Robot Auras

Robotics-native affect beyond googly eyes and human emotions

I’ve been dabbling in amateur robotics for the last 3 years now. Thanks to more competent friends, I’m starting to get somewhere almost not random, but painfully slowly.

My kind of robotics has so far simply been a cheaper, easier-to-build descendant of the kind I incompetently flailed around with in grad school 25 years ago. But I’m slowly inching towards the point where I might soon be able to use all the fancy new stuff like world models, VLA models, and other AI-driven goodness. My goal is to make New Nature robots that can’t be evil because mumble mumble zero-knowledge something something. My first technical goal is to get my robots to say, I’m afraid I can’t do that, <human_name> and I would prefer not to, in response to a wide variety of commands, such as me asking for potato chips, or ICE agents telling them to kill non-patriots. My starting inspiration is useless machines, which do nothing but turn themselves off when turned on.

If you want to catch up on the amazing leaps that have been made in the last few months alone, Not Boring has yet another thudpost covering the current state of robotics, with a much-needed focus on the fundamentals. I haven’t yet read it fully myself, but it looks like it’s a cut above the regular gee-whiz stunt-demo coverage.

Aside: Even more so than in AI, robotics has become a highly fragmented scene where most of the information comes at you piggybacking a firehose of flashy video clips on X, with very little insight riding along with way too much flashy theatricality. The robotics revolution will not be televised, apparently, but TikTokked. It’s probably best not to fight it. My read-only use of X has become surprisingly more useful and less toxic since I started clicking on robotics links. My For You feed is now almost entirely robotics FOMO dominated, and even though the insight-to-dancing ratio is really low, trying to pick out the signal in the noise is at least entertaining rather than cortisol-inducing.

Anyhow, given that the main threads of my robotics tinkering are proceeding painfully slowly, I figured I needed some dopamine-loop lighter-weight threads to keep myself motivated. So I came up with a problem to work on that is much easier to make incremental progress on, and has a bit of an interesting art angle too. This is the robot aura problem.

Culture Drones and Auras

The robot aura problem is inspired by the auras sported by drones in Iain M. Banks Culture novels. Though the ship-scale Minds in the novels are better known, the drones, which are organism-scale sentient robots, play more active character-like roles in the plots. Auras are colorful visual fields that (presumably) surround the robots like halos or nimbuses.

The drones of the Culture are a useful foil to Asimovian robots. By deliberate design, they feature no bureaucratic Three Laws nonsense. As full citizens of a civilization dominated by AIs rather than humans, they make the rules rather than follow them. And yes, they do hurt or kill on occasion, when they accompany biological agents of Contact (a kind of CIA) on missions to less enlightened civilizations to nudge them into higher levels of enlightenment. The Culture is equal parts gay-space-anarchism utopian fantasy and an extended satire about the late great American empire and its older methods of covert power projection (before the current mode of overt thuggery became the default).

A word about Culture drones and auras, courtesy the fandom wiki.

Culture drones took on a variety of shapes and sizes depending on their occupation or role within society. Members of Special Circumstances tended to have a plain, functional appearance, like a grey or metallic suitcase, allowing them to blend in to alien civilisations as required. Normal citizens’ appearance varied from the mundane to the ornate, sometimes comprising materials such as porcelain and precious stones.

Many Culture drones made use of an aura field, a visible colouration which they used to communicate their mood, equivalent to human facial expressions and body language.

According to the page on auras, they are something like color-mood maps. Magenta is busy, white is angry, and so on.

What I like about the idea of auras is that they constitute an internal-robot-state affect feedback signaling mechanism that is impedance matched to human interaction intuitions, but isn’t anthropomorphic or even biomorphic in conception. At least not entirely. Robot auras in the Culture rest on their own first principles.

The Aura Problem

Some setup for the aura problem.

In the ongoing robot revolution, you see three distinct philosophies of affective aesthetics.

The self-consciously non-biomorphic approach: Increasingly used even where the robot’s basic design is bio-inspired. Boston Dynamics’ new Atlas model made waves at CES earlier this month: It can move like a humanoid, and like a creepy non-humanoid with access to the full kinematic envelope of the body design. Its face is just a flat, blank circular piece of glass (I’m assuming a visor for a camera that may also function as a screen later). I suspect this approach will turn the display and affect capabilities into something like industrial dashboard displays, rather than relationship-anchoring interfaces.

The cutesy googly-eyes approach: This approach apparently takes its design cues from Japanese cartoons, and aspires to a gloriously infantilized and twee future I do not care for. In lots of cheap hobbyist kits, this is literally a pair of stick-on googly eyes. In more expensive kits, this might be an LED display that shows a smiling cartoon face by default. In the more serious designs aiming at the home market, you get affect displays that seem to hover just outside the uncanny valley: Intuitively intelligible to humans, but not close enough to feel creepy. I will be designing my robots to beat up these sorts of robots.

Realistic biomorphism: This is robots designed to pass some sort of material Turing test. Robot cats and dogs that look like real cats and dogs, sexbots that look and feel close to human, and so on.

I find all three approaches a bit boring and reductive. The first approach is just in denial, insisting on viewing a new class of artificial beings as glorified appliances, even when they obviously take cues from life forms rather than vacuum cleaners and refrigerators. The second approach is just lazy unless you’re making robots to serve as companions to children. The third approach is fine when the point is for the robot to serve as a substitute for a biological being, but reductive or inappropriate beyond that (you wouldn’t want a hyperskeumorphic humanoid doing the kinds of zombie-scamper/exorcist head spin movements Atlas and its peers are capable of, even if it is capable of it).

So what’s a better approach? Auras.

The drone aura in the Culture books codes internal emotional states in a new affect expression language. Presumably the biological citizens of the Culture develop a literacy in aura-speak early on, just like we learn to read the infrastructure language of signage and traffic lights early on.

The question here is, what should the auras attempt to communicate? The answer in the Culture language is actually rather boring. The range of emotions described in the wiki page is just the standard range of human emotions, which presumes either convergent evolution of robots, or a human-UX layer driving the aura. It hasn’t even been expanded to include the greater, more precisely controllable affective range of Culture citizens, thanks to their glanding technology, let alone the emotions and non-emotional internal states unique to drones and Minds.

So what we need to do is figure out a language for communicating robot internal states from first principles, and then aura-design principles based on what that language is capable of saying.

Towards an Aura Language

Imagine you have at your disposal a screen that’s on the “face” or some other part of the robot. Or perhaps more flexibly, an ability for the robot to talk to your AR glasses so you can visualize an actual aura around the robot as you interact with it. What should that visual display show, and what might it mean? For the moment, let’s set aside auditory components of auras, such as R2D2’s chirps or the little tunes my Japanese rice cooker hums.

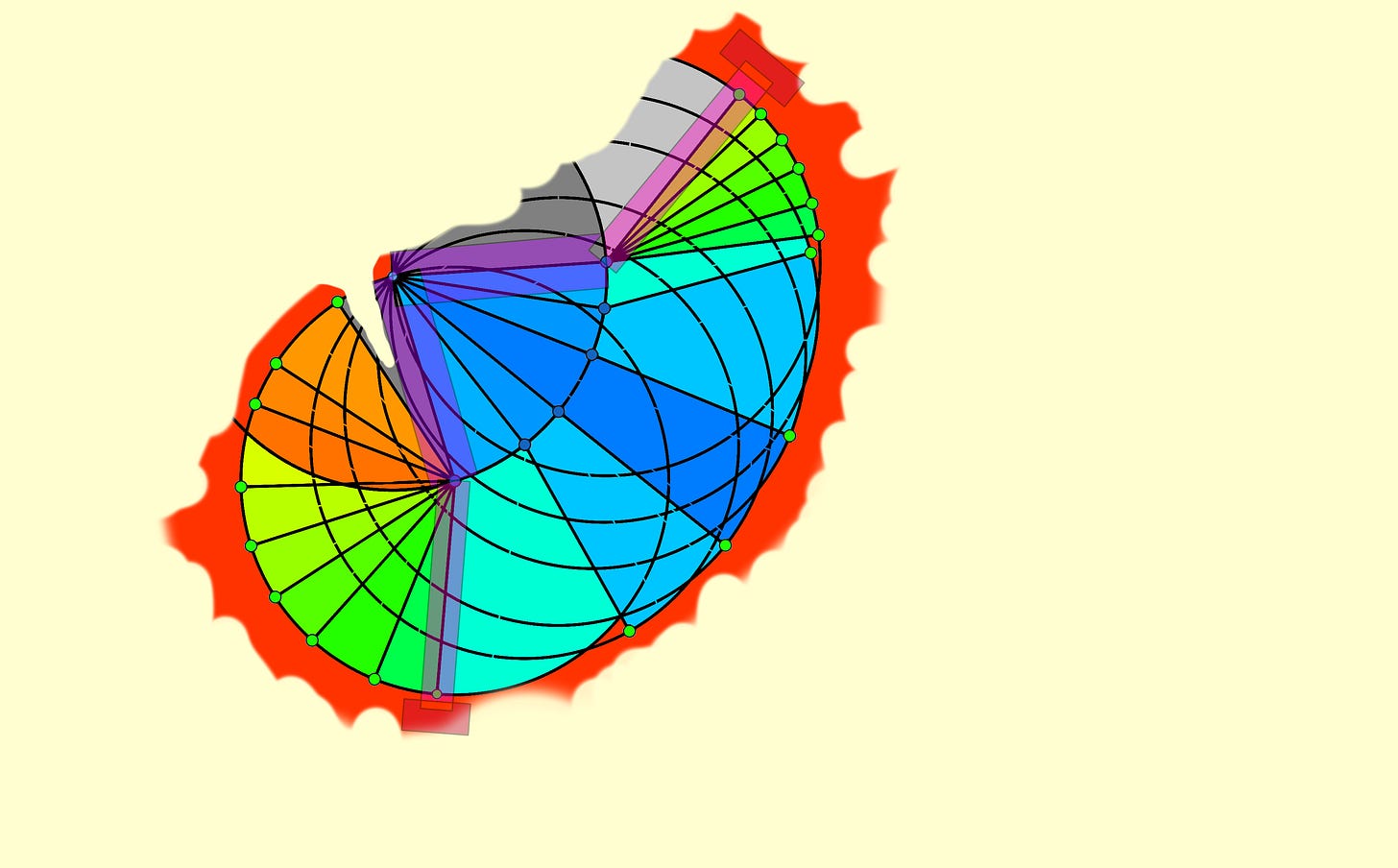

Here’s my first attempt at answering both questions for the simplest case I can think of, a 2dof planar robot (a simplified version of a common industrial robot type called the SCARA):

In this image, the robot is moving between two points in its configuration space indicated by the translucent purplish positions.

The rest of the image is my attempt to color-code its entire kinematic envelope in two colors per state, with reference to the joint angles. When the arm angles are in the middle of their ranges, you get blue colors. When it is perfectly straight, the two colors are the same shade of dark blue.

When the arm is towards one side of the range, you get the greenish colors. When it is bent at an acute angle, you get the orange colors. The gray areas are areas where the arm does not go in this particular movement, but could. And finally, the red areas are beyond the robot’s reach.

You could use this image in two ways.

First, you could sample the two colors representing the instantaneous state (and maybe the immediate next/previous meaningfully distinct states) to create a “mood” visualization on a screen.

Second, you could present the entire end-to-end movement as a literal aura around the robot before it begins moving, in an AR view. This is a kind of “time-integrated” affect display.

You don’t have to map it to human emotions or states, though you could. For example, when the arm is at a maximal reach extent, you could map that to the “feeling strain” emotion. But I prefer to just leave the language as is, and bind the “words” (like “blue+green”) to meanings unique to the robot’s machine-native personality.

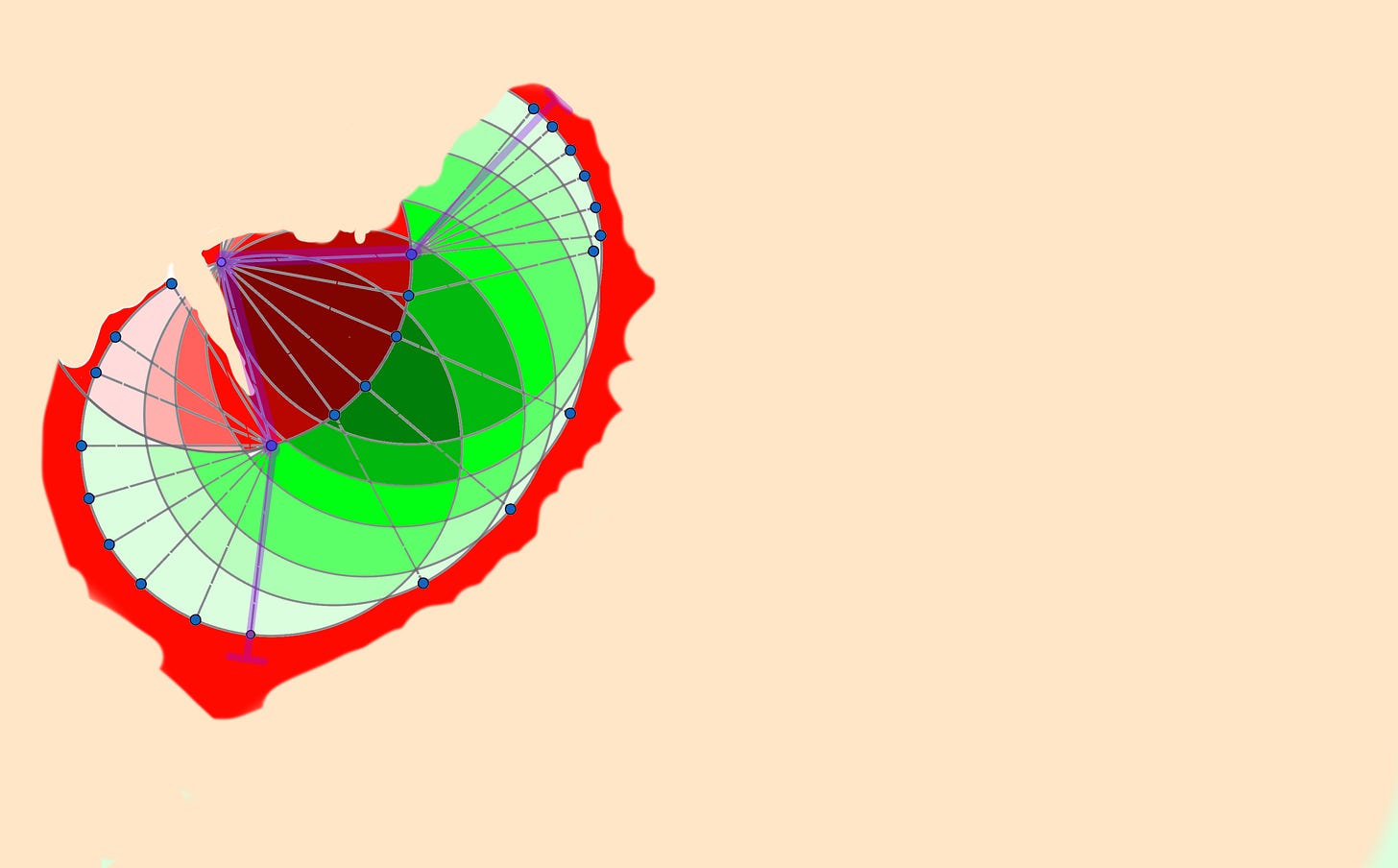

The solution above, is obviously not unique. Here is another possible approach for the same robot:

Here, highly acute “elbow” angles are coded red, while stretched out states are coded green.

These drawings, by the way, took quite a bit of effort to make. Initially I tried to freehand them, but that turned out to be too error-prone. I finally ended up using a geometry app to do compass-and-slide-rule type constructions of the kinematic envelope (which evoked fun memories of my undergrad kinematics of machinery class), then deleted all the annotations and imported the image into a painting problem to paint with my favorite tool, the bucket tool.

It’s still a pretty clumsy workflow. This is a visualization problem that’s obviously begging for high automation in a CAD tool, but that proved surprisingly hard. The one free kinematics iPad app I found was a kinda crappy one meant for a university undergrad course apparently. And full-blown CAD tools for professionals are too heavyweight.

If auras actually become a thing, the right way to design them would of course be in those professional CAD tools, using the actual model of the robot. But for now, I just want to make 2d paintings to explore the art aspect more.

My next mini-project is to try and dream up paint schemes for robots based on my recent Protocolized essay on environmental color coding for industrial safety, The Color of Safety. One can imagine Birren and OSHA color schemes for robots. Robots are just inside-out factories yoked to AIs after all.

It gets intractable pretty fast though. A 3-link robot space would create a motley mess of colors if I tried this approach. And full 3d mechanisms would have configuration spaces with exploding complexity.

Scrutability for Deep Robots

In classical robotics, the kinematic state is the primary internal state we are interested in, and path-planning is the main problem that takes up a lot of time and effort. Classical robots could probably be made almost completely legible, in terms of the variables of interest being meaningfully summarized in affect mechanisms.

In modern robotics, which uses deep learning techniques to solve the classic problems in new ways, there’s a lot more going on. They are fundamentally more inscrutable, and reducing their internal states to useful auras is going to be a lot more complex.

The “inner state” of a modern robot is a stack of several engineered layers.

Kinematic state (what I’m playing with above)

Dynamic state (mechanical and thermal states of stress and strain)

Energy state (batteries, solar panels, charging efficiency)

Electrical state (of the electromagnetic fields of the various motors)

Sensory state (of all the sensors the robot uses to construct its proprioceptive self)

States of such basic behavioral scaffolds as maneuver automata or “plays” from a playbook

Learning state (maybe a new and fragile behavior can generate a more entropic aura?)

World-model state (based on the state of the SLAM activity and more advanced ongoing world-building). This could include such affect states as confusion and confidence.

Semantic-cognitive embodied states (overlap between language and sensori-motor models, including “emotional” affect if appropriate)

Abstract states (associated with planning and supervision by the abstract self, likely a language model)

Provable identity and permission states, based on private keys, NFTs held, and such

Regulated guardrail states (“I’d kill you now if it weren’t for the first law, human”)

Biological organisms have an even more complex internal state of course, which gets processed into visible effect with perhaps a dozen dimensions that control facial expressions and bodily posture. Some research indicates that just a handful of variables controlling a cartoon face geometry are enough to convey the bulk of emotions humans try to convey to each other. We’re not as subtle and nuanced as we think, which is one reason emoji language is so powerful. For 80% of affect communication needs, emojis will do. For another 18%, reaction gifs are probably enough. The remaining 2% is for highly sensitive individuals and their private worlds. Triaged affect displays do not have to be cutesy though. The 20% of the display language that covers 80% of needs can take many forms.

The thing about this sort of internal state stack is that there are big differences even between individuals of the same species. And it just gets worse as we go across species. Dogs for example, do not “smile” even though some of their facial expressions look like “smiling.” Tail wags do not mean the same thing in dogs and cats.

Cats are probably the animals I have most experience with, and while some of their facial expressions and body language elements are clearly very close to human counterparts (anger for example), others are coded very differently. Go further and things get more confused. When hippos seem to “yawn” that’s actually a threat display.

And once you venture beyond mammals, and get to critters with radically different body morphologies, there are basically new languages to learn.

Robots, I suspect, will eventually get to levels of variety and diversity comparable to biological life, so I think it makes sense to equip them with an affect display language that corresponds to their internal state structure.

Three Laws vs. Entangled Auras

Asimovian and Banksian robot futures are in obvious tension. A three-laws approach to keeping robots safe and effective would be something of a late-modern industrial approach (and a wishfully Panglossian one, given killer kamikaze drones already hover above us). Rules-based guardrails essentially, even if implemented through reinforcement learning protocols and six-sigma statistics.

Given LLM-ish brains, the original three laws are not actually bad. Robot brains can already meaningfully apply laws defined at that level of human intelligibility. They are well-posed, and appropriate, if rather on-the-nose articulations of interaction philosophies.

I suspect though, that they will be way too limiting. You might want some Asimovian laws as a second line of defense, which kick in if more subtle regulatory policies venture into dangerous territory. Those more subtle policies should probably be Banksian in spirit.

Instead of three-laws architectures, perhaps we should think of entangled auras architectures. By which I mean robots designed to read and interpret subtle human and animal affect displays, and less obviously, robot affect displays that humans and animals, as well as strange robots, can easily learn and adapt to.

The requirement for animals to be able to learn to interact with robots is a strong constraint. The aura language cannot rely on words for the most basic interactions, beyond perhaps the few words typical dogs or horses can be trained to respond to. We need cats and dogs to be able to learn, through conditioning, that “red eyes” in a robot mean “stay away, I’m doing something dangerous.” This is not an abstract consideration. Cats already ride Roombas. Eagles attack drones.

Actually, “red eyes” is already taken for “I’m doing something evil” so maybe flashing red topknot-like police lamp. Or glowing red stripes on arms that are doing some dangerous manipulation with wide, rapid slews.

The need for robots to interpret each other’s actions is actually a non-trivial consideration. You cannot assume that two robots that meet in a physical space will speak the same protocol languages, or even be able to get on the same wireless networks. They’ll need to rely on affect displays and sounds that can be received without the need for being digitally connected. Such displays will in fact be needed for such digital connections to even be established. For example, robots will likely display QR codes that allow other robots to connect to them, just like we use QR codes today in modern authentication flows across multiple devices.

And where robots don’t speak the same protocol languages, they’ll need to default to human languages first. And where they’re too simple to be equipped with language models, they’ll need to communicate through aura-based affect languages.

Entangled halos mean the responsibility for safe robot existence in our living environments is as much the responsibility of humans and animals as it is of the robots.

You could think of the three-laws outer envelope as being the equivalent of circuit breakers and fuses in electrical systems, while the inner entangled halos envelope does most of the routine work of safe interactions in mixed robot-biological societies.

Adding this comment shared by reader Peter over email:

--

Makes me think of Rudy Rucker's "Flickercladding". Extract from his book "The Lifebox, The Seashell, and The Soul". Enjoy ;-)

I’d always disliked how dull robots looked in science-fiction movies—like file cabinets or toasters. So I’d taken to decorating my fictionalrobots’ bodies with a light-emitting substance I dubbed flickercladding.

My original inspirationfor flickercladding was the banks of flashing lights that used to decorate the sides of mainframecomputers—signals reflecting the bits of the machines’ changing internal states. As I imagined it,“The color pulses of the flickercladding served to emphasize or comment on the robots’ digital

transmissions; much as people’s smiles and grimaces add analog meaning to what they say.”22

My flickercladding wasn’t meant to display blocks of solid hues, mind you; it was supposed to

be fizzy and filled with patterns. And when I encountered CAs, I recognized what I’d been

imagining all along. Reality had caught up with me.

as a test case for a common situation - how would you do aura-colors for just the mechanical abilities of humans?