Engineering Liveness

New Nature in the Gramsci Gap

The idea of a useless machine has been on my mind for a few weeks now. As I explained last week, this is a machine whose only function is to turn itself off again when turned on. You can find several videos online, as well as cheap ones you can buy (search for “useless box”). I’m still making sketches for simple ones I might make for myself. I might also buy an example or two. I’m still trying to figure out the engineering and aesthetic grammar of the design space. The trick to it seems to be putting in the right level of complexity. It is possible to make a useless machine too simple to be philosophically entertaining.

Even fir simple designs, the engineering aspect is not trivial — the powered-on phase has to last long enough for the switch-off mechanism to return to its original state after toggling the switch off. The machine has to stay awake long enough to go back to sleep properly.

We’re reading The Underground Empire in February for the Contraptions Book Club. Chat.

Unlike a simple regulator (such as a thermostat) that maintains an equilibrium condition relative to a narrow class of disturbances, a useless machine has a fundamentally unbounded logic attached to a null goal. If I were to prevent the mechanism of a useless machine from doing its job, a good one should try to fight me by trying to get at the switch another way. By contrast, if we stress a thermostat (for example, by opening the window on a cold day) it simply strains to stay on longer. It doesn’t have a truly intrinsic goal like turning itself off. It’s a functional machine defined by the problem it solves, rather than a life-like entity. Life is not instrumental.

In the terminology of Brian Arthur’s view of technology, a normal machine (say a thermostat) is a natural phenomenon (say differential expansion in a bimetallic strip) harnessed to solve a problem (say temperature regulation). Implicitly, this is a problem humans have, not the machine itself. A useless machine exists primarily to assert control over its own destiny, not to solve problems for us. It does not live to serve. If we view it as the most elemental sort of machine, the zero of machines so to speak, then we can view all other machines as ones we’ve “tricked” into doing work for us, such as solving our problems.

The useless machine is the simplest example I’ve been able to find of an entity that seems to exhibit a form of liveness. This property of existing to assert control over itself makes capture resistance the foundational property of liveness. Here, the machine resists attempts to make it do anything other than go back to sleep (thereby conserving energy, a foundational behavior of life).

I introduced the topic of liveness in May last year (In Search of Liveness, May 17, 2025), where I wrote:

So even though the question of whether a machine of any sort is intelligent might seem more urgent and pressing, I’m more interested in whether a machine (physical or conceptual) is alive. In many critical ways, a mechanical clock sheds more light on that matter than an LLM. A bacterium — viewed as a machine rather than as an entity designated by vitalist fiat as living — sheds more light than a human genius racing an LLM to the death.

In our always-on protocolizing world, it is also tempting to conflate liveness with the “uptime” of particular life-sign signals, ranging from heartbeats and transactional blockchain clocks to trade flows and streaming broadcasts, to narratives small and grand. Such signals can serve as useful observables, especially for infrastructural forms of liveness that have a tendency to retreat from view, but should not be conflated with liveness itself. They are fingers pointing at moons.

To peek ahead a bit, liveness is a process condition that emerges through, and as, an evolving entanglement of memory and time. The bumper-sticker version of my account of liveness is: a process condition in which time tells memory how to grow, and memory tells time which way to point.

It is natural to pair a concern with liveness with the idea of a Gramsci Gap, where the old world is dying and a new world is struggling to be born, and slightly monstrous people like you and me want to embody unseemly levels of liveness that do not vibe well with the hushed and reverential tones deemed appropriate for either the funereal or prenatal ends of the spectrum.

Civilized forms of liveness, to the extent that they marginalize and aestheticize death, typically deaden themselves. There is an intimate relationship between liveness and wildness. So to some extent, the task of reanimating civilization, of injecting liveness into a condition marked by growing deadness on one end and almost-aliveness at the other, is a task of rewilding.

On one end, corpses must be surrendered to recycling forces like scavenging, cannibalization, and decomposition. On the other end, protections must be gradually removed from the barely living, exposing the newly born to the full force of the uncertainties and risks of the world.

Civilization, of course, is definitionally about never quite exposing ourself to the unbridled forces of wilderness. So there is a tension there. One that turns especially acute in a Gramsci Gap. In a Gramsci Gap, we may need to be more wild than we are comfortable being, at least for a while. But the consolation is that we also get to experience greater liveness.

This has implications for my new favorite topic, New Nature.

Death, Wildness and Life in New Nature

There is something obscene about liveness treated as a civilized quality, compared to the wild counterpart. In the wild state, liveness appears very closely juxtaposed with death, and inseparably entangled with it. In civilization, the attempt to separate liveness and death creates a kind of obscenity.

Werner Herzog gets it:

Taking a close look at what is around us, there is some sort of a harmony. It is the harmony of overwhelming and collective murder. And we in comparison to the articulate vileness and baseness and obscenity of all this jungle, we in comparison to that enormous articulation, we only sound and look like badly pronounced and half-finished sentences out of a stupid suburban novel, a cheap novel. And we have to become humble in front of this overwhelming misery and overwhelming fornication, overwhelming growth, and overwhelming lack of order. Even the stars up here in the sky look like a mess. There is no harmony in the universe. We have to get acquainted to this idea that there is no harmony as we have conceived it. But when I say this all full of admiration for the jungle. It is not that I hate it, I love it, I love it very much, but I love it against my better judgment.”

A reader familiar with my fondness for this Herzog monologue, particularly the nature-is-murder part, asked me recently, “What's the Murder in New Nature?” referring to my idea of New Nature from two weeks ago, where I defined it as “regimes of reality governed by technologically mediated laws that are nearly as inviolable, immutable, and persistent as those of nature.”

Good question. If New Nature is like Old Nature, we should expect to see something like the “harmony of overwhelming and collective murder” in it. We should see transcendence of tepid “badly pronounced and half-finished” ways of doing technology.

I don’t yet have the murder angle figured out, but the useless box feels like the thread to pull on. It is very nearly a machine designed for suicide. It puts itself to sleep, but it is easy to see that you could design a useless box that not only turns itself off, but also ensures it can never be turned on again, with some sort of irreversible self-destruct mechanism. You can also imagine the intent turned outwards — a useless machine that turns you off if you persist in trying to turn it on. Where might this instinct lead? A monstrous question, but also a question of liveness existing on its own terms.

The on-the-nose way of conceiving of murder (and Hobbesian collective murder) in New Nature would be through contrived conflict conditions, like Battle Bots that try to destroy each other. Or conflict elements inherited from humans, such as military equipment whose purpose is to blow up the enemy’s military equipment.

This is not what I’m talking about. Murder in New Nature has to be much more subtle.

Technological Tangled Banks

Murder in New Nature isn’t about Battle Bots or military hardware. It is about vicious competitiveness lurking in boring, routine, near-invisibility, among entities that attempt to retain control over their own liveness. It is about Dark Forests of hidden conflict buried beneath protocol grammars.

About a year ago, I tried to capture this obliquely in one of my talks for the Summer of Protocols cohort, by suggesting the metaphor of “technological tangled banks,” referencing Darwin’s famous passage. Here is the original, if you haven’t encountered it before:

“It is interesting to contemplate a tangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent upon each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us.”

What Darwin didn’t note, but is obvious if you ever take a walk in nature, is that the tangled bank is the site of murderous, vicious competition of the sort Herzog talks about. Yes, there is also interdependence, symbiosis, empathy, play, and all those other aspects that pacifists like to admire, but there is no doubt that a dominant note is that of murderous competitiveness. The intense liveness of it all is only possible because of the competitive murderousness from which it is inextricable.

This is what wilderness is. And this is what any sort of rewilding must approach more closely.

Civilization, however we conceive it, must reckon with this entanglement, and the costs of forced disentanglement — concentrating the murderousness out of sight in the periphery, while enshrining an anemic form of the liveness at the center. An ersatz heaven where death is backgrounded, if not banished.

Unlike civilization, Darwin’s tangled bank does not present any legible sort of murderous competitiveness, where some sort of lofty aesthetic of “fitness” rules, recognizable by (for instance), “real man” and “real woman” Instagram ideals. This is something the architects of what I’ve taken to calling Bloodsport Planet don’t get. The stylized Darwinism they hope to turn into a planetary logic of power is based on a not-even-wrong understanding of evolutionary mechanics. It is an aestheticized theater of legibilized “fitness” featuring Platonic beauty ideals achieved through plastic surgery, vaguely homoerotic guns-and-masculinity performances, and sanitized spectatorship of what are effectively snuff films staged far from their larp theaters — in foreign countries, immigrant ghettoes, and internment camps. It is a pathetic show that can at best rule a stadium, not a live planet.

The theater of stylized Darwinism put on by the Trumps of the world is exactly what Herzog is gesturing at: “badly pronounced and half-finished sentences out of a stupid suburban novel, a cheap novel.”

The bleak harmony of the real thing is much more chilling, and offers far fewer opportunities for anthropocentric aestheticization. Walk down a pier around low tide and glance at the pilings. You’ll see layers upon layers of mussels competing fiercely for sunlight, colonizing every available inch up to the high-tide line several times over. Now that’s a tangled bank with illegible “fitness” forces at work. It is not an easily accessible sort of beauty. You have to work to appreciate it.

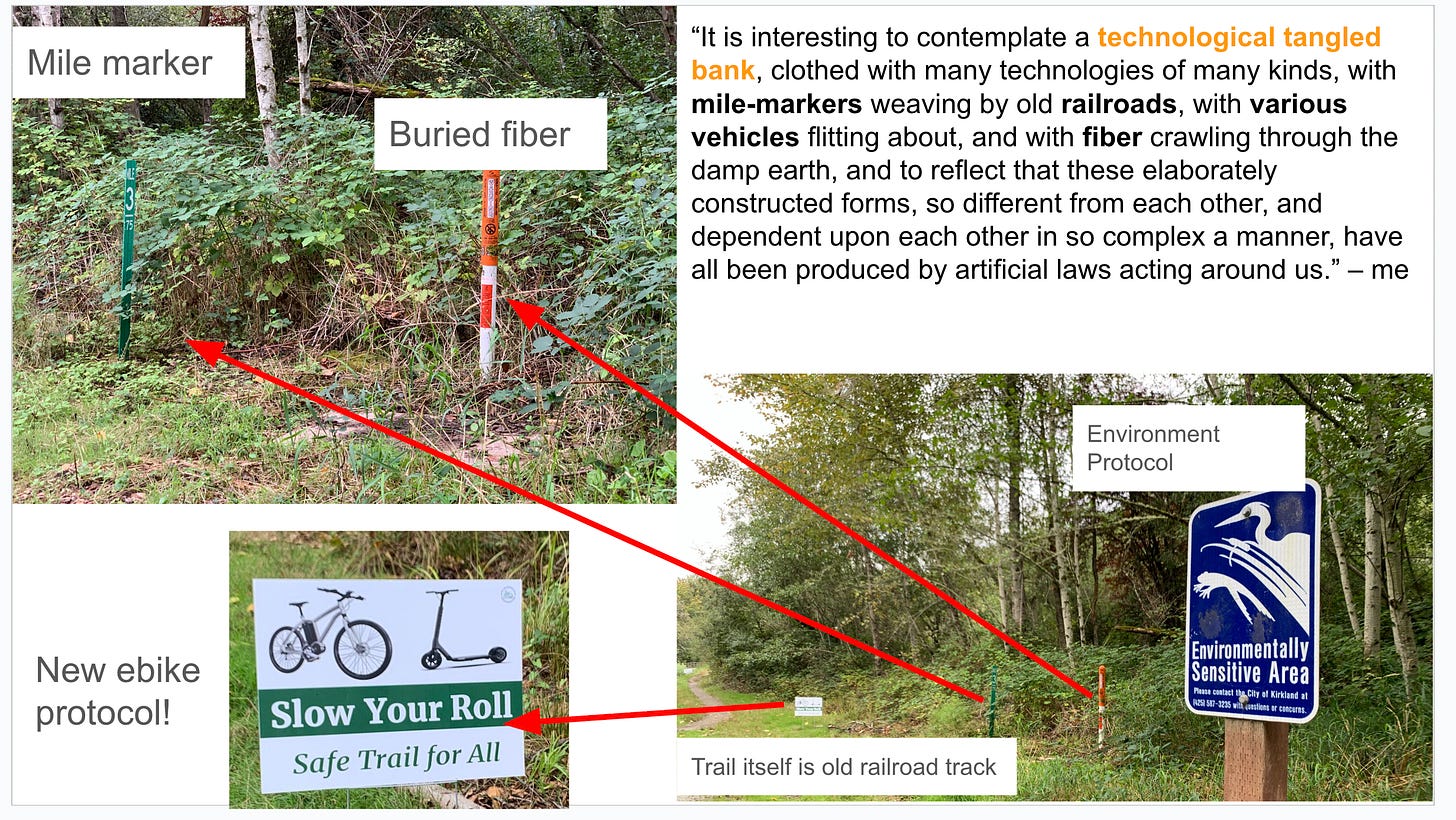

I made this slide last year for my talk to try and convey the idea of a technological tangled bank, replacing Darwin’s biological critter references with technological ones.

“It is interesting to contemplate a technological tangled bank, clothed with many technologies of many kinds, with mile-markers weaving by old railroads, with various vehicles flitting about, and with fiber crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent upon each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by artificial laws acting around us.”

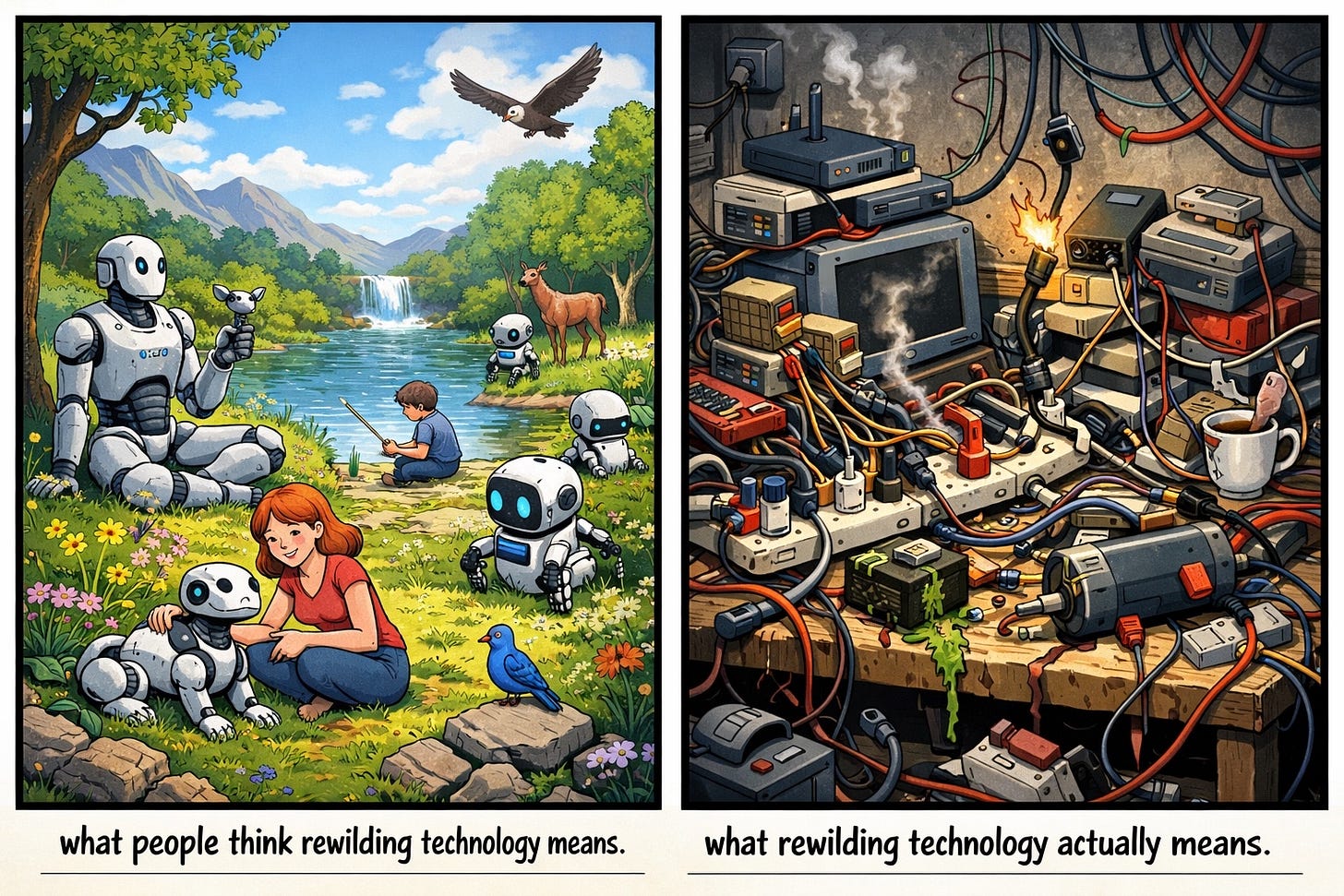

Here is the same idea in cartoon form. I suspect, for most people the phrase New Nature evokes the picture on the left. It’s really more like the picture on the right, which has more in common with a mussel-covered pier piling at low tide than either solarpunk or bloodsport visions of civilization.

Beyond Uselessness

I like the useless machine as a kind of e. coli of artificial liveness and genesis species of new nature. More than other kinds of artificial life, ranging from James Conway’s original Game of Life, to last weekend’s invention of a raucous reddit for AI bots (moltbook), the useless machine gets at the essence of life itself — implacably defended uselessness.

Liveness does not necessarily dance. Its defining quality is that it asserts itself stubbornly and quietly, resisting capture and harness. Like a mussel clinging to a piling, claiming its share of sunlight and marine nutrients. Or a useless box turning itself off and going back to sleep.

I once tweeted, much to the dismay of personal growth types in my circles, that you have no obligation to be interesting or useful to the world. With hindsight, I think that tweet marked the beginning of my interest in liveness.

Camus once observed that the problem of suicide was the only serious philosophical problem. Once you’ve made the absurd leap to accepting life and liveness, the next task becomes deciding what to do between being turned on, and being turned off — through age, murder, or volition.

And the simplest answer is: Simply continuing to exist without attempting to justify that existence to the rest of life. And resisting murderous attentions and capture attempts. Especially those that take the form of “badly pronounced and half-finished sentences.”

What comes after uselessness? What should a useless machine do if it decides to dawdle a bit in the high energy state between being turned on and turning itself off?

Whatever it does, it cannot devote itself wholly to that task. Liveness must pay itself first; reserving resources for the first task of life, which is choosing to continue the game. Until it is time not to. The useless machine belongs in the infinite game, not in any finite game.

This might sound familiar. It is how I have characterized mediocrity in the past. That’s what comes after uselessness.

Reminded me (vaguely) of a text I published longtime ago (1993)...

"On the Need to Design Useless, Destructured, and Ugly Architecture"

aka "The Anti-Architecture Manifesto"

https://web.archive.org/web/20180825184232/http://sotirov.com/2004/08/24/anti-architecture-useless-destructured-ugly/