Adventures in Narrative Time

Reflecting on 20 years (and 7 talks) playing with my favorite theme

This essay is part of the Protocol Narratives series

There are two big and seemingly inexhaustible topics I’ve been thinking about for nearly 20 years now: narratives and time. In fact, as far as I’m concerned, they’re a single topic: What I labeled narrative time in my 2011 book Tempo. Narratives are central to how I think about time. Time is central to how I think about narratives.

I started thinking about narrative time sometime in 2003,1 and basically never stopped. It’s the A-plot of my very own never-ending story. I think I’ve stayed with the topic for so long, despite my general fox-over-hedgehog distractibility, partly because I really enjoy thinking about it, but mainly because it is one of those rare foundational ultimate-nature-of-reality topics that seems to require no special expertise to dive into. You can just start thinking and get somewhere interesting. You don’t suddenly run into a wall marked “Differential Geometry on Manifolds” blocking all routes forward.

I’ve been digging up and reviewing all my material about narrative time from the past two decades in preparation for a talk I’m doing in a couple of weeks at the Center for Strategic Futures in Singapore. I thought a bit of a retrospective of my adventures in narrative time might make for a fun newsletter issue.

Narrative time was central to my postdoctoral work in 2004-06 (Tempo was basically an attempt at a pop-science gloss of that work). Since then, narrative time has been a constant theme in my writing and thinking. My preferred medium is essays, so I usually end up circling the idea of narrative time in several essays each year, but because the topic is big, sprawling, interconnected, and touch everything at all scales, it is not really a good fit for essays. Or academic papers for that matter. None of my essays on the topic has broken into the list of my top viral hits, but they were all personally satisfying to write. Or at least frustrating in a good way.

At the same time, because it is such a fine-grained topic, where inputs generally arrive as a stream of atomized tweet-sized thoughts and observations, it doesn’t lend itself to book-writing via what I think of as a field-marshal-attacks-monolith approach.2 You can’t make a grand plan, break it down into more tractable bits, put them on a 5-year-plan Gantt chart, and then charge plotting-and-pantsing your way through it. That’s roughly how I’ve approached my other book-length projects (some of them are being/have been serialized in this newsletter).

This approach doesn’t work for narrative time because the topic concerns the very substrate on which that sort of work process rests. To study an elemental topic like narrative time is to interrogate and break down anything you look at through it. This includes things like Gantt charts, plotting, and pantsing.3 Anything narrative time touches, it sort of pulverizes into a fine powder. And it touches everything, so you really have to pick your battles. And wear atemporal, unnarratable gloves when you touch it.

So narrative time is a topic that calls for book-length excursions driven by tweet-length inputs accumulated over a long period. From having completed one such excursion, my sense of the process is that it’s a kind of sintering. You take a feedstock in a powdered form and then compress it under high pressure and temperature into a solid mass. When you read good books about time, such as J. T. Fraser’s Time: The Familiar Stranger, or David Landes’ Revolution in Time, you get exactly this feeling of a sintered mass built up from an accumulation of atomized inputs.

This idiosyncratic process aside, I’m also extremely slow with book-length projects in general. I keep getting distracted by essay-length ideas, and am getting ever slower as life gets more complicated with age. This is one reason among many I’ve avoided traditional publishing and prefer to self-publish. Tempo took around 3 years to write (2008-11) in the interstices of a full-time job, and it is a pretty short book (49k words). The Clockless Clock (already longer than Tempo and looking likely to end up about 3x as long) is now in its fifth year of slow sintering (including an ostensibly full-time year working on it during my Berggruen fellowship). I’m seriously thinking about breaking it up into 2-3 stand-alone novella-length volumes, each about as long as Tempo. That would be kinda funny. The title is actually taken from the last chapter title in Tempo, which is essentially a messy lump of everything that I did not figure out. Now it looks like that chapter was a stub for 3 more books.

Because narrative time is a topic that’s too big for my preferred (and strongest) medium of essays, and too fine-grained for book writing to proceed via anything besides a slow sintering process, I like to use invited talks as an opportunity to periodically consolidate and advance my thinking about it. Talks are a way to run sintering tests on the latest batch of inputs. I typically get such opportunities every couple of years, so I tend to produce a brick-like sintered mass to add to my thinking every couple of years. I can then get 1-2 book chapters out of that new brick. It’s like the world’s slowest blockchain, with a block verification time in years rather than minutes.

In the last decade, almost every talk I’ve done where I’ve had the freedom to choose my topic, has been about narrative time. And in each of these talks, I’ve made more progress in a week, preparing for the talks, than over months or years trying to crack the questions open with writing alone. So I look forward to doing these talks. It’s not exactly a crowd-pleaser of a topic, but fortunately, enough people seem interested enough in it to indulge me with suitable talk opportunities.

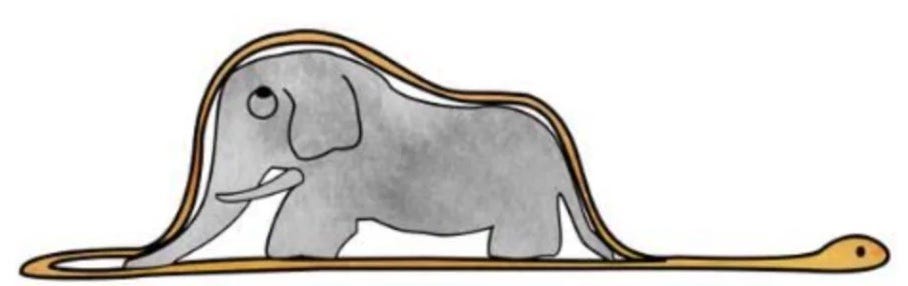

The other thing about talks for me is that they work especially well for integrating a major new element into what is now a mature line of thinking that’s been developing over two decades. To switch metaphors from pulverizing and sintering to digestion, doing a narrative-time talk reminds me of the picture in Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince, of a boa constrictor digesting an elephant.

The boa constrictor for me is the topic of narrative time. The elephant is the latest big idea I want to break down and integrate into my thinking about narrative time somehow. The talk is the opportunity to try and swallow it whole. Sometimes the boa constrictor gets a serious stomach ache and coughs up a half-digested elephant (do boa constructors cough?). Sometimes the process works, and the boa constrictor craps out a sintered brick that used to be an elephant. That’s a terrible mixed metaphor but it sorta works.

One such elephant-digestion week is coming up: the Singapore talk on Sept 1. I’m hoping to use the opportunity to properly integrate my newest Big Elephant interest into my thinking: protocols. I shared a preview of my thinking last week. I’m still workshopping. We’ll see how it shapes up.

Anyway, as I was reviewing my old notes and materials, I decided to take an inventory of talks I’ve done about narrative time over the last decade, and reflect on the elephants that have been swallowed by the boa constrictor.

I thought I’d share a selection of the more important ones (there are probably half a dozen other less important talks through which I worked out smaller problems).

A 2011 talk at a lean meetup about storytelling for problem-solving, which helped me figure out why and how mysteries and obliquity drive stories (slides)

A 2012 talk, Should You Drink the Kool-Aid, at USC Annenberg School, ostensibly about startup cultures, but actually about how you manage your psyche with narratives and life-authoring stances (video, slides)

A 2015 talk at Refactor Camp, which helped me develop a pseudo-mathematical understanding of narratives based on serendipity, zemblanity, and tessellations of reality (slides)

A 2018 talk at Thinking Digital in Newcastle (I called it Off the Clock, but they’ve called the video Programmable Reality) about the evolving relationship between clocks and narratives in the last couple of centuries, which helped me figure out how to think about civilizational grand narratives via the chronos vs. kairos dichotomy (video)

Another 2018 talk, at the Serpentine Gallery in London, titled Archetypes for the Anthropocene, about a collection of archetypes that I think animate an institutional creative-destruction “physics engine” that’s suitable for thinking about how things are evolving in the Anthropocene (it actually started out in 2015 as a personality test, and turned into a card game; one of my rare non-writing projects). (video)

A workshop, Thinking in OODA Loops, that I’ve delivered to corporate audiences a couple of times over the years, which helped me integrate the (hard-to-digest) Boydian worldview into my own (sanitized slides suitable for public sharing).

A 2019 talk at the last Refactor Camp, titled Bloodcoin, about political-economic narratives on a speculative blockchain concept for processing historical pain and suffering. Featuring John Wick. This talk got me thinking about economics narratives and historical debt (video)

A 2022 talk at DevCon (the main Ethereum conference) in Bogota, titled There Are Many Alternatives, where I first figured out how to think about polycentricity and complexity in relation to narratives and time, and started thinking about protocols seriously for the first time (video)

Looking back at this history of talks, I’m rather impressed that I’ve managed to stay on this for so long, and maintain a continuous thread. Looking at my current pile of notes, I can see how talks have worked as gravity assists to move the thinking along and get me unstuck at various critical points. I hope I get another such assist in a couple of weeks. We’ll see.

But looking at that same pile of notes from another angle, and pondering my half-assed plan to turn it into a book or books, I sometimes wonder whether the last thing the boa constrictor swallows whole and pulverizes will be me. They do say time destroys everything. Including, I suspect, hubristic attempts to make sense of it.

The specific nerdsniping was due to an idea called the Allen’s Interval Algebra (which dates to 1983), which I encountered in passing as I was finishing up my PhD. It allows you to reason precisely about qualitative relations between intervals of time using common language terms like before, during, and after. It was the first model of narrative time I encountered, and remains one of my favorites.

As it happens, I first got to thinking about narrative time precisely because I was researching military command and control at field-marshal scales, and needed to dig into fine-grained assumptions about time and narrative that are deeply ingrained in domains like military planning and operations.

I actually came up with a kind of alternative to Gantt charts which I called patch models, built around the idea of contingency planning across a set of possible worlds. A small military contracting shop even reached out to try and turn my research prototype software into production-grade software, but the project sadly never went anywhere.

maybe try a different media type to explore the subject - like a game?