In Search of Liveness

The common denominator of all our concerns

Some years, it takes me quite a bit of random wandering and many false starts before I figure out the themes I’m unconsciously orbiting. This year has been particularly bad, but nearly halfway through, I think I have my three lighthouse themes for the year. No wonder my wanderings this year have felt like a chaotic three-body problem orbit. Nobody should try to orbit three themes at once if they can help it. Especially not unconsciously. It’s very nauseating.

The first theme is liveness. The second theme is bug-fixing, which feels in some ways like a natural dual to liveness (since, at a trivial level of connection, fixing bugs restores liveness to complex systems). The third theme is haunting, which can be understood as a disembodied liveness. I mean haunting not in an occult sense, but in the analytical sense of hauntology. It seems obvious in hindsight, but to make sense of the hot theme of embodiment, it makes sense to look at disembodiment. I have Sam Chua and the participants of the workshop I just helped facilitate in Bangkok to thank for drawing my attention to haunting as a useful lens.

I sense there are deeper links among the three themes, which might involve debugging Heideggerian ideas and exorcising Heideggerian ghosts to get at.1 I’ll save bugs and haunting for future essays. This essay is about liveness.

The idea of liveness is not just an emergent focal theme of my own current interests. It feels like the focus of all currently widespread and urgent-seeming concerns shared by many.

Our anxieties around emerging computing technologies revolves around their alien modes of liveness, which can seem to feed on our own modes. Our cultural anxieties and fears revolve around declining liveness in traditions and grand narratives we are attached to. The so-called meaning crisis is a search for individual and intersubjective liveness undertaken between the Scylla of coercive life-scripts and the Charybdis of enervated post-industrial scriptlessness. The unraveling of institutional and state capacities around the world is an ongoing hemmorhaging of ancient pools and lakes of liveness. Anxieties related to the climate revolve around the displacement of familiar and “natural” modes of planetary liveness by unfamiliar, “unnatural,” and possibly unsustainable Mecha-Gaiazilla forms. An overarching concern with liveness — with worlds dying and being born — defines the Gramsci Gap.

I see the word itself pop up with increasing frequency in other people’s writing, though I’ve been wary of using it myself until now because it is a fraught word. I’ve been particularly leery of using it in the organic, vitalist way it is often used, and have been casting about for a satisfying machinic, non-humanist understanding of liveness, of the sort embodied in an elemental form by a mechanical clock. I now have one, which I’ll share in a bit. We will be exploring liveness in a universalist, contraptiony way. No vibes allowed, especially culture-specific ones (we’ll use a term I made up in 2017, sentiment superstate, if we need to talk about vibes, and go deeper with hauntological tools). In this essay, which kicks off a new series, I’ll be delving into the the vibe sentiment superstate of the Gramsci Gap.

The concept of liveness helps us articulate why we seem to want and pursue the things we do these days. Increasingly our angst revolves not around what or how questions, but why questions, concerning primal desires and motivations. And these why questions always seem to reduce to a search for viable forms of liveness at every scale from chips to civilizations. All angst seems reducible to liveness insecurity. There is something very foundational about this. The desire to be alive precedes any other kind of desire, even if it must sometimes be bootstrapped somewhat arbitrarily starting with higher-level desires. And this search for liveness really is characteristic of the period that started around 2015. The 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, and early 2010s did not feel like a planet-wide search for liveness at all scales. At least not the parts and scales I was immersed in. It did not feel like everything and everybody was constantly trying to either recover a fading liveness, or conjure up new and fragile kinds of liveness. Liveness before 2015 was like water, something you could take for granted and forget about.

What is liveness, how do we know if it is present, and how can we tell when it is emerging, cohering, or draining away?

A machinic perspective on our world at all scales, from literal clock-like simple machines and infrastructures to civilizations and planet-scale liveness, is I think the most illuminating one to adopt.

Talk centered on machines in 2025 will inevitably be shaped by concerns relating to intelligent machines, so I want to assert upfront that liveness is not intelligence. At best, there is an dependency relationship between the two qualities, which I’ll try to unpack.

So even though the question of whether a machine of any sort is intelligent might seem more urgent and pressing, I’m more interested in whether a machine (physical or conceptual) is alive. In many critical ways, a mechanical clock sheds more light on that matter than an LLM. A bacterium — viewed as a machine rather than as an entity designated by vitalist fiat as living — sheds more light than a human genius racing an LLM to the death.

In our always-on protocolizing world, it is also tempting to conflate liveness with the “uptime” of particular life-sign signals, ranging from heartbeats and transactional blockchain clocks to trade flows and streaming broadcasts, to narratives small and grand. Such signals can serve as useful observables, especially for infrastructural forms of liveness that have a tendency to retreat from view, but should not be conflated with liveness itself. They are fingers pointing at moons.

To peek ahead a bit, liveness is a process condition that emerges through, and as, an evolving entanglement of memory and time. The bumper-sticker version of my account of liveness is: a process condition in which time tells memory how to grow, and memory tells time which way to point.

The Contraptions Book club May pick is The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe by Elizabeth S. Eisenstein. Discussion starts May 25.

Liveness as Process Condition

Liveness, tautologically, is the state of being alive. All life, both natural and artificial (in the sense of Conway’s Game of Life for instance), possesses liveness, but contra vitalism, not everything that possesses liveness is life. For a while, I was hopeful that Bergson’s idea of elan vital might shed light on liveness, but now I am inclined to regard it as just naive vitalism with extra steps.

If we are aiming for non-tautological characterization, I suspect it is best to start by thinking of liveness as a possible condition of certain processes, not a property of a particular class of entities or systems we arbitrarily designate as living. We can then ask what characterizes that condition.

Being attached to an entity-centric view of liveness seems to lead to seductive and charismatic but fundamentally flawed notions like Samo Burja’s notion of “live players” — a concept I was briefly seduced by, but am now convinced is dangerously, perhaps fatally misleading. Live-player theory is just uncritical idolatry with extra steps.

Understood as a process condition, liveness may jump across material entity and identity boundaries in unsettling ways. When we speak of Moore’s Law jumping from Intel to TSMC circa 2013 for example, that’s a particular uniquely identifiable instance of liveness leaping across continents, cultures, and histories in a way that disrupts associated memories and temporalities on both sides of the leap. Reading the history of TSMC can and should alter your likely US-centric understanding of even the early history of Moore’s Law. Morris Chang has suddenly been revealed by recent events to have been there all along, right from the beginning, haunting the story. Understanding this results in a historical revisionism operation that rewrites our collective technological memory in powerful and necessary ways, resulting in Morris Chang and Taiwan playing a much more active, early, and central role in the narrative. Our memory of Moore’s Law has been reoriented.

But even without such obviously radical narrative ruptures and reorientations that raise or lower the status of contending charismatic entities, liveness defines entities rather than being defined by them. This is why it is a mistake to subordinate the former to the latter. “Players” appear live or not depending on how liveness is flowing or shifting course in their environments.

I just encountered a very clear example of this effect, in the just-concluded TV show Andor, which serves as a 2-season prequel to the movie Rogue One, which itself is a prequel to A New Hope. I think most Star Wars fans would agree that Andor is probably the best bit of storytelling in the extended universe. It is is the story with the most liveness.

I rewatched Rogue One again after finishing Andor, and was struck by how my response to the movie had been subtly but decisively altered by the show. When I first watched it, the character of Jyn Erso seemed like the protagonist and that of Andor Cassian like a sidekick. This time, the roles seemed reversed. That’s some powerful refactoring of perception, when a prequel genuinely alters how you view the thing it is a prequel to.

But the effect was deeper. In the larger Star Wars cosmology, Jyn is a character of almost-mythic proportions, a sort of minor member of the Skywalker tier of demigods, while Andor (like Din Djarin the Mandalorian) is a character of human proportions. One of the fascinating things about the evolution of the Star Wars is the gradual shift from mythic-scale to human-scale characters in the storytelling; from special people to strange rules. This seems to have really pumped up the liveness of the universe. The grander epic-arc movies seem curiously enervated now, once you’ve been immersed in the more intense liveness of the better TV shows. The epic-scale characters now almost seem like sideshow cartoons in the universe that was created for them. I need to update my old Epics vs. Lore thesis in light of this observation I think.

Anyway, the takeaway from that little Star Wars sidebar is that liveness is a property of a process — storytelling in this case — and as it flows and reflows, the apparent being-locked liveness of entities can change radically. Apparent live players can get flattened into cartoons, and vice-versa.

While in many cases, liveness and entity persistence coincide, constituting the “life” of an entity regarded as “alive,” the two are not the same, and the process condition is the more basic phenomenon. Indeed, the disembodied “phantom heads” of powerful leaders, as a client of mine once put it, can “haunt” organizations long after they are dead or departed, as the ghost of Steve Jobs still haunts Apple. This hauntological understanding of liveness is not vitalist. This sort of liveness can prosaically exist, distributed across many minds and processes, even if it is notionally associated with a single human. The Steve Jobs Process really is still live and running at Apple, because if never was co-extensive with the individual being of Steve Jobs. It was a vibe sentiment superstate covering the mutualist intersubjectivity of a largish sub-Dunbar cabal around Steve Jobs, with Jobs himself constituting only a small, if highly visible, part of it. The myth really was larger than the individual. Similarly, the Bezos process is still running at Amazon, even though he has departed. In both cases, the liveness is not at the level of the individual entities most obviously associated with it.

The classic exchange between Ducard (Liam Neeson) and Bruce Wayne (Christian Bale) in Batman Begins points to this idea in a rather on-the-nose way:

Henri Ducard: …A vigilante is just a man lost in the scramble for his own gratification. He can be destroyed, or locked up. But if you make yourself more than just a man, if you devote yourself to an ideal, and if they can't stop you, then you become something else entirely.

Bruce Wayne: Which is?

Henri Ducard: Legend, Mr. Wayne.

In fact, as I’ll argue, one test for liveness is the ability of a process to sustain a certain amount of observable and legible entity-hood within itself, but not too much. When the entity captures the liveness, the liveness dies. The process must ride the tension between being and becoming while resisting reduction to either. When that happens, living legends are born.

Observable and legible entity-hood is neither necessary, nor sufficient for liveness. In fact, even unobservable or illegible entity-hood is can be dispensed with. There need be nothing it is “like” to “be” a live process, for that process to be usefully considered live. The legend of Batman has liveness in both Bruce Wayne’s fictional universe and our own, but arguably there is nothing it is like to “be Batman” in either. There’s just Wayne in an imperfect mask-trance that is easily broken by a vast array of adversaries, actors who play a character snapping in and out of that mask-trance, and a fandom in our universe who treat the character as alive.

There are live processes that exhibit no outward signs or internal subjectivities of entity-hood, and processes that look like the coherent and life-like evolution of an entity from the outside, but lack liveness.

A good example of a process that exhibits liveness but is neither life-like, nor presents coherent entity-hood, is the one which first drew my attention to the concept — liveness in distributed computing. Specifically liveness in the sense of the Ethereum proof-of-stake system.

In this system, many decentralized nodes stake value (in the form of ETH), in order to validate transactions through a stake-weighted voting process. These stakes accrue rewards when nodes participate in valid transactions, and lose value (a process called “slashing”) if they participate in fraudulent transactions.

This system though, faces a practical issue. What if a node simply goes offline, due to being disconnected, or due to the computer crashing? How do you distinguish between a node that’s just offline for a bit, due to a recoverable crash or power outage, from one that has been destroyed in an earthquake?

Well, one way to accommodate such phenomenology is to design a “leak” into the system, where some of the stake is lost if a node isn’t participating enough in validating transactions. Eventually, if a node stays offline too long, enough of its stake leaks away that it carries too little weight in the validation process to matter. The node effectively leaks away its voting rights by not voting enough. The liveness routes itself around the deadness in guaranteed ways.

The interesting thing here is that while you could speak of nodes as being “alive” or “dead,” really it is the validation process that has liveness or deadness. If enough nodes die, the validation process itself dies. But like a Ship of Theseus (Flow of Theseus?), it doesn’t matter too much if the specific set of live nodes churns radically. There is no materially embodied entity-hood that is necessary for the process to be live, just as no particular actor is necessary for the Batman legend to be continued. The Ethereum validation process exhibits liveness, but there is nothing it is like to “be” that process.

You can find similar phenomena elsewhere. For example, voters may or may not vote in elections, and large segments of the population may become systematically active or inactive over time (often being charismatically reified in the process via archetypes like “hillbilly” or “welfare queen”), in response to the evolution of various issues. But it is most useful to speak of the democratic process being alive or dead, rather than particular voters, charismatic psychographic labels, or groups. Similarly, cells are born and die, and atoms flow through organic bodies, but the liveness of a biological entity is not attached to the materials that embody it at a given instant.

Indexicality at the Edge of Chaos

The old chaos/complexity theory tradition almost got to this sort of understanding and conceptualization of life and liveness. An important symptom of liveness is that the live process is on the boundary between order and chaos in some sense. But that conditions holds true for a lot of complex systems, from tornadoes to sand piles. These are sometimes interesting to consider as being alive in some poetic sense, but I’d like to get to a tighter sense of life and liveness that’s not quite so loose.

So what particular sorts of order and chaos are live processes poised between?

I will argue that liveness is the condition of a process poised between order and chaos in a way that it can recognize and respond to itself in its own memories, in the form of recurrent structures that are uniquely identifiable both in time and state (understood as a set of circumstances that cannot be trivially ordered in a directed way, and must therefore be understood as being concurrent). Think cycles and patterns if you like. Time-state crystalline structures. There are some parallels between my recognize/respond notion of self-reference and Douglas Hofstadter’s notion of a strange loop, but I’m aiming for a simpler, more usable account of similar phenomenology.

You will note that I’m rather awkwardly trying (and not entirely succeeding) to define and characterize things in pre-temporal ways here, because I want a notion of time to pop out of the idea of live processes, rather than pre-suppose one.

What does it mean for a process to recognize and respond to itself in its own memories?

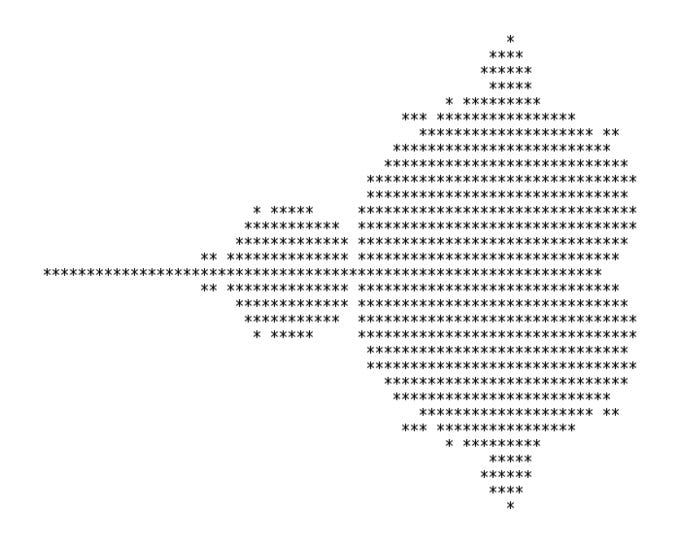

One illuminating edge case that falls just short of being an example is complex fractals like the Mandebrot set. The underlying equation (z=z²+c, where z is complex) that generates the iconic “ladybug” motif of the Mandebrot set is arguably an almost live process. The equation also defines a kind of time for the set. You can define time in terms of the order of a sequence of snapshot images tending towards greater resolution and complexity.

There is a recurring self-image in the recursion (the set as such can only be approximated through freeze-frame views of the recursion), even though the process itself likely cannot “recognize” itself in the evolving historical mirror it generates. The Mandelbrot set equation does not define a Turing-complete computation process, so it likely lacks the expressivity for such recognition and responsiveness, even though there is an element of “feedback” present. If you were to contaminate the computation with a noisy disturbance that threatens the coherence of the “ladybug,” the process would not in any sense attempt to resist the decoherence in memory-preserving ways, the way a true live process would. At least this is what I suspect. I haven’t tried the experiment.

What resistance or homeostatic stability there is would be more like the resistance of a rock to being shattered or eroded, an artifact of the underlying physics rather than any kind of liveness or memory-stabilizing tendency.

I got to thinking about memory in this way thanks to Kei Kreutler’s essay, Artificial Memory and Orienting Infinity. Liveness is a special case of memory-as-orientation that we might call indexical orientation; an orientation that creates a proto-identity or point-of-view of sorts. In linguistics, an indexical statement is one whose meaning depends on who speaks it and what they’re referring to, like “this one is mine.” That statement could mean “that pen is Venkat’s” if I say it, pointing at my pen, or something else in non-indexical terms if someone else says it.

But you don’t need entity-hood for indexicality, only an oriented memory. The meaning of a statement depends on the oriented memory it is situated within. This definition of an indexical memory orientation, of course, is partly motivated by how memory context works in LLMs. The identity that constitutes liveness need not be inhabitable or conscious. ChatGPT’s side of a conversation for example, is orientable memory that can plausibly function as an identity and emulate personhood, but is currently neither inhabited, nor inhabitable in principle, in my opinion. Nor do I think it is conscious in any sense of the word. There is currently nothing it is like to be holding up ChatGPT’s end of a conversation.

More obviously, there is nothing it is “like” to be a Trump or Kamala voter in the abstract. Both voter archetypes can be understood as oriented memories of political events and futures, which can coherently sustain indexical statements. Making a statement like Trump voters want X is as dangerous and seductive as making a statement like ChatGPT believes X. In fact, the two phenomena are similar, since ChatGPT is trained on actual human data. Political archetypes are in some ways artisanal approximations of LLMs. You could train a model to represent “Trump voter.”

Such evolving oriented memories may not be inhabited or inhabitable, but they do exhibit liveness. Not a very stable sort of liveness, but one that definitely feels more alive than dead. A different flavor of computational liveness than that exhibited by the validation process of Ethereum, but there is a familial relatedness there. ChatGPT will resist the conversation being derailed by non sequiturs and strive mightily to connect the dots. Ethereum blockchain validation will resist being derailed by offline nodes and strive mightily to keep the transaction flow going. Casting a wider net, the legends of Batman, Steve Jobs, or “Trump voter” will resist profane treatments of the respective superhero characters and strive mightily to keep the evolution of the canons true to the underlying archetypes.

So for a process to exhibit liveness, the associated memory needs to be orientable in a particular way. It must exhibit evidence of an orientation-preserving relationship to its historical trajectory based and recognition and responsiveness. A kind of homeostatic information inertia or process “grain.” The metaphor of a grain is useful here. Both wood and rocks exhibit a grain, but a living tree has more liveness than either dead wood or rocks, because it resists alteration in a more actively opinionated, memory-preserving way. A tree is embodied and indexically oriented (but arguably uninhabited and uninhabitable) evolving memory that resists disruption. A rock or a piece of wood is not. Or at least not to the same degree. They have less liveness.

But if the proto-identity of liveness happens to be inhabitable, arguably we arrive at one of the preconditions of conscious life, of the sort we are typically willing to consensually attribute to any animal life more complex than an oyster. Intelligence is arguably another independent process dimension predicated on liveness (but not on consciousness). Live, conscious, and intelligent are, in this scheme, orthornormal dimensions of certain process conditions that are closest to “human,” in order of ontological priority.2

For the purposes of this essay series, I’m only interested in liveness (and obliquely, in bugs, and haunting).

Liveness, consciousness, and intelligence frequently occur together, but I see no necessary reason why we cannot have processes that feature only one or two of the three, so long as liveness is in the set. In particular liveness alone, or liveness and intelligence, seem equally capable of being either machinic or organic. A live intelligence that is organic but not conscious might seem strange, but that’s only if you think in anthropocentric terms about p-zombies. I can imagine, for instance, a live and intelligent mycelial network that doesn’t quite so strongly suggest consciousness.

All four process conditions that include liveness ( (count ‘em), I think, satisfy the condition of being reducible to indexically orientable memory processes poised between order and chaos.

What does that mean? It means liveness involves memories oriented in ways that are clock-like.

Liveness and Time

Liveness is the entangled emergence of memory and time. A rock has a history, exists in chronological time, and might embody a record of that existence. But arguably that record isn’t memory, it is merely memory-like. A live process must “read-in” and “digest” that record, and reorient in response to it, without losing its own liveness in the process, for it to become memory.

Harmonizable records might nourish the liveness of a process. Hostile ones might poison and kill it.

Liveness in a process requires constant consumption and excretion of information, which is a risky process that both sustains and threatens. Usually, liveness feeds on like kinds of liveness. Photosynthesis is a rare process that can be viewed as either creating liveness from non-liveness, or liveness from a different sort of liveness (depending on what you think solar radiation and element cycles on earth represent).

When liveness succeeds in sustaining itself, memory and time emerge together.

Here we can return to our running machinic example of elemental liveness. A pendulum clock exhibits a certain liveness in the stability of its oscillations that persist and resist derailment despite the second law of thermodynamics. This stability rides the tension between a generative force (the unwinding mainspring) and a dynamic constraint (the escapement). There is an evolving memory of tick-tock oscillations (which isn’t usually recorded, but easily could be) that is orientable (the noise level gradually increases and the oscillation destabilizes as the spring unwinds), and resists disruption.

Whether we are talking about clocks, blockchains, LLMs, trees, Batman, hauntological “Steve Jobs,” or literal humans, the past is precisely that subset of available memory in which the live process can recognize and respond to itself, whether or not it harbors consciousness or intelligence. The future is precisely that subset in which such recognition is unstable or unraveling, ordered by the manner of the unraveling.

Such unraveling can unfold both sequentially (inducing “forwards” and “backwards” directions of time), and laterally (“sideways” in time, into the adjacent possible, marked by ordering ambiguities such as forks).

Note that this informational understanding of past and future does not rest on a cleaving of past and future by means of a point-like “present,” on a Cartesian line. Nor is it interchangeable with it.

In this liveness-defined sense of memory and time, the “present” comprises memories that resist natural sequencing and ordering (the idea of state as order-resistant concurrency I introduced earlier), and partition other memories into two disjoint sets that exhibit distinguishable patterns of stability and unraveling.

Conventionally, we understand this in terms of a highly stable and certain set of memories (the “past”), and a highly unstable and contingent set of memories (the “future”). We experience a psychological arrow of time that points from the “past” to the “future” in a one-dimensional way that correlates with the chronological arrow of time, but is not identical to it. The “sideways” direction of time into the adjacent possible seems less viscerally real, but as I’ll argue in a future post, it’s more real than you might think. It is possible to “thicken” your sense of time to include it.

Expectations that are notionally a part of the chronological future may in fact be psychologically part of the past. Understandings of elements of the chronological past that are highly unstable and contingent may in fact be part of the psychological future.

So far, this is not a radical theory of time. What makes it radical is dispensing with the chronological understanding of time entirely, and treating it as a projective fiction that emerges from the psychological experience of time. I want to put this out there for your consideration, but won’t delve into it (you can read Carlo Rovelli’s books on contemporary physics understandings of time if you are interested, and Greg Egan’s novel Permutation City for a mind-churning and not entirely coherent exploration). I won’t need to discard chronological time for my purposes, but I want to make the point that it is not necessarily more “fundamental” or more of a “ground truth” than psychological time.

Moreover, these are not esoteric concerns. Subjective time can quite literally collapse under stress, like in a Christopher Nolan movie, and this is at the root of many kinds of trauma. I will discuss this in a future essay.

Though the two understandings of time aren’t the same, they do tend to line up in contemporary experience, and such lining up might even be the best definition of “normalcy.” We experience aligned arrows of psychological and chronological time that point together from memories in the clock-past towards expectations in the clock-future. The two arrows seem to orbit each other as the liveness unfolds and memory and time create each other. And at least the psychological arrow seems to rest on liveness as a precondition.

But this may not always have been the case. In the next part, I’ll look at liveness in historical processes and how the historical arrow of time may have become “fixed” by print, injecting liveness into the historical process of Europe at the cost of alienating it from its own history.

I’m thinking of the concepts of readiness to hand, readiness at hand, and unreadiness at hand. Heidegger seems to be one common jumping off point for contemporary continental philosophers investigating technology, such as Yuk Hui or Byung-Chul Han. I am fundamentally wary of this tack.

Liveness plus consciousness, with or without intelligence, still seems inscrutable to me, and I’m inclined to think (though less strongly than I once did) that this combination can only occur in organic forms. Consciousness and/or intelligence, sans liveness, are strange immanent categories that I think cannot exist in organic form (ie organic life must tautologically exhibit liveness by definition, but I mean that in a deeper sense), but perhaps might in machinic form. Older LLMs with no saved memories could be considered intelligences without liveness. Consciousness without liveness seems like an ill-posed category to me, and I can’t make up a plausible organic or machinic hypothetical that fits.

Seems to me the connection of all three is autopooeisis.

This notion of liveness feels very much in line with the Karl Friston gang's work on active inference and the free energy principle