not meaningfully exist before the 16th century. The closest thing to it was traditional organized religion (which factors across bureaucrats and intellectuals in my model), which has not been dynamic enough to act decisively on technological modernity. The work of modern intellectuals is essentially the crafting of transient new religions that can create workable modern publics capable of moving at the speed of modernity. Traditional religion, by contrast, tends to slow the speed of modernity down to the speed of religion.

Mutualism in this conceptual machine is the only force that can meaningfully constrain the state, and the state is therefore disposed to subvert it. In the short term, the state is largely indifferent to the specific alternative condition (individualism or collectivism) mutualism collapses to, since both are more easily and profitably governed than mutualism. This is why the Dictator’s Handbook model works so well, regardless of the type of state. So long as the masses are deactivated as a live and intelligent political force, by being either atomized or aggregated into declawed anonymity, the rest is details you can be largely indifferent to if you’re part of the classes. What combination of markets and religions you use to govern their behaviors is irrelevant so long as the governance is cheap enough. It is the behavioral uniformity and predictability of the masses that matters, not the specifics of the behaviors.

There is an asymmetry in the diagram though. You’ll note that the capture arrows only flow left to right, where by capture I mean taking over hearts, minds and souls at an adjacent organizational locus, without disrupting or taking over the explicit organizational and functional logic of the target. Oligarchs can capture states and intellectuals. States can capture intellectuals. Intellectuals can’t capture anything but they can foment violent revolutions (with “pills”) against the other two capture forces. States can’t intellectually capture oligarchs (since the logic of economic production is too rich to capture without destroying), but they can throw them in jail, kill them, or nationalize their property.

This asymmetry means oligarchs have a slight advantage so long as things remain in a non-violent/non-revolutionary mode. Their mechanisms of influence are likely to drive things towards atomized individualism and markets. This is one reason the intellectual classes typically tend to ally with state actors rather than oligarchs, and administer more collectivist than individualist pills to the masses.

A final note: Even if mutualism doesn’t collapse sideways into individualism or collectivism, it does have its own natural degeneracy pathway, towards anarchy in the popular sense of the word, as a stressful state of violent chaos. I use the term in this sense in the diagram above, not in the wishful theoretical sense anarchist intellectuals repeatedly try and fail to popularize. The masses instinctively (and correctly) recognize that without strongly favorable environmental conditions — such as mountainous terrain for example — mutualism will degenerate into anarchy in the sense of a stressful state of chaos, and that this state may not be preferable to being governed as markets or publics.

This is why, despite the obvious attractions of stable mutualism, and the problems with the collapse states/pathways on either side of it in the diagram, the machine as a whole does not seem to change much historically.

The one huge factor that seems to slowly but surely change this is technological evolution. It is in the nature of technology to add more variety and variability to the environment than homogeneity. The long industrial age was in some ways anomalous, transforming technological potentials into societal uniformities. This historic trajectory is in the process of reversing itself, since computing technology tends to add heterogeneity faster than it adds homogeneity. If this is indeed happening, we should see the environment becoming more conducive to mutualism in the long run.

We have all elements of the machine present today. We know what happens when some elements are forcefully collapsed, as when there is an attempt to exclude markets in collectivism, or rely on the kindness of strangers in mutualism.

Capitalism seem to be dependent on both technology and the size of the market more than expected. My commentary is that the oligarchy maybe an ephemeral artifact that will be incorporated into the market as the market participation grows.

Is open source software an obvious example of mutualism creating the commons? What are some older examples? Has mutualism largely expanded or stayed the same over past thousand years?