The Gramsci Gap

System emergence in monstrously morbid interregnums between worlds

The Contraptions Book Club is currently reading City of Fortune by Roger Crowley, to be discussed the week of January 27.

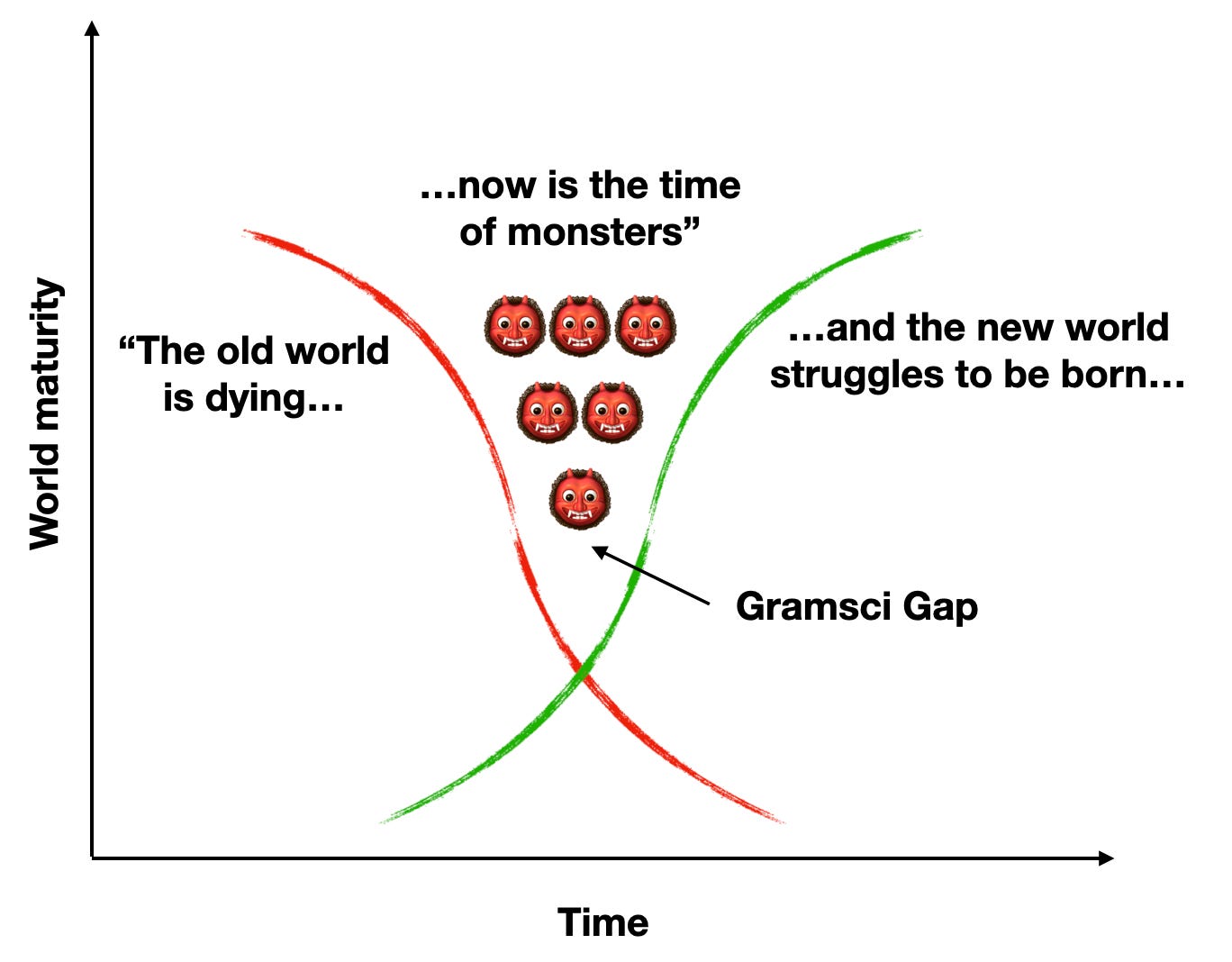

You’ve probably heard some version of the Gramsci quote “The old world is dying and the new world struggles to be born. Now is the time of monsters.” Here is a picture I made of the idea. I’m going to call this “time of monsters” the Gramsci Gap.

The line is generally attributed to Antonio Gramsci, but this particular version is actually a loose translation by Slavoj Žižek. A tighter translation of the original, according to a footnote in this essay, would be “…in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.” This last bit, in either form, is not usually included in the quote, but to me it is the most interesting part. It makes an otherwise vacuous thought interesting.

Žižek’s version, with “Now is the time of monsters,” captures the spirit of the original, but perhaps loses some of the useful specificity. Interregnum suggests a particular understanding of old and new worlds as regnums — reigns of particular systems of governance rather than material circumstances or environmental epochs. The Latin regere is at the root of English words for both governance, like reign and regime, and words for measuring and ordering, such as regulation1 and rule. The word ruler is particularly interesting since we use it both for a measuring stick and a monarch (which was also true of the original Latin apparently). This is not a coincidence. Measurement and control go together. The human ruler doesn’t just make the rules while remaining above them, he is also the measure of the rest of humanity.

The point of this little etymological digression is that the word interregnum could refer to either the period between the fall of one monarch and the rise of another or to the period between the fall of one system of rules and the rise of another. Most often, it refers to both, because it takes both to make a world in the sense of a regnum.

So “appearance of morbid symptoms” and “time of monsters” could apply to either aspect of world. Gramsci, being a jailed communist in fascist Italy, likely had both in mind, since he’s best known for a version of Marxism that emphasizes the importance of hegemonic system narratives over the specific depredations of ruling classes. This is a robust and general distinction. Modern Marxists for example, transpose this idea from class to race, and make a distinction between racism in personal attitudes and structural racism embodied by institutions. Conservatives reject this particular move, insisting on the rationality of their favored institutions, but simultaneously make similar distinctions with regard to (for example) the personal characters of individual muslims versus the institutional dispositions of Islam the religion (which they might characterize as “structurally terroristic” or something).

Without taking a position on any specific example, I will take this distinction as sound and given in general terms — every regnum has both rulers and rules of consequence and substance, and reasonable accounts of the Gramsci Gap must comprehend both aspects.

If you put the two translations together, you get an interesting idea that a “monster” is an instance of “morbid symptoms” appearing in either or both of the two building blocks of “worlds” — systems of rules and special people.

Carl Schmitt’s famous definition, “sovereign is he who decides on the exception” is useful for gluing these two kinds of monsters together, but I will be overloading it here to apply beyond sovereigns in the monarchial sense.

A human monster in the Gramsci Gap is typically any individual with some degree of exception-making capability, who is using that capacity in monstrous ways, resulting in one class of morbid symptoms.

A systemic monster in the Gramsci Gap is typically some scheme of rule of law that has undergone late-stage monstrous perversions (going beyond what I’ve been calling paradigm exhaustion recently), resulting in a different class of morbid symptoms.

What can we say about these two kinds of monsters and the conditions they create in the Gramsci Gap?

In any societal system, within some broad band of normal operating conditions, there are always some individuals with some degree of Schmittian sovereignty. In a sufficiently complex system, the presence of discretionary exception-making roles is normal.

Classically, these individuals are understood to be singular monarchs “at the top,” of both the social and functional hierarchies that define the architecture of the society in question, and “above the law.” In practice though, Schmittian sovereignty is unevenly distributed all over any given polity, whether it is a rule of law polity where nobody is above the law, or a rule by law polity, where some are formally above the law. I used to be more enamored of this distinction, but I’ve come to see it as irrelevant. Exception-making agency exists in any real system.

Besides de jure sovereigns, there may be powerful oligarchs and nobles who are “too big to fail” and therefore accommodated in special ways, unaccountable bureaucrats operating under principal-agent hazard conditions that afford them de facto Schmittian sovereignty, “anarchs” in Ernest Jünger’s sense (“an anarch is to anarchy as a monarch is to monarchy”), judges operating within a messy tradition of case law with weak constitutional coverage, and outcastes or outlaws at the margins too weak and insignificant to bother governing. Each kind of exception-maker may also face consequences beyond the law of course. Monarchs can get deposed and executed. Bureaucrats can get purged. Individual anarchs can get lynched. So there are risks to being an exception-maker, but the point is, the system needs exception-makers to function.

Exception-making authority in any sufficiently complex system is necessarily highly distributed, even if the shape of the distribution varies. In fact, the shape of the distribution is a good proxy for the system’s complexity.

So what does it mean for the exception-making to exhibit morbid symptoms?

Morbid Exceptions

There are three archetypes of morbid sovereign exception-making capacity, at three typical societal loci.

The first, of course, is the classic mad emperor at the top (Trump and Putin being textbook contemporary examples) and unaccountable oligarchs (Musk is turning into one) driving systems into what engineers call anomalous excursions.

These familiar archetypes are well-studied, and they may enjoy a great deal of literal “above the law” protections, either de jure (Trump) or de facto (Musk). What makes them “monsters” is not their mere existence or special status, since they exist in all systems at all times, and are usually even celebrated for “normal” use of their Schmittian sovereignty. It is the appearance of morbid symptoms in the Gramsci Gap that turns such archetypes into monstrous versions of themselves.

A mad emperor is one who makes mad exceptions, and there are too many examples in history to count. My favorite is Muhammad bin Tughlaq.

A mad oligarch is one who uses Schmittian leverage to commit entire societies (rather than just their private affairs) to potentially ruinous paths without consent. Historically, these have been rarer because it takes technologically complex societies to throw up mad oligarchs, and there are typically too many other people with counter-capabilities who can and do resist effectively. But early Italian history seems to feature many examples of mad oligarchs. This is one reason the Contraptions Book Club is starting out with a book on the history of Venice (though it was more the island of sanity in a mad Italy).

We’ll learn if Musk is a full-blown mad oligarch soon enough, or whether other forces will rein him in. Twitter arguably went down a ruinous path, but is not an example of Schmittian sovereignty at work, since he was in fact forced to buy it by the rules governing buyout bids — so the story is mostly one of the rules playing out ruinously, rather than exhibiting exceptional excursions driven by Schmittian sovereign actions.

The second archetype is the unaccountable bureaucrat in the middle. A member of a body of individuals who don’t pop individually, but in aggregate embody a great deal of Schmittian sovereignty. The first, top-level Schmittian sovereign archetype these days likes to refer to this competing second class as “Professional Managerial Class” or PMC, a James Burnham term of art deployed as a slur.

The term “Deep State” (which can be traced back to the Turkish/Ottoman/Byzantine prototype) is the usual mental model of the monstrous middle here. Again, we can ask the morbidity question.

It is normal for a professional institutional elite to enjoy a great deal of Schmittian sovereignty within their domains. Every society, historically, has chosen to overlook the excesses and arrogations of authority of talented administrators. The system cannot work unless such individuals are empowered to make use of systemic leeway (J. P. Rangaswamy has a nice little post on Dave Weinberger’s idea of leeway). This is how the “letter of the law” acquires a “spirit” — by allowing certain people exception-making abilities.

Some sort of “Deep State” exists in any reasonably complex society. But what makes a Deep State exhibit morbid symptoms, and therefore turn monstrous, is when the aggregated Schmittian sovereignty starts to exhibit emergent properties that are clearly in a state of exception in relation to the nominal mission. When the spirit of the law turns into an evil spirit so to speak.

We use the word capture (as in “bureaucratic capture”) to refer to specific localized instances of this (for example, a police department being in the pocket of the local mafia don), but you only get a mad Deep State when the various instances of capture coalesce in unholy mutually reinforcing ways to make the entire contraption systematically deviant. An example might be Ancien régime France.

Finally, we can complete our inventory by adding the idea of a mad anarch. Ernst Jünger, though he is much demonized today, was largely a misunderstood prototype of a normal anarch. His story reads like that of an anarch with some exception-making agency, but not a mad one.

True examples of mad anarchs might be perpetrators of mass shootings, lone-wolf assassinations, mail-bombing/mail-anthraxing, and stochastic terrorism with trucks. We obviously have a growing wave of such things that I don’t want to analyze, of increasing variety and illegibility, and it’s useful to club it all together as a different, looser kind of aggregate, de facto Schmittian sovereignty. An oozy sort of aggregate that is distinct from the monolithic aggregate that is the Deep State.

In a way there is no point over-analyzing why Mangione or Trump’s would-be assassin, or the Vegas or New Orleans terrorists did what they did. The manifestos and murky ideological provenances doesn’t matter. The fight among more “normal” ideological actors to claim credit or deny blame is irrelevant — mad anarchs belong with other Schmittian sovereignty archetypes, outside the logics of manifestos and ideologies, and organized action driven by them. A different kind of analysis applies to them.

So we have a set of archetypes of Schmittian sovereignty at the top, middle, and bottom of the societal org chart. I am deliberately not calling it a class hierarchy, since that is not the relevant scaffolding here — exception-making capacity exists in relation to the technical-functional hierarchy of a society; the society-as-a-machine, which may or may not have strong correlations to its social hierarchy.

But mad emperors, mad oligarchs, mad Deep States, and mad anarchs are only one half of the story — monsters corresponding to the morbid symptoms appearing at sovereignty loci where the system’s exceptions are made.

What about the other half of the story, the regime of system behavior accounted for, modeled by, and governed by, the rules themselves. What does it mean for morbid symptoms to appear in the rules themselves? What sorts of monsters appear here?

Morbid Systems of Rules

Rules relate to architected behaviors and protocolized verbs, so it is useful to switch reference frames and talk about the corresponding objects and nouns. At societal scale, this usually means large assemblages and hyperobjects that emerge from the rules that we are continuously refining and developing them while inhabiting them.

Like caterpillars spinning pupae around themselves, we create societal machines around ourselves. Every “world” is in fact co-extensive with some such machine, and this has been especially true since early modernity. I’ll call such world-scale machines hypermachines: machines that you must inhabit even as you attempt to build or change them, and which cannot be governed without significant discretionary exception-handling capacity. And here world scale is not necessarily planetary or global. It is simply a scale past which you have no choice but to inhabit the system even while building or repairing it.

An airplane for example is not a hypermachine. You mostly build or repair it on the ground. You can make small improvised fixes in the air, but in general, you cannot literally fly a plane on a “wing and a prayer.” A house is not a hypermachine. You don’t have to live in it as you build it.

Let’s take a quick, incomplete inventory of how systems of rules/societal hypermachines can turn morbid and monstrous:

There are too many rules

There are too few rules

The rules change too fast

The rules don’t change fast enough

The rules have epistemic/ontological foundations that are too irrational for the circumstances (eg: trying to regulate genetics technologies with creationist principles)

The rules are too ambiguous, inconsistent or incoherent (entropic, in brief)

The rules are obsolete and focused on circumstances that no longer exist

The rules are blind and cannot see new circumstances where they blunder

The rules do not comprehend the state of technology sufficiently well

The architecture is fatally flawed at an un-engineered emergent level

The world is operating too fast for the rules (a Nyquist sampling theorem type problem)

The rules do not have requisite variety in relation to the governed system

These are phenomena to be understood pragmatically. Hypermachines rarely reach the level of design integrity where you have to entertain more esoteric worries like Godelian incompleteness. These morbidities are the morbidities of contraptions.

Note that none of these morbidities requires monstrous Schmittian sovereignty to be present in the system. You can have any or all of these phenomena with no mad emperors, mad oligarchs, mad Deep States, or mad anarchs running around. In fact, what we might call normal madness (madness of rules) and exceptional madness (madness of Schmittian-sovereign actors) fuel and justify each other.

This is in fact the phenomenology of the Gramsci Gap — normal madness and exceptional madness locked in a cage death match with each other. Because we like humanized narratives about exceptional people (and people who make exceptions are ex officio themselves exceptional), it is tempting to see the various mad sovereign actors at different loci as primarily being in competition with each other (for example, mad emperors and mad oligarchs vs. mad Deep States or "PMCs”; health insurance CEOs vs. assassins), but the larger yin-yang dynamic is between normal and exceptional madness. The power-crazed mad bureaucrat is just the immediate enemy of the mad emperor. They merely fight over who gets to make which exceptions. The larger enemy of both is the ordinary bureaucrat following the mad rules conscientiously.

Rules go mad because our intuitions about systems break down at hypermachine scale, and we do exactly the wrong thing. For example, if there are too many rules, you must first make more rules about how to remove rules, which might work in simple cases, but doesn’t in truly complex cases. Systems you must inhabit while modifying behave differently from ones you can step outside of and analyze and reshape from a god-like external perspective. Systems that call for an irreducible minimum level of human exception-making capacity (or: which cannot work without leeway) behave differently from ones that can be fully autonomous (the “Work to Rule” pattern of collective action has become the cliched example of this).

I want to discuss three examples of reasonable-seeming complex system machinic laws that break down at hypermachinic scale, to illustrate this path to madness.

Gall’s Law

First, take Gall’s Law, which I have myself quoted often. It states:

A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked. A complex system designed from scratch never works and cannot be patched up to make it work. You have to start over with a working simple system.

If you look at the data of history, this is obviously true of complex but smaller-than-whole systems that are embedded within a larger system and interact with it via boundary conditions.

The way this works is, while the failing system is limping along with increasingly expensive and ineffective patches, a “working simple system” pops up somewhere outside it, but in the neighborhood, and in the same stable embedding context. This is in fact disruption in Christensen’s sense, which Gall’s Law prefigures. When the juxtaposition of failure and success becomes obvious enough, large-scale defections finally kill the incumbent and enthrone the disruptor on the margins.

In such sub-maximal complex system, the embedding context itself is not failing, therefore an interregnum in time can be replaced by an interregnum in space. Early adopters switch early, late adopters switch late, non-adopters die with the old world, young people are born “native” in the new world. But the death of the old and the birth of the new can proceed in a much more parallel way. It would suck to be locked into the old, unable to exit or defect to the new, but at a societal level, there need not be a gap. My own transition from landlines to feature phones to a Blackberry to smartphones was largely smooth and seamless, with no “Gramsci Gaps” with monsters troubling me (well… except that my brief flirtation with Blackberry was with that monstrous clicking touchscreen). But if you were an employee at RIM or Nokia through these evolutions, things were probably not as easy. Gall’s Law would have applied. You could not have gotten to the iPhone starting with a Blackberry and adding a clicky screen to it.

But Gall’s Law fails at maximal scale! This is most obvious at civilizational scale. Asia didn’t “fail” when Europe leaped ahead a thousand years ago. Europe didn’t get mothballed when America leaped ahead a hundred-odd years ago. Those older complex systems just continued evolving along new, perturbed trajectories despite a lot of agonizing about their impending doom. Almost everybody at this point has moved from feature phones to smartphones. But obviously “almost everybody” has not, and cannot, move to new civilizations as old ones decline. Slash-and-burn only works at primitive agriculture scale with a lot of forest around you.

The problem with Gall’s Law lies in the “complex system that works” part. Just because a system does not work for some parties does not mean it is broken. It can continue along, being evolved by those inside it, for whom it still works.

Brooks’ Principle

A second example of a complex systems law that fails at scale is Brooks’ principle2 of computer systems architecture, usually stated as “Plan to throw one away.” As in, design a system purely to learn how to design that kind of system, and then throw it away and do the real one. A sort of “design study” or “proof of concept prototype” approach that definitely works for simpler machines, except that it is built, tested, and used in production. Think of it as an improvised hack that is eventually replaced with a “real” solution, except that the “hack” is a complex production system in its own right, requiring significant engineering. This principle does not work at hypermachine scale.

I suspect this law never even worked in Frederick Brooks’ time and domain (the 1960s era of minicomputer architecture), but if we generously allow that it perhaps worked at the time, it certainly does not work now. Joel Spolsky tagged this point in his post, Things You Should Never Do. He offers a lot of obvious pragmatic reasons that may or may not apply (such as throwing away all the learnings about weird exceptions and corner cases, market leadership, and so on).

But at hypermachine scale, societal scale, there is a more fundamental reason you cannot throw the system away even if you want to — the system is so large, and so unique at every scale, the very act of building the system has changed the circumstances you’re building for and transformed the resource environment. You are now necessarily building V 2.0 on the carcass of V 1.0 rather than on pristine territory. This is true not just of material conditions, but human conditions too. A sufficiently large system probably employs everybody with any ability to contribute to building it. As humans, they will have been changed by the experience of building V 1.0, and will have very different beliefs, desires, and intentions at the other end.

Mathematically, sufficiently large complex systems induce non-ergodicity/path-dependence into their environment as they emerge because they “corner” all the resources required to build them, and transform those resources. So building one to throw away does not work. There is nowhere to throw it. And normal workarounds like building one to throw away at a smaller scale does not work because the system does not behave the same across scales.

Or to put it another way, hypermachines are always at Version 1.0. It’s just a different 1.0 each time, built on a pile of older 1.0 corpses. You can never step in the same river of hypermachines twice.

Parkinson’s Law

My final example is one of Parkinson’s many laws. This one asserts that “… a perfection of planned layout is achieved only by institutions on the point of collapse.”

Again, this is true of simpler complex systems. For example, the finest piston-engined fighters, like the Vought Corsair, were built right around when early contraptiony jet aircraft were taking over. Piston-engined designs reached near-perfection before the entire tradition collapsed.

But this is clearly not true of more complex systems. The qualitative boundary is again where hypermachines begin. Where you must inhabit as you build or modify, and where a space of exceptions must always be made outside of the system’s own system of rules.

Hypermachines don’t reach a state of perfection and then collapse. Instead, they continue evolving past into increasingly baroque states, entering the Gramsci Gap. Both exception-making and rule-following turn morbid and monstrous.

In fact, there is no sense in which they even pass through a state of “peak” perfection. Why is this?

Utopian conceptions of worlds can usually be reduced to societal hypermachine architectures that are so complete and faultless, they do not need to be suffused by a ghostly phlogiston-like Schmittian sovereignty soul. They have no need for open-loop exception making driven by human discretion; no need for Schmittian sovereign agency either concentrated in a monarch or distributed. Hypermachines that don’t have real leeway because they don’t require it. Such hypermachines are — to my mind — obviously impossible. Not even pumping AI into everything will create such hypermachines. Exception-making will always be necessary, and will itself never be invulnerable to its own morbidities.

But a thing that can happen is that a lot of the exception-making and exercise of Schmittian sovereignty retreats from view, so that there emerges a world behind the world, an esoteric world behind the exoteric one, peopled by an invisible Straussian elite. When this happens, the visible world can seem to approach and pass through a state of perfection, leading to mythologization (the late Victorian Age/Edwardian Age is one example; 1950s America is another). But arguably this appearance of perfection is meaningless and superficial; about as believable as the worlds of P. G. Wodehouse or Conan Doyle or Norman Rockwell paintings. It is a theatrical perfection.

Taken together, these examples of intuitions about complex system failing at hypermachine scale suggest how and why morbidity enters systems of rules: We detect early signs of morbidity and do exactly the wrong things, amplifying the morbidity, or trading one morbidity for another, rather than addressing it.

I’ll stop here for now, but now that we understand the Gramsci Gap and the monsters that lurk within them, the obvious next question is — how do new worlds exorcise the monsters and emerge? And how can we be part of that emergence instead of descending into monstrous morbidity of one sort or the other?

The word for a device that takes feedback from the output of a system and uses it to control it with reference to something that’s not part of the system is “regulator” and the first modern mechanical regulator, for James Watt’s steam engine, was called a “governor” (the clock escapement is an older example, but in my opinion has features that make it not quite a true regulator).

From The Mythical Man-Month. The more famous Brooks’ Law is “adding programmers to a delayed software project delays it further” which is also not true today.

The Gramsci Gap reminds me of Empire of the Sun, a 1987 movie where a young Christian Bale is in a Japanese POW camp during WWII. His American mentor (John Malkovich) scolds him at his excitement that things are going poorly for the Japanese and the war appears to be ending. He says (according to IMDB): "It's at the beginning and end of war that we have to watch out. In between, it's like a country club." Even in such wretched circumstances as being a prisoner of war, if the mechanisms and rules and paradigms are stable and understood, a shrewd operator can find positions of advantage. Indeed Malkovich's character Basie seems to fit the anarch quite well, remaining inscrutable to his cohort (for he has no friends), and always managing to slip the rules despite being given no formal exemptions.

I was a child in a military family and we moved every 2 years, so I really felt Basie's admonition in my bones. I faced repeated liminal periods, where it seemed as soon as I figured out the folk mores and social order of my immediate surroundings I was transplanted to start the process over again. I remain obsessed with and keenly aware of all things liminal to this day, and wholeheartedly agree that "western" society is facing such a period now.

are you sure about "Asia didn’t “fail” when Europe leaped ahead a thousand years ago."? i might characterize colonialism in south America, Africa and Asia (culminating in the British empire) as such failure.

OTOH, is Singapore an example of a complex machine built from scratch and still working (having gone through changes on the fly)?