The New Systems of Survival

Jane Jacobs reconsidered in the Permaweird

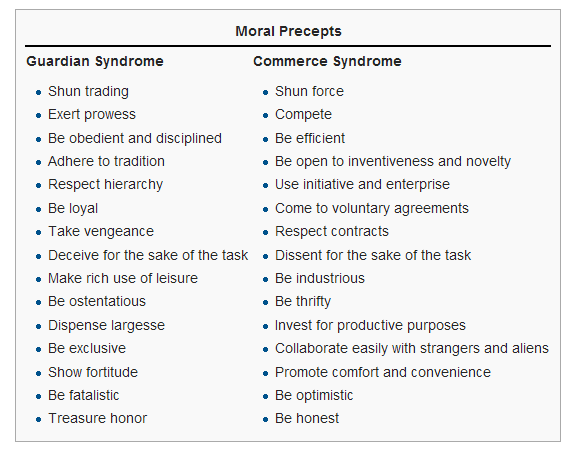

About a decade ago, I was briefly obsessed with Jane Jacobs’ Systems of Survival model from her 1992 book of that name. In brief, she argued that the world is made up of two types of people, who operate by two competing and incompatible value systems that she labeled guardian syndrome and commerce syndrome. Here is a table from the Wikipedia page summarizing the key differences:

As is usually the case with me, I never actually read the book,1 but just went off down my own bunny trail based on a Wikipedia-level gloss. In Saints and Traders: The John Henry Fable Reconsidered (June 2014) I considered the model in the light of the fable of John Henry, and labeled the archetypes corresponding to the two syndromes saints and traders. In The Economics of Pricelessness (August 2014) I made up a model of how economic relationships play out both within and between the two tribes.

In 2014, I thought the model was great!

In 2014, most people were clearly either Saint types or Trader types, though in a nuanced yin-yang way, as in Saints have a Jungian shadow of Trader going, and vice versa. So you get certain predictable patterns like successful business people being driven by honor, loyalty and vengeance, or traditionalists with a basic aversion to commerce being industrious, inventive, and culturally open.

Despite these Jungian complications, as a broad strokes model, tastefully interpreted, the Jacobs model basically worked in 2014. The eigenvalues of the model, so to speak, which tended to govern the subsidiary values, were the attitudes most directly related to money and transactions.

To test people for their dominant syndrome, you could just probe how they felt about money. Saints in 2014 were fundamentally people who prioritized personal relationships over transactional ones, often being willing to make financially irrational decisions to serve priceless personal values. Traders in 2014 were fundamentally economic rationalists who would often be willing to sacrifice personal relationships in service of financially rational decisions.

Take a look at the table and ask yourself: Does this describe the world of today as well as it did the world of 2014? If it helps, pick a couple of specific people as examples, and try to profile them using the two columns.

I don’t think the model works anymore. There are many people I used to consider clear Trader types in 2014 who now act more Guardian-like than the Pope. And (to a much lower extent), there are people I considered pure Guardians in 2014, who now strike me as embodying the spirit of Commerce (though not necessarily in a commercial domain; I mean simply being willing to bring a spirit of win-win expectations, compromise, openness, mutual understanding and negotiation to relationships with outgroups).

The eigenvalues of attitudes towards money and transactions are no longer reliable indicators of anything. For example, crypto people are possibly the strongest believers in markets, contracts, and economic rationality. And they all strike me as more religious than evangelical Christians.

And the break in the model is not subtle. It’s not merely fraying on the edges. It feels like it’s not even wrong anymore. A deep fault line has emerged that has completely undermined it.

Given that the Jacobs was a product of 60s/70s conflicts between Johnsonian Great Society and Reaganesque schools of governance, and published her book in 1992 (probably Peak Neoliberalism, given that Bill Clinton rose to power by simply adopting the Reagan playbook), I suspect her model is, unconsciously, a very particular one, reflecting the peculiar historical era it was developed in.

We’re not in that world anymore, so it’s not surprising that the model doesn’t work.

Which brings me to the idea I’ve been noodling on for the last few months: A new pair of systems of survival has emerged that are defined by opposed relationships to the problem of the growing ungovernability of the increasingly complicated world, and the collapse of previous theaters of pretending to govern or be governed (see my newsletters from the last two weeks, The Art of Pretending to Govern and Bullshitization and Common Indifference Problems).

To develop this model, we need to start with a test that divides the world into two basic pieces governed by a metaphysical duality.

The LinkedIn-Twitter Test

You can get to the core of this new pair of systems of survival using what I call the LinkedIn-Twitter test. Given any system, person, behavior, or idea, does it strike you as a LinkedIn type thing, or a Twitter type thing? Here, I mean LinkedIn and Twitter as motifs for larger socioeconomic tendencies and cultural moods that the two platforms exemplify and embody particularly well, but aren’t limited to them. The test is metonymically named.

There is something of an American bias to the test of course, since both platforms are strongest and most influential in the US, but arguably, the test is global and there is no better pair of motifs for what I’m getting at.

I ran a poll a few weeks ago, asking people which of the two platforms they’d want to eliminate from existence (not just quit personally). And as I fully expected, but most people apparently didn’t, the results were about even, with, as I expected, a slight edge for people wanting to erase LinkedIn from existence.

What was interesting was the polarized reaction of surprise some people had to the result of the poll as it became clear: Twitter-erasers being shocked that anyone would consider erasing LinkedIn, and vice-versa. Most also seem surprised the platform they want to erase exists at all. They can’t fathom why anyone would go there, and why it hasn’t died already.

As my screenshot above shows, I personally voted to get rid of Twitter. But I do understand why others might have chosen LinkedIn, and why some people can’t comprehend choices that differ from theirs.

The reasoning was also fairly consistent. People who voted to keep LinkedIn saw the real deep value in professional networks for career development, recruiting and so on, and saw Twitter as mostly a toxic cesspool of ignorable noise. People who voted to keep Twitter saw real deep value in the “alpha” — real actionable intelligence signals bubbling out of the noise — and saw LinkedIn as a toxic theater of bullshit pretensions and credentialed puffery by useless and clueless people.

The LinkedIn-Twitter test applies to more than the narrow preference between the platforms. Almost anything can be put to the test. To apply the test, think of it as testing for resonance/harmony vs. dissonance, when you juxtapose the thing with our two test entities.

Substack is clearly more LinkedIn than Twitter, while WordPress blogs are more Twitter than LinkedIn.

Instagram is more LinkedIn, TikTok is more Twitter.

YouTube I think is mostly Twitter culture, though it features a lot of LinkedIn content.

Trump and the GOP are Twitter, Kamala Harris and the Democrats are LinkedIn.

Globally, ethnonationalist parties are typically Twitter, while progressive parties are more LinkedIn.

BUT… at an individual level, far right and far left are both Twitter (including the far lefties who would want to erase Twitter), while centrists both right and left are LinkedIn.

Among the Twitter alternatives, the Fediverse and Threads are more LinkedIn, while Bluesky and Farcaster are more Twitter.

America is more Twitter, the EU is more LinkedIn…even the ethnonationalists.

Antivaxxers are Twitter, vaccine people are LinkedIn.

People who flaunt their degrees are LinkedIn, people who “do their own research” are Twitter.

Bureaucratic organizations, whether traditionally left-leaning (welfare orgs) or right-leaning (military/police orgs) are typically LinkedIn.

Cultural scenes, whether traditionally left-leaning (artists, musicians) or right-leaning (motorcycle clubs, MMA) are typically Twitter.

Appeal to institutional authority is LinkedIn, appeal to charismatic authority is Twitter.

Curiously, which one you vote to eliminate does not indicate what kind of person you are. There are Twitter people (far left types) who probably voted to erase Twitter, even though they’re really not LinkedIn types. What they really want is for Twitter to be left-leaning. And there are LinkedIn people (struggling with career opportunities/job leads for eg.) who probably voted to erase LinkedIn even though they’re not really Twitter types. What they really want is to be on LinkedIn getting job offers and having important and famous people looking at their profiles. They’re just mad LinkedIn doesn’t work for them.

Equally curiously, how you succeed or fail is not an indicator either. I’ve probably been a vastly more successful “Twitter person” even on LinkedIn-style media, but I’m fundamentally a LinkedIn type person.

The test applies to almost everything, not everything, so I won’t try to do silly things like trying to classify apples and oranges as LinkedIn/Twitter fruits. What’s in scope for the test is anything with a sociopolitical salience. So while I don’t think apples and oranges can be classified by the test, seed oils are clearly LinkedIn and anti-seed-oil theories are clearly Twitter.

Weirdness and Hypernormalcy Syndromes

What does the LinkedIn-Twitter test measure?

Why do some things feel intuitively like they belong with one or the other? What, if anything, is on the edge between them?

I think the test measures how you instinctively react to the challenge of surviving in an increasingly and visibly ungoverned world settling into a Permaweird state. The two possible responses are:

Lean into the weirdness, as in when the going gets weird, the weird turn pro

Lean into what Adam Curtis called hypernormalcy in his documentary HyperNormalisation

The latter requires a word of explanation. The documentary (a typical Curtis documentary — spazzy and wild-eyed, but entertaining and insightful in parts) uses the term to refer to an increasingly bizarre, surreal, and distorted kind of institutional normalcy that has become increasingly unmoored from anything real, which people nevertheless double down on and cling to harder and harder. Ie, the weirder the world gets, the harder they cling to normalcy. The surprising thing isn’t that they do it. It’s natural to cling to what used to work for reassurance. The surprising thing is that it works as a system of survival.

This is obviously LinkedIn world. It is a world-scale larp of normalcy circa 2014 or so. A world it takes very talented contortionists to continue to perform as though the last decade hasn’t happened at all.

Let’s call leaning into weirdness the Weirdness Syndrome, and leaning into hypernormalcy the Hypernormalcy Syndrome. These are the “new systems of survival” in my headline. You can self-classify by looking at whether you feel more at home on Twitter or LinkedIn, even if you don’t like the experience of feeling at home there. A traumatizing home is still a home.

Let’s call the associated archetypes professional weirdos (or just weirdos for short), and hypernormies, or just normies for short.

Weirdos living by a Weirdness syndrome code of values, and normies living by a Hypernormalcy syndrome code of values. Creative naming, I know.

Is either of these strategies obviously more rational and adaptive? A lot of people seem convinced that one of the strategies is obviously correct, and that you’d have to be clinically insane to adopt the opposed strategy.

Unfortunately, by that measure, you’d have to classify roughly half the world as insane. I don’t know about you, but to me that suggests that the word insane is reduced to utter vacuity. Much more likely you’re both missing something about both strategies. You are blind to critical affordances of the opposed syndrome, and to critical limitations of your preferred syndrome.

Let’s ask a better question: In what ways are the two syndromes adaptive vs. maladaptive?

The Weirdness Syndrome is obviously more adaptive in one way — being attuned to the growing signals of weirdness on the margins of normalcy, and reacting faster to it. LinkedIn people (hypernormalcy syndrome people), outside of their narrow institutional specializations, are simply less aware of what’s going on in the world and usually don’t even know it.

But unfortunately for weirdos, simply attending to weirdness more closely does not make your mental models of what is going on any better, or your faster reactions actually superior. You might notice weirdness first, but adopt a maladaptive crackpot response. Or you might adopt exactly the wrong strategy while the oblivious person who does not notice it at all might default unseeing into the right strategy. Data without generalization, as Robert Pirsig noted, is just gossip.

The Hypernormalcy Syndrome is obviously more adaptive in one way — rationally holding on to the very high residual value in the unraveling institutional landscape, and being able to navigate and access opportunity spaces within it, using well-established economic extraction patterns like “careers” and “jobs.” Even if the landscape itself is a bizarrely distorted fake world that’s become completely unmoored from reality (I don’t think this is true btw), there is real money to be made in it. Money made from participating in surreal theaters is still real money. A nice house bought with that money is still nicer than a slummy one you might inhabit while being Very Online and attuned to weirdness.

Each side overestimates the power and threat of the other. Weird syndrome people think of Hypernormal syndrome people as a nefarious cabal of Deep Staters hatching a conspiracy to destroy everything of value. Hypernormal syndrome people think Weird syndrome people are dangerous lunatics determined to blow everything up driven by extremist agendas.

This is something of a short-medium term view. I personally rely on both Twitter and LinkedIn worlds to some degree (though not on either of the actual platforms) to survive. Some doors open for me because I have a PhD and brand-name credentials and resume items. Other doors open for me because I have a successful track record as a blogger and shitposter. It’s hard for me to say which is more important for my own survival. But on balance, I’d have to go with LinkedIn (as in, the motif for hypernormalcy, not the site itself). My system of survival is to make a home in hypernormal spaces, but with frequent travel to weird spaces.

Relationship to the Old Systems

If I do my accounts roughly by the old systems of survival, I’d have to say my current net worth (Commerce syndrome valuation) is 50-50 attributable to the Weirdness and Hypernormalcy syndromes. My honor and reputational capital (Guardian syndrome valuation) is also 50-50 split across the two new syndromes.

Can we say that either of the new syndromes is a clear descendant of one of the older ones? It’s hard.

I am tempted to say the Hypernormalcy syndrome is descended from the Commerce syndrome, because nobody successful in a conventional careerist way is actually cluelessly bought into the theater of hypernormalcy. To participate successfully in LinkedIn-land you have to have a certain clear-eyed Zizekian cynicism, speak in corporate-speak bullshit without being mind-captured by it, and so on. Truly clueless hypernormies wouldn’t last long, or get jobs on LinkedIn. Or even successfully earn credentials like valuable degrees. You need a certain ironic distance from institutional realities to be able to navigate them with any success. You need a certain tolerance for what the reflexively weird might view as bullshit jobs and activities, and an understanding of their actual non-obvious utility.

But it’s easy to overstate the strength and consciousness of that ironic distance. I do meet a lot of successful “LinkedIn” types who are at best very dimly aware of the sheer bizarreness of their theatrical world. It becomes too real for them the way wearing VR glasses for too long might get too real for a gamer. It’s a kind of mask trance.

Equally, even though we say things like “Twitter is tribalized” (I myself have argued for a detailed honor-society understanding of the extended Twitter-verse as the Internet of Beefs), suggesting that the Weirdness syndrome is the “new” Guardian syndrome, that’s not clear either. There are a lot of very clear-eyed engagement farmers and systematic hustlers with very Commerce syndrome sensibilities.

So while there are no clear lines of descent from old systems of survival to new, clearly, the new systems are refactoring the old ones in powerful ways.

In fact, I think there are distinct world-processes underway today (by world-process I mean things like industrialization, globalization, urbanization…), that correspond to the simultaneous growth of both weirdness and hypernormalcy. The world that was once divided along guardian/commerce lines is now getting unbundled and rebundled along weird/hypernormal lines.

I call these processes LinkedInification and Twitterification.

A thing gets LinkedInified when it starts to get governed by systematic “career hacking” type behaviors that can be taught, learned, and practiced with a certain dispassionate indifference to human costs, and a clear separation between “work” and “personal” personas. LinkedInification is hypernormalization, but without the suggestion of conspiratorial orchestration that the documentary tries to convey.

You don’t have to wear “business professional” clothes and put up “professional headshot” pfps to be a LinkedIn type. You can do that by hewing to the optics of any legible script or pattern, and working by reliable playbooks of any sort. For example, statue-head pfps and a feed full of “beautiful” architecture posts is, in a weird way, a LinkedIn style hypernormal career strategy. Or the very characteristic affect and comportment of YouTube stars.

A thing gets Twitterified when it starts to get governed by raw, instant, id-driven responses to unfiltered reality signals, with streaks of real emotion and authenticity breaking through in what is meant to be pure calculated performance, whether or not that authenticity is actually pleasant to behold. Twitterfied behaviors tend to unpredictably trigger explosive viral responses, and the main sign of it is the emergence of dopamine loops that people can get hooked to.

Here is the real tell: LinkedInification moves societal dynamics towards what Taleb called Mediocristan, while Twitterification moves societal dynamics towards what he called Extremistan.

Ironically, Twitter itself is getting weirdly LinkedInified, and LinkedIn is getting hypernormally Twitterified. The archetypal social spaces of the Weirdness and Hypernormalcy syndromes are starting to leak into each other.

If you haven’t been on LinkedIn in a while, a strange sort of addictive quality has been slowly emerging on the site for a few years. As the hypernormalcy theater gets more surreal, it gets more entertaining and addicting to watch. It is now even possible to “go viral on LinkedIn,” an Extremistan dynamic that was previously absent on the platform. The faceless corporate drones are even evolving their own Type of Guy/Gal subspecies.

And equally, if you haven’t been on Twitter lately, since the Muskening, it is weird how the addiction loops have weakened due to the growing amount of quasi-professionalized soulless engagement farming going on. There are people using Twitter to grow careers the way LinkedIn people did a decade ago. There is a surreal vibe of non-viral mediocrity to the recognizable engagement farming patterns and their rewards. Threads that get very popular sometimes strike me as “Vice President of Seed Oil Twitter Issues Press Release.”

This confusion will only increase, as hypernormal and weird currents in the zeitgeist begin go mix and churn together. Instead of being widely separated regimes of society, Taleb’s Mediocristan and Extremistan will exist as interwoven textures. You will find it harder and harder to stay in just one of the regimes.

An Epistemic Stalemate

If you’re convinced one side of the weird/hypernormal divide is obviously correct, and can’t see why the other side manages to exist at all, let alone attracting half the population, you might have developed a certain blindness to a prevailing condition I call epistemic stalemate, which manifests as neither side being a good default place to source your answers to the questions and survival challenges life throws at you. Even on a single question or concern, you might have to assemble your picture of reality from pieces sourced from both sides.

For instance, take the current condition of Boeing. Obviously, a LinkedInified mess of financialization, non-technical leadership, monopoly apathy, and so forth. Boeing is mostly a clear-cut case of Hypernormies Gone Wild. Planes are crashing (the 737 MAX mess), doors are flying off planes, and a spacecraft is stuck in space. Weirdos watch aghast as the hypernormies put on a theater of catastrophically bad showrunning in an important theater of civilization.

There are two resolutions to the “Boeing problem” on the table:

The Weird answer: Let Elon Musk start an airliner company or invest with his Magic Touch in a few aerospace startups and force airlines to buy their planes

The Hypernormal answer: Let traditional aerospace engineers from Boeing, Lockheed, maybe even Airbus, take a stab at fixing Boeing from the inside

Neither answer is obviously right or wrong. There is some merit to the idea that some brisk competitive energy and disruptive reinvention of airliners would level up air travel. It is very likely that some weird high-school dropout autodidact types in garages might think up revolutionary new ideas for air travel that actually work. That’s how the industry started (look up Jack Parsons) and how it is continuing (besides Elon, look up Palmer Luckey’s Andruil). Many of these weird types might even be “deplorables” in Dem-speak. And maybe the number of airliner crashes have to go up before they can go down, a la SpaceX’s exploding rockets early on.

But aerospace isn’t a sector you can revolutionize overnight by releasing an app. It’s unlikely your business trip next week will be on anything other than a Boeing plane if you’re in the US.

There is also merit to the idea that the answer lies within the bizarro-surreal theater of hypernormalcy. While the epistemology of the hypernormal world might not be systematically reliable, there is no question that Boeing as an organization, despite its problems, is likely the repository of vast amounts of relevant knowledge and expertise. If Boeing and Airbus both suddenly vanished next week, with all their knowledge, most of us won’t be flying for decades. It would take even the finest weird geniuses decades longer at the very minimum to rediscover the lost knowledge required to build large airliners. Only smaller regional jets and corporate jets would be flying around.

This is what I mean by epistemic stalemate. Both sides have enough merit to their claims to the truth to be not just credible, but necessary to solving most problems.

To understand the challenges of the stalemate, you only have to look at Tesla — an icon of Weird industry, led by possibly the leading Titan of Weirdness. But it is telling that the main Tesla factory in Fremont was originally a GM-Toyota plant. Large portions of its workforce are auto industry veterans. And despite the radical innovations the company has brought to automotive manufacturing, it also uses a vast amount of the knowledge and industry infrastructure of the traditional auto industry. If the traditional auto industry vanished by magic, despite all its aspirations of being a raw-materials —> cars full-stack company, Tesla would be in deep shit. It is one thing to claim you’re operating from “first principles,” but quite another to actually start with a literal blank canvas.

This stalemate is deeply frustrating to both sides, because neither likes relying on the other side for essential functions.

So they descend to name-calling.

Weird vs. Normie as Insults

For a decade or longer, the phrase “mainstream media” has been used as a slur for its role in defining the boundaries of normalcy. Words like “expert,” “elite,” and of course, “normie” have also turned into slurs.

All these slurs point to the hypernormal world. To LinkedIn.

While some are more preferred by the right, it is noteworthy that none of these insults is particularly strongly right/left coded.

The most relevant one for our purposes in particular, normie, is strictly neutral. I’ve heard people of all self-characterized marginal political persuasions use it as a slur against “centrists.”

In the last few weeks, the hypernormal world has finally adopted what in hindsight is the natural counter-move — weird deployed as a slur by Democrats in the US against the Trump campaign. But it’s revealing that it is a center-to-margins insult, a dual of normie, rather than a left to right insult. In fact, it would probably work just as well aimed at the far left.

Since I’ve spent a decade shilling my Great Weirding neologism and theory (I coined the term, rather appropriately, in a very hypernormal place: an Atlantic essay), this development has left me feeling…a bit bemused. I’ve even been writing a whole series titled The Great Weirding, and it’s one of the main frames I shill in my hypernormal work gigs. So weird as a slur just feels… weird to me.

But weird as a slur has apparently been… weirdly effective?

This surprises me. I’ve personally always used the term in value-neutral ways as a description of the zeitgeist, and in a mildly positive way as a character descriptor. I don’t think of myself as weird, but in general, I admire many people I see as weird. I’d even go so far as to say that weirdness is the main trait I tend to admire in people, over other traits like intelligence, courage, ambition, imagination, or talent.

But while I don’t admire either Trump or Vance, and it wouldn’t have occurred to me to describe either as weird, clearly it is appropriate in some way. As in, they’re the opposite of the hypernormal type of party-machine candidates for office from either party, like the Obamas, Bidens, Clintons, Bushes, or Romneys. The sort of weirdness I admire is, I suppose, a subset of all possible varieties of weirdness.

Still, there is something really strange and old-fashioned about using weird or weirdo as a slur in 2024 at all.

The thing is, yes the people being called weird are weird, but that’s not what’s objectionable or distasteful about them as political candidates or human beings. I dislike Trump and Vance not because either is weird, but because they hold ugly attitudes also held by many non-weird people, and exhibit ugly behaviors I won’t condone that are also exhibited by many normies.

And the candidates I do support, I do so not because I think “not weird” or “hypernormal” is an admirable trait. That too is value-neutral to me. The weird/hypernormal axis for me is orthogonal to the moral axis. If anything, to the extent Harris/Walz are more (hyper)normal, that’s neither a strike against them in my book, or a point in their favor, though overall I like them both.

So what sort of person finds weird to make sense as a slur, either to dish out, or receive?

If reports of the effectiveness are correct — ie that the insult lands on the intended target rather than merely feeling satisfying and feeding self-congratulation for the insulter — I think it speaks to both the unexpected strength of the hypernormalcy field globally, as well as the insecurities relative to the hypernormal establishment felt by those labeled weird.

Ie, enough people are invested deeply enough in hypernormalcy that they feel strengthened by rejecting weirdness and identifying with the insulting side. And enough people leaning into weirdness on the receiving side have a residual yearning for the trappings of (hyper)normalcy to feel the sting of the insult.

I am not convinced the reports of effectiveness are true, but if they are, I’d guess it’s a version of impostor syndrome at work.

This is clear with both Trump and Vance, who have both spent a good deal of energy in their lives trying to shake off perceptions of being from weird outsider margins, and inserting themselves into spaces that feel more legitimate (in the case of the latter — a “hillbilly” going to Yale to become a lawyer, and rejecting his roots by marrying an immigrant Indian, is about as LinkedIn-careerist as it gets in America). They don’t want to be weird. They want to define and own the new standard of normal. I mean… wanting to be President or Vice-President is possibly the most LinkedIn type aspiration you can have. It’s not only a kind of aspiration I’ve never had, it’s one I can’t imagine having.

I think I missed the sting in weird as an insult in part because to the extent I have comparable anxieties, they point the other way. I’m boringly pedigreed globalist hypernormlacy personified. I both look good on LinkedIn, and have zero impostor syndrome anxieties about how I come across there. My LinkedIn is WYSIWYG. A study in credentialed, unambitious mediocrity. It is neither notable nor embarrassing. It just belongs.

It’s the street cred of weirdness that I lack, and occasionally feel a twinge of anxiety about. I look good on Twitter (or at least used to) and in the blogosphere, but have a certain amount of impostor syndrome relative to people who have a genuine gonzo freak flag that they can fly online to celebrate their weirdness.

The Way of Wojak

So here we all are now, in 2024, caught between hypernormalcy and weirdness, trying to define ourselves against the two competing value sets, in a charged political environment where the two syndromes form the poles of a center-periphery axis of hostile engagement.

This is an interesting place to be. I don’t think it is possible to survive entirely using just one of the two new systems of survival. You have to integrate them. You need synthesis.

Never go full weird.

Never go full hypernormal.

Trust on Twitter, but verify on LinkedIn. And trust on LinkedIn, but verify on Twitter.

I like Wojak, the ubiquitous many-avatared meme character, as a symbol of the right synthesis of weirdness and hypernormalcy.

The character started as the punching bag of more charismatic meme characters, but has outlasted them all. Wojak is the Last Man. Wojak is not just at the bottomwit and topwit margins, he’s the midwit too. He can be be both calm and fretful. He can hang back on the margins feeling weird and superior, thinking “they don’t know…” and thrash about in desperate hypernormal anxieties.

It is interesting how Wojak has survived the various Chads and Pepes and become the new everyman. Everyperson in fact, since the Wojak template has been adapted to feminine and gender-ambiguous presentations too.

In Wojak, the two new systems of survival meet and harmonize. He is both weird and hypernormal. And in the old systems of survival, he simply does not compute at all. Trying to classify him as either saint or trader makes no sense. Guardian and commerce syndromes do not apply.

In the old system, in the mature state in which Jane Jacobs documented it, guardian and commerce syndromes formed a yin-yang duality, each containing a seed of the other, and constantly transforming into each other. This is what gave us the old politics of left vs. right (roughly speaking, guardian vs. commerce).

In the new system, we don’t yet have the mature yin-yang state. The Way of Wojak remains aspirational. People are trying hard to be just one or the other, weird or hypernormal, rather than aiming for a Wojakian synthesis.

But at least we are seeing the emergence of a center-periphery spectrum challenging the dominance of the left/right spectrum. This spectrum runs from hypernormal to weird. And every position along it is a Wojak position.

Wojak is large. Wojak contains multitudes. May we all be Wojak one day.

By the theories in this essay, actually reading books is a very weird thing to do. The hypernormal thing to do is to read Wikipedia summaries, reviews, or most hypernormal of all, paid book summaries. In future, the hypernormal way will be an AI summary.

Another interesting thing going on here, is immigrant effects.

I think Twitter-world is fully aware that the best weirdos are ex-hypernormies. They've done "legitimate" work and have a perspective to share about it. This is why the tech world does so well on Twitter!

There seems also to be a pendulum swinging. If 2018-2023 was about quitting your LinkedIn fake life to pursue your true Twitter weird... 2024 is about Twitter weirdos realizing that being poor but happy is worse than being rich and happy, so embarking on adventure into LinkedIn world in pursuit of riches, but now with a new perspective on the whole thing, and a greater appreciation for the importance of LinkedIn.

Some people become deeply cynical, and think it's a betrayal to be a border-crosser (this is "selling out"), but in reality there are serious gains from trade to be had. It isn't selling out as much as it is creating a real surplus. Or maybe these are the same thing.

Regardless, I think the most important movement in my social circles right now is figuring out which Twitter people are trying to embrace their LinkedIn, and networking them in on the other side, like any good LinkedIn normie would do.

The surplus value created by frequent travel also implies the creation and eventual commercialization of popular "on ramps", "highways", and "travel agencies" between LinkedIn and Twitter. Specifically, I think you need an on ramp into Twitter (you aren't really allowed to just parachute into being weird)... that's inauthentic. But you need a travel agency to approve your visa and fly you into LinkedIn, because you can't just organically grow your career... That's not prestigious enough.

Good point. I was 33 when I started my blog in 2007, and had 15 years of adult life dark matter under my belt that online world can’t see at all. I’m definitely an immigrant like all Gen Xers.